Post-Op Follow-Up Schedule That Prevents Prosthetic Delays (For Clinicians)

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

Cancer-related amputation is not just a surgical event. It is a long and complex journey that affects the body, the mind, and the sense of identity. For many patients, the question is not only whether a prosthetic can be used, but when it is medically safe, physically possible, and emotionally right to do so. Timing matters as much as technology in oncology-related prosthetic care.

At Robobionics, we have worked with patients who have lost limbs due to bone tumors, soft tissue cancers, infections following cancer treatment, and complex surgical decisions made to save life. Each case is different. Recovery is shaped by wound healing, cancer treatment cycles, energy levels, pain, and long-term health goals. A prosthetic fitted too early can cause harm. A prosthetic delayed too long can reduce confidence and function.

This article focuses on one critical question: when is prosthetic fitting clinically appropriate after oncology-related amputation. It explains how healing, cancer status, strength, and overall stability guide safe timing. It also highlights how realistic planning can protect outcomes and improve quality of life. The goal is not speed, but readiness.

If you are a patient, caregiver, or clinician navigating life after cancer-related limb loss, this guide is meant to offer clarity. Prosthetic fitting is not a race. When done at the right time, with the right preparation, it can support recovery, independence, and long-term well-being.

Oncology-related amputation is usually a life-saving decision.

It is considered when cancer cannot be fully removed while saving the limb.

This is common in aggressive bone tumors and some soft tissue cancers.

In some cases, infection or poor healing after cancer treatment forces amputation.

Radiation and chemotherapy can weaken tissues and blood supply.

This makes limb preservation unsafe or impossible.

The reason for amputation strongly affects prosthetic planning.

Cancer type, spread, and treatment history all matter.

These factors shape recovery speed and long-term readiness.

Cancer-related amputations are planned surgeries, not sudden events.

The body often enters surgery already tired from treatment.

Healing tends to be slower and more complex.

Unlike trauma cases, tissues may be fragile.

Scarring, radiation damage, and reduced immunity are common.

This affects socket tolerance and fitting timelines.

Because of this, prosthetic fitting must be more cautious.

Clinical readiness matters more than emotional urgency.

A slower approach often leads to better outcomes.

Cancer already places a heavy emotional load on patients.

Amputation adds another layer of loss and fear.

Many patients feel overwhelmed rather than rushed.

Some patients want a prosthetic immediately to feel whole again.

Others need time to process survival and body change.

Both responses are valid and must be respected.

Psychological readiness is part of clinical readiness.

A patient who feels pressured may struggle with training.

Emotional stability supports safer and more consistent use.

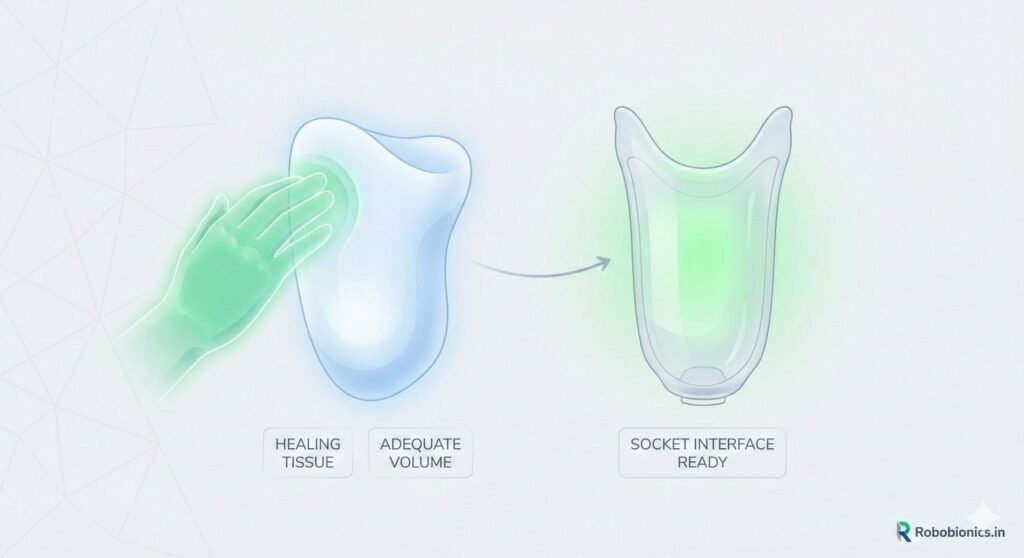

Prosthetic fitting cannot begin until healing is stable.

The surgical wound must be fully closed and dry.

Any drainage or open area delays fitting.

Cancer patients may heal slower due to treatment effects.

Chemotherapy and radiation reduce tissue repair ability.

This requires patience and close monitoring.

Rushing fitting before healing increases infection risk.

It can also damage delicate tissue.

Healing always comes before mobility goals.

Swelling is common after amputation.

In oncology patients, it may last longer.

Radiation can worsen fluid retention.

A stable limb shape is needed for prosthetic fitting.

Ongoing swelling leads to poor socket fit.

This causes pain and skin breakdown.

Compression therapy is often used early.

It helps shape the limb gradually.

This prepares the body for safe prosthetic use.

Cancer surgeries often leave large scars.

Radiation can make skin stiff or fragile.

These changes affect socket comfort.

Sensitive scars may react poorly to pressure.

Pain can limit prosthetic tolerance.

Desensitization may be needed before fitting.

Assessing scar flexibility is essential.

Good tissue movement improves comfort.

Poor scar quality often delays prosthetic readiness.

Prosthetic fitting is usually delayed during active treatment.

Chemotherapy causes fatigue, weakness, and nausea.

Radiation can cause skin breakdown.

During this phase, the body needs rest.

Adding prosthetic training increases physical stress.

This may slow overall recovery.

Temporary mobility aids are often safer.

Wheelchairs or walkers support function.

Prosthetic fitting waits until stability improves.

After treatment ends, the body slowly regains strength.

Blood counts stabilize and energy improves.

This is often the window for prosthetic planning.

However, follow-up scans and reviews continue.

Cancer recurrence risk must be considered.

Prosthetic plans should remain flexible.

Clinical clearance from oncology teams is important.

This ensures medical safety.

Team coordination improves outcomes.

In cases of advanced cancer, goals may differ.

Prosthetic fitting may focus on comfort, not performance.

Short-term function may be the priority.

Life expectancy influences prosthetic complexity.

Simpler devices reduce training burden.

They support quality of life without excess strain.

Honest discussions are essential.

Patients deserve realistic options.

Prosthetics should support meaningful living, not exhaustion.

Cancer treatment reduces muscle strength.

Fatigue is one of the most common complaints.

This affects prosthetic training capacity.

Patients must have enough strength to stand and balance.

Core and hip muscles are especially important.

Without them, prosthetic use becomes unsafe.

Readiness is assessed through simple tasks.

Standing endurance reveals a lot.

Energy consistency matters more than peak strength.

Cancer and its treatments affect balance.

Nerve damage, weakness, and dizziness are common.

These increase fall risk.

A prosthetic changes balance demands further.

The body must relearn weight shifting.

This requires good coordination.

Balance testing helps guide timing.

Poor balance suggests delay or simpler devices.

Safety always comes first.

Pain is common after cancer surgery.

Phantom pain and residual limb pain may persist.

Uncontrolled pain blocks prosthetic success.

A patient in pain cannot train well.

Movement becomes guarded and unsafe.

This increases injury risk.

Pain should be reasonably controlled before fitting.

Not eliminated, but manageable.

Comfort supports learning and confidence.

Cancer patients may have reduced immunity.

This increases infection risk.

Skin integrity becomes critical.

Prosthetic sockets apply constant pressure.

Weak skin breaks down easily.

This leads to wounds and delays.

Skin must be healthy and resilient.

Minor irritation should heal quickly.

This is a key readiness marker.

Bone quality may be affected by cancer.

Tumors, radiation, and medication weaken bones.

This impacts load-bearing ability.

Poor bone strength limits prosthetic use.

Stress fractures are a risk.

This is especially relevant in lower limb cases.

Imaging and medical review guide decisions.

Load must match bone capacity.

Safety overrides ambition.

Nerve damage is common in oncology cases.

This reduces sensation in the residual limb.

Patients may not feel pressure or injury.

Reduced sensation increases skin risk.

Damage may go unnoticed.

This requires extra caution.

Socket design and fit become crucial.

Frequent skin checks are essential.

Patient education is non-negotiable.

Prosthetic use requires focus and effort.

Patients must be mentally ready to learn.

Cancer recovery can cloud concentration.

Depression and anxiety are common.

These affect motivation and follow-through.

Ignoring them leads to poor outcomes.

Mental readiness should be assessed openly.

Support may be needed first.

A stable mind supports a safe body.

Cancer survivors often hope for normal life.

This is natural and understandable.

However, expectations must match reality.

Prosthetics restore function, not perfection.

Energy levels may remain lower.

Pacing becomes important.

Clear expectation setting prevents disappointment.

It builds long-term satisfaction.

Honesty is a form of care.

Families often push for quick prosthetic fitting.

They want visible recovery signs.

This can pressure patients.

Such pressure may backfire.

Early failure reduces confidence.

The patient may withdraw.

Including families in education helps.

Understanding readiness criteria reduces stress.

Support becomes more aligned.

Waiting for prosthetic readiness does not mean inactivity.

Temporary mobility is essential.

It prevents deconditioning and isolation.

Wheelchairs, crutches, or walkers are commonly used.

They support independence during healing.

They also reduce fall risk.

These tools are not failures.

They are part of recovery.

They protect long-term outcomes.

Muscle loss happens quickly after amputation.

Cancer accelerates this process.

Early conditioning is important.

Physiotherapy focuses on safe exercises.

Core strength and transfers are key.

This prepares the body for prosthetics later.

Gentle activity supports circulation and mood.

It also improves healing.

Preparation shortens future training time.

Waiting can be emotionally hard.

Patients may feel stuck or left behind.

Clear communication reduces distress.

Explaining the reason for delay helps.

Patients need to know it is protective, not neglect.

Trust grows through transparency.

Emotional support during this phase matters.

It shapes long-term engagement.

Patience becomes easier with understanding.

Prosthetic fitting becomes appropriate when several signs align.

The wound is healed and stable.

Swelling is controlled and limb shape is consistent.

Pain is manageable and skin is healthy.

Strength and balance meet minimum safety levels.

Cancer treatment is stable or completed.

No single factor decides readiness.

It is a combined judgment.

Team consensus improves safety.

Initial fitting is often a trial.

It tests tolerance, not performance.

Short wear times are used.

Gradual exposure protects the limb.

The body adapts step by step.

This reduces injury and fear.

Feedback during this phase is critical.

Adjustments are expected.

Flexibility leads to success.

Readiness does not end at fitting.

The first few weeks are crucial.

Issues often appear during real-world use.

Skin, pain, and fatigue must be monitored.

Cancer survivors may fluctuate day to day.

Plans must adapt.

Regular follow-up prevents setbacks.

Early correction saves time and health.

Prosthetic care is an ongoing process.

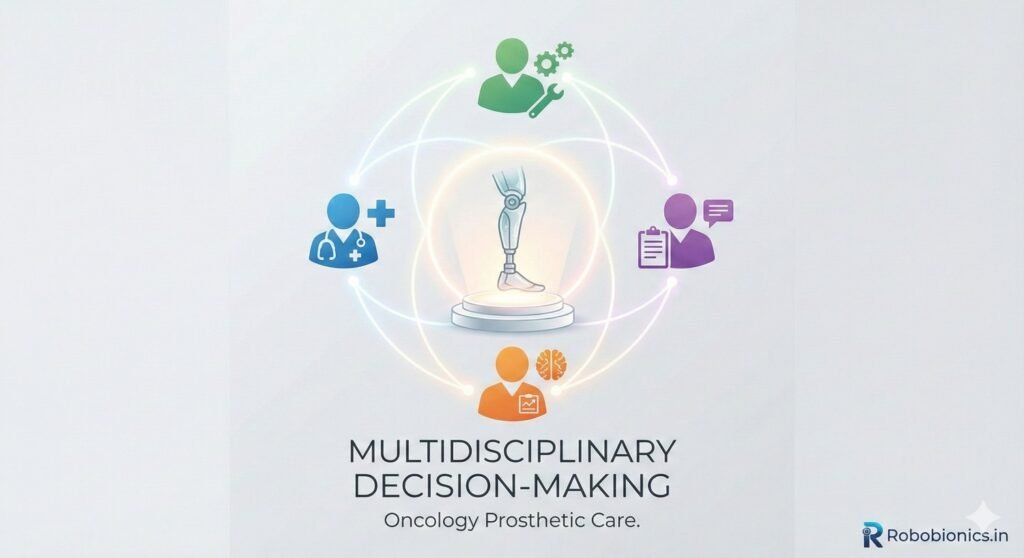

Prosthetic fitting after cancer-related amputation should never be decided in isolation, because the oncology team has critical insight into disease status, treatment effects, and future medical plans that directly influence safety and readiness. Oncologists understand whether the cancer is stable, whether additional treatment is planned, and how the patient’s body is expected to respond over time, all of which affect prosthetic tolerance.

Close communication with the oncology team helps prevent situations where a prosthetic is fitted just before a new chemotherapy cycle or radiation phase, which could suddenly reduce skin tolerance, energy levels, or immunity. When prosthetic planning aligns with oncology timelines, complications reduce significantly and patient confidence improves. This coordination ensures that mobility goals support, rather than interfere with, cancer recovery.

Prosthetists and rehabilitation specialists play a central role in translating medical readiness into functional reality, because they assess how the body moves, reacts to load, and adapts to new patterns after amputation. In oncology cases, these professionals must be especially attentive to subtle signs of fatigue, pain, or tissue stress that may not appear during brief clinic visits.

Collaboration allows prosthetic design, alignment, and training plans to evolve together rather than being fixed decisions. Rehabilitation feedback helps prosthetists refine socket design and suspension methods, while prosthetic adjustments allow therapists to progress training safely. This continuous loop of communication creates a safer and more responsive care pathway for cancer survivors.

One of the most overlooked aspects of multidisciplinary care is consistent communication with the patient, because mixed messages about readiness or expectations can create confusion and emotional distress. When all team members share a common understanding of why prosthetic fitting is delayed or initiated, patients feel reassured rather than discouraged.

Unified messaging helps patients trust the process even when progress feels slow. It reinforces the idea that timing decisions are protective rather than restrictive. This trust directly influences engagement with rehabilitation and long-term prosthetic use.

In oncology-related amputations, simpler prosthetic designs are often more appropriate, especially during early fitting phases, because the body may still be adapting to post-treatment changes. Simpler systems reduce cognitive and physical load, making it easier for patients to focus on safe movement rather than device management.

This does not mean limiting future potential, but rather building a stable foundation first. Many cancer survivors benefit from starting with basic components that emphasize stability and comfort, with the option to upgrade later if strength, confidence, and health improve. This staged approach protects early outcomes and reduces the risk of abandonment.

Cancer recovery is rarely linear, and prosthetic goals must reflect this reality to remain achievable and meaningful. Some patients regain strength steadily, while others experience plateaus or setbacks due to late treatment effects or unrelated health issues. Prosthetic planning must remain flexible enough to adapt without framing these changes as failures.

For some individuals, the primary goal may be safe indoor mobility, while for others it may be limited outdoor walking or return to specific daily roles. Aligning prosthetic goals with current recovery status ensures that effort invested in training leads to tangible improvements in daily life rather than constant frustration.

Energy conservation is a major concern in oncology survivors, because fatigue can persist long after treatment ends. Prosthetic designs that demand excessive effort may technically work but leave patients exhausted, reducing overall quality of life. Selecting components that support efficient movement and minimize unnecessary strain is therefore essential.

Long-term success depends not on how much a patient can do on their best day, but on what they can do consistently without worsening fatigue or pain. Prosthetic choices should support sustainable mobility rather than peak performance, especially in individuals with ongoing cancer-related health considerations.

One of the most serious risks of early prosthetic fitting in oncology patients is wound breakdown, because cancer treatments often compromise skin strength and immune response. Even small areas of pressure or friction can reopen healing wounds, creating entry points for infection that may be difficult to control.

Infections in cancer survivors can escalate quickly and may interrupt ongoing treatment or recovery plans. Delaying prosthetic fitting until tissue resilience is clearly established reduces this risk significantly. Protecting healing tissues must always take priority over early mobility gains.

Early fitting when the body is not ready often leads to repeated discomfort, instability, or failure during training sessions, which can teach the patient to associate the prosthetic with fear or pain. These negative learning experiences are difficult to reverse and may lead to long-term avoidance of the device.

Confidence is especially fragile after cancer-related amputation, because patients are already coping with physical and emotional exhaustion. Introducing a prosthetic at the wrong time can reinforce feelings of limitation rather than empowerment. Proper timing helps ensure that early experiences are positive and confidence-building.

Falls are a major concern in oncology patients, particularly when balance, strength, or sensation is compromised. Early prosthetic use without adequate readiness increases fall risk, which can result in fractures, head injury, or setbacks that delay overall recovery.

A single fall can dramatically change a patient’s willingness to engage in rehabilitation. Preventing this outcome requires patience and careful readiness assessment. Waiting until balance and strength reach safe thresholds protects both physical health and emotional resilience.

When prosthetic fitting is timed appropriately, patients experience better socket comfort because swelling has stabilized, scars have matured, and skin tolerance has improved. This allows for more accurate fitting and fewer painful pressure points, which directly influences daily wear time.

Comfort is not a luxury but a necessity for consistent use. A comfortable prosthetic encourages movement, participation, and confidence. Waiting for the right window allows comfort to become a foundation rather than an ongoing struggle.

Although waiting may feel like a delay, patients who begin prosthetic fitting at the right time often progress faster overall because their bodies are better prepared to learn and adapt. Training sessions become more productive, and setbacks are fewer.

This efficiency reduces total rehabilitation time and emotional strain. Patients feel that their effort leads to visible improvement, which reinforces motivation. Proper timing therefore saves time in the long run rather than wasting it.

Long-term prosthetic acceptance is closely linked to early experiences. When fitting begins during a period of physical and emotional stability, patients are more likely to integrate the prosthetic into daily life and continue using it over time.

For oncology survivors, acceptance also means viewing the prosthetic as part of recovery rather than a reminder of illness. This positive association supports identity rebuilding and emotional healing. Timing plays a central role in shaping this relationship.

Waiting for prosthetic readiness does not mean inactivity, because pre-prosthetic rehabilitation plays a crucial role in preparing the body for future fitting. Strengthening core muscles, maintaining joint range, and practicing balance exercises within safe limits all improve eventual outcomes.

This preparation phase also helps patients regain a sense of agency, which is especially important after the loss of control that often accompanies cancer treatment. Active participation in recovery builds confidence and reduces anxiety about future prosthetic use.

Education during the waiting period helps patients understand what to expect, reducing fear and unrealistic expectations. Learning about socket fit, training stages, and possible challenges prepares patients mentally for the journey ahead.

When patients know why waiting is necessary and how it benefits them, frustration decreases. Education transforms waiting from passive delay into active preparation, which improves engagement once fitting begins.

Emotional readiness is as important as physical readiness in oncology-related prosthetic care. Counseling or peer support during the waiting phase can help patients process grief, fear, and uncertainty in a healthy way.

Patients who feel emotionally supported are more resilient during rehabilitation. Addressing emotional needs early prevents them from becoming barriers later. This holistic approach strengthens overall outcomes.

In oncology-related amputation, ethical prosthetic care begins with respecting the patient’s individual pace of recovery rather than following rigid timelines. Cancer affects each person differently, and recovery is influenced by treatment type, overall health, emotional resilience, and social support. Applying a fixed schedule for prosthetic fitting ignores these realities and increases the risk of harm.

Patient-centered timing means listening carefully to how the patient feels physically and emotionally. Some may express eagerness to begin prosthetic use, while others may feel hesitant or fearful. Both responses provide valuable information. Respecting the patient’s pace does not mean delaying indefinitely, but it does mean aligning decisions with readiness rather than external pressure.

External pressure often comes from well-meaning family members who want visible signs of recovery or from societal expectations around rehabilitation speed. In oncology cases, this pressure can be intense because survival itself is already a major milestone. Prosthetic fitting may be seen as proof that life is returning to normal.

Clinicians have an ethical responsibility to manage these expectations with clear, compassionate communication. Explaining the medical reasons for waiting helps families understand that timing decisions are made to protect long-term health and function. When expectations are managed early, patients feel less rushed and more supported throughout the process.

Ethical timing decisions require shared understanding among patients, families, and care teams. Patients must be fully informed about the benefits and risks of both early and delayed fitting. This includes honest discussion about fatigue, training demands, and possible setbacks.

Shared decision-making empowers patients and reduces regret. When individuals feel that they participated actively in timing decisions, they are more likely to commit to rehabilitation and adapt positively to challenges. Ethical care prioritizes understanding over compliance.

Lower limb amputations following cancer treatment place significant demands on the body, particularly during prosthetic use. Walking with a prosthetic requires strength, balance, and cardiovascular endurance, all of which may be reduced after chemotherapy or radiation. Timing decisions must therefore be especially cautious.

For these patients, readiness often depends on stable wound healing, controlled swelling, and sufficient strength to support body weight safely. Even when these criteria are met, gradual introduction is essential to avoid overload. Lower limb prosthetic fitting is most successful when the body has regained enough reserve to handle the increased energy demand.

Upper limb prosthetic timing follows different considerations because energy demands are lower, but fine motor control and comfort are critical. Cancer-related nerve damage, scarring, and skin sensitivity can affect prosthetic tolerance and function.

Patients may be eager to regain hand function for daily tasks, but early fitting can be frustrating if pain or weakness limits control. Timing should allow for adequate healing and desensitization so that early experiences with the prosthetic are productive rather than discouraging. Patience supports better functional learning.

High-level amputations, such as hip disarticulation or shoulder-level loss, present unique challenges in oncology cases. These procedures are often associated with extensive surgery and prolonged recovery. Prosthetic fitting in such cases requires careful evaluation of overall health, motivation, and long-term goals.

For some patients, prosthetic use may not be the most appropriate option, especially if energy demands exceed sustainable capacity. Honest discussions about alternatives, such as mobility aids or adaptive strategies, are essential. Appropriate timing also includes recognizing when prosthetics may not add meaningful benefit.

The period immediately following prosthetic fitting is critical in oncology patients, because the body may still be adapting to post-treatment changes. Close monitoring during this phase helps identify skin issues, pain patterns, or fatigue before they become serious problems.

Frequent check-ins allow for timely adjustments to socket fit, alignment, and training intensity. This proactive approach reduces the risk of setbacks and reinforces patient confidence. Early surveillance is an investment in long-term success.

Cancer survivors may experience changes in health months or even years after treatment, including late radiation effects, recurrence, or unrelated illnesses. Prosthetic use and goals must adapt to these changes without framing them as failures.

Reducing wear time, simplifying components, or modifying training goals may be necessary during periods of reduced health. Flexibility ensures that prosthetics remain supportive rather than burdensome. Ongoing reassessment is a hallmark of patient-centered oncology prosthetic care.

Sustainable use means that the prosthetic fits comfortably into daily life without causing excessive fatigue or stress. For oncology survivors, sustainability often matters more than maximum function. Devices that support consistent, safe use contribute more to quality of life than those used only occasionally.

Long-term support from care teams reinforces sustainability. Regular follow-up, education, and encouragement help patients maintain healthy habits and address concerns early. Sustained engagement leads to better outcomes and greater satisfaction.

Manufacturers have a responsibility to design prosthetic solutions that account for the unique challenges faced by oncology patients, including sensitive skin, scarring, and fluctuating limb volume. Lightweight materials and adaptable socket designs can improve comfort and reduce stress on healing tissues.

Designs should allow for easy adjustments as the limb changes over time. Flexibility supports ongoing recovery and reduces the need for complete refitting. Patient comfort and safety must guide design decisions.

Manufacturers can support clinical decision-making by providing clear information about appropriate use, limitations, and maintenance of prosthetic components in oncology contexts. Educational resources help clinicians match devices to patient readiness and avoid overuse or misuse.

Patient-friendly guides are equally important. Simple explanations about care, wear schedules, and warning signs empower patients to participate actively in their recovery. Education strengthens outcomes and reduces anxiety.

Oncology-related prosthetic care is often a long journey with changing needs. Manufacturers who view their role as a long-term partnership rather than a one-time transaction can make a meaningful difference. Ongoing support, service access, and responsiveness build trust with both patients and care teams.

This commitment aligns with ethical, patient-centered care. By supporting individuals throughout recovery and beyond, manufacturers contribute to more humane and effective prosthetic outcomes.

Determining when prosthetic fitting is clinically appropriate after oncology-related amputation is not simply a technical decision. It is a form of care that reflects respect for healing, recovery, and the lived experience of cancer survivors. Timing shapes safety, confidence, and long-term acceptance.

At Robobionics, our experience has shown that waiting for the right clinical window leads to better outcomes across physical, emotional, and functional dimensions. Patients who begin prosthetic use when their bodies and minds are ready progress more smoothly and integrate their devices more fully into daily life.

Oncology-related amputation is a journey of survival, adaptation, and resilience. When prosthetic fitting is guided by clinical readiness rather than urgency, it becomes a supportive step in that journey rather than an added burden. Timing, when handled with care and insight, can be one of the most powerful tools in prosthetic rehabilitation.

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

For trauma amputees, the journey does not begin at the prosthetic clinic. It begins much

Amputation after cancer is not just a surgical event. It is the end of one

When a child loses a limb, the challenge is never only physical. A child’s body

Last updated: November 10, 2022

Thank you for shopping at Robo Bionics.

If, for any reason, You are not completely satisfied with a purchase We invite You to review our policy on refunds and returns.

The following terms are applicable for any products that You purchased with Us.

The words of which the initial letter is capitalized have meanings defined under the following conditions. The following definitions shall have the same meaning regardless of whether they appear in singular or in plural.

For the purposes of this Return and Refund Policy:

Company (referred to as either “the Company”, “Robo Bionics”, “We”, “Us” or “Our” in this Agreement) refers to Bionic Hope Private Limited, Pearl Haven, 1st Floor Kumbharwada, Manickpur Near St. Michael’s Church Vasai Road West, Palghar Maharashtra 401202.

Goods refer to the items offered for sale on the Website.

Orders mean a request by You to purchase Goods from Us.

Service refers to the Services Provided like Online Demo and Live Demo.

Website refers to Robo Bionics, accessible from https://robobionics.in

You means the individual accessing or using the Service, or the company, or other legal entity on behalf of which such individual is accessing or using the Service, as applicable.

You are entitled to cancel Your Service Bookings within 7 days without giving any reason for doing so, before completion of Delivery.

The deadline for cancelling a Service Booking is 7 days from the date on which You received the Confirmation of Service.

In order to exercise Your right of cancellation, You must inform Us of your decision by means of a clear statement. You can inform us of your decision by:

We will reimburse You no later than 7 days from the day on which We receive your request for cancellation, if above criteria is met. We will use the same means of payment as You used for the Service Booking, and You will not incur any fees for such reimbursement.

Please note in case you miss a Service Booking or Re-schedule the same we shall only entertain the request once.

In order for the Goods to be eligible for a return, please make sure that:

The following Goods cannot be returned:

We reserve the right to refuse returns of any merchandise that does not meet the above return conditions in our sole discretion.

Only regular priced Goods may be refunded by 50%. Unfortunately, Goods on sale cannot be refunded. This exclusion may not apply to You if it is not permitted by applicable law.

You are responsible for the cost and risk of returning the Goods to Us. You should send the Goods at the following:

We cannot be held responsible for Goods damaged or lost in return shipment. Therefore, We recommend an insured and trackable courier service. We are unable to issue a refund without actual receipt of the Goods or proof of received return delivery.

If you have any questions about our Returns and Refunds Policy, please contact us:

Last Updated on: 1st Jan 2021

These Terms and Conditions (“Terms”) govern Your access to and use of the website, platforms, applications, products and services (ively, the “Services”) offered by Robo Bionics® (a registered trademark of Bionic Hope Private Limited, also used as a trade name), a company incorporated under the Companies Act, 2013, having its Corporate office at Pearl Heaven Bungalow, 1st Floor, Manickpur, Kumbharwada, Vasai Road (West), Palghar – 401202, Maharashtra, India (“Company”, “We”, “Us” or “Our”). By accessing or using the Services, You (each a “User”) agree to be bound by these Terms and all applicable laws and regulations. If You do not agree with any part of these Terms, You must immediately discontinue use of the Services.

1.1 “Individual Consumer” means a natural person aged eighteen (18) years or above who registers to use Our products or Services following evaluation and prescription by a Rehabilitation Council of India (“RCI”)–registered Prosthetist.

1.2 “Entity Consumer” means a corporate organisation, nonprofit entity, CSR sponsor or other registered organisation that sponsors one or more Individual Consumers to use Our products or Services.

1.3 “Clinic” means an RCI-registered Prosthetics and Orthotics centre or Prosthetist that purchases products and Services from Us for fitment to Individual Consumers.

1.4 “Platform” means RehabConnect™, Our online marketplace by which Individual or Entity Consumers connect with Clinics in their chosen locations.

1.5 “Products” means Grippy® Bionic Hand, Grippy® Mech, BrawnBand™, WeightBand™, consumables, accessories and related hardware.

1.6 “Apps” means Our clinician-facing and end-user software applications supporting Product use and data collection.

1.7 “Impact Dashboard™” means the analytics interface provided to CSR, NGO, corporate and hospital sponsors.

1.8 “Services” includes all Products, Apps, the Platform and the Impact Dashboard.

2.1 Individual Consumers must be at least eighteen (18) years old and undergo evaluation and prescription by an RCI-registered Prosthetist prior to purchase or use of any Products or Services.

2.2 Entity Consumers must be duly registered under the laws of India and may sponsor one or more Individual Consumers.

2.3 Clinics must maintain valid RCI registration and comply with all applicable clinical and professional standards.

3.1 Robo Bionics acts solely as an intermediary connecting Users with Clinics via the Platform. We do not endorse or guarantee the quality, legality or outcomes of services rendered by any Clinic. Each Clinic is solely responsible for its professional services and compliance with applicable laws and regulations.

4.1 All content, trademarks, logos, designs and software on Our website, Apps and Platform are the exclusive property of Bionic Hope Private Limited or its licensors.

4.2 Subject to these Terms, We grant You a limited, non-exclusive, non-transferable, revocable license to use the Services for personal, non-commercial purposes.

4.3 You may not reproduce, modify, distribute, decompile, reverse engineer or create derivative works of any portion of the Services without Our prior written consent.

5.1 Limited Warranty. We warrant that Products will be free from workmanship defects under normal use as follows:

(a) Grippy™ Bionic Hand, BrawnBand® and WeightBand®: one (1) year from date of purchase, covering manufacturing defects only.

(b) Chargers and batteries: six (6) months from date of purchase.

(c) Grippy Mech™: three (3) months from date of purchase.

(d) Consumables (e.g., gloves, carry bags): no warranty.

5.2 Custom Sockets. Sockets fabricated by Clinics are covered only by the Clinic’s optional warranty and subject to physiological changes (e.g., stump volume, muscle sensitivity).

5.3 Exclusions. Warranty does not apply to damage caused by misuse, user negligence, unauthorised repairs, Acts of God, or failure to follow the Instruction Manual.

5.4 Claims. To claim warranty, You must register the Product online, provide proof of purchase, and follow the procedures set out in the Warranty Card.

5.5 Disclaimer. To the maximum extent permitted by law, all other warranties, express or implied, including merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, are disclaimed.

6.1 We collect personal contact details, physiological evaluation data, body measurements, sensor calibration values, device usage statistics and warranty information (“User Data”).

6.2 User Data is stored on secure servers of our third-party service providers and transmitted via encrypted APIs.

6.3 By using the Services, You consent to collection, storage, processing and transfer of User Data within Our internal ecosystem and to third-party service providers for analytics, R&D and support.

6.4 We implement reasonable security measures and comply with the Information Technology Act, 2000, and Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

6.5 A separate Privacy Policy sets out detailed information on data processing, user rights, grievance redressal and cross-border transfers, which forms part of these Terms.

7.1 Pursuant to the Information Technology Rules, 2021, We have given the Charge of Grievance Officer to our QC Head:

- Address: Grievance Officer

- Email: support@robobionics.in

- Phone: +91-8668372127

7.2 All support tickets and grievances must be submitted exclusively via the Robo Bionics Customer Support portal at https://robobionics.freshdesk.com/.

7.3 We will acknowledge receipt of your ticket within twenty-four (24) working hours and endeavour to resolve or provide a substantive response within seventy-two (72) working hours, excluding weekends and public holidays.

8.1 Pricing. Product and Service pricing is as per quotations or purchase orders agreed in writing.

8.2 Payment. We offer (a) 100% advance payment with possible incentives or (b) stage-wise payment plans without incentives.

8.3 Refunds. No refunds, except pro-rata adjustment where an Individual Consumer is medically unfit to proceed or elects to withdraw mid-stage, in which case unused stage fees apply.

9.1 Users must follow instructions provided by RCI-registered professionals and the User Manual.

9.2 Users and Entity Consumers shall indemnify and hold Us harmless from all liabilities, claims, damages and expenses arising from misuse of the Products, failure to follow professional guidance, or violation of these Terms.

10.1 To the extent permitted by law, Our total liability for any claim arising out of or in connection with these Terms or the Services shall not exceed the aggregate amount paid by You to Us in the twelve (12) months preceding the claim.

10.2 We shall not be liable for any indirect, incidental, consequential or punitive damages, including loss of profit, data or goodwill.

11.1 Our Products are classified as “Rehabilitation Aids,” not medical devices for diagnostic purposes.

11.2 Manufactured under ISO 13485:2016 quality management and tested for electrical safety under IEC 60601-1 and IEC 60601-1-2.

11.3 Products shall only be used under prescription and supervision of RCI-registered Prosthetists, Physiotherapists or Occupational Therapists.

We do not host third-party content or hardware. Any third-party services integrated with Our Apps are subject to their own terms and privacy policies.

13.1 All intellectual property rights in the Services and User Data remain with Us or our licensors.

13.2 Users grant Us a perpetual, irrevocable, royalty-free licence to use anonymised usage data for analytics, product improvement and marketing.

14.1 We may amend these Terms at any time. Material changes shall be notified to registered Users at least thirty (30) days prior to the effective date, via email and website notice.

14.2 Continued use of the Services after the effective date constitutes acceptance of the revised Terms.

Neither party shall be liable for delay or failure to perform any obligation under these Terms due to causes beyond its reasonable control, including Acts of God, pandemics, strikes, war, terrorism or government regulations.

16.1 All disputes shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

16.2 A sole arbitrator shall be appointed by Bionic Hope Private Limited or, failing agreement within thirty (30) days, by the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration.

16.3 Seat of arbitration: Mumbai, India.

16.4 Governing law: Laws of India.

16.5 Courts at Mumbai have exclusive jurisdiction over any proceedings to enforce an arbitral award.

17.1 Severability. If any provision is held invalid or unenforceable, the remainder shall remain in full force.

17.2 Waiver. No waiver of any breach shall constitute a waiver of any subsequent breach of the same or any other provision.

17.3 Assignment. You may not assign your rights or obligations without Our prior written consent.

By accessing or using the Products and/or Services of Bionic Hope Private Limited, You acknowledge that You have read, understood and agree to be bound by these Terms and Conditions.