Post-Op Follow-Up Schedule That Prevents Prosthetic Delays (For Clinicians)

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

Returning to work after a serious injury or limb loss is not just about healing the body. It is about trust, safety, confidence, and function coming together at the right time. Doctors are often asked one simple question: “Is this person ready to work again?” The answer is rarely simple. This article explains how return-to-work decisions should be made, what functional signs truly matter, and how doctors can assess readiness in a way that protects dignity, productivity, and long-term health.

Returning to work is often treated like a yes or no decision. In reality, it is a layered process that needs careful thought.

A person may look healed on the outside but still struggle with strength, balance, or endurance.

Doctors must look beyond reports and scans to understand real work readiness.

When people return too early, injuries can worsen. Pain may increase and confidence can drop.

This often leads to repeated sick leave or job loss.

A slow, well-judged return protects both health and career.

Waiting too long also has risks. Skills may fade and confidence may reduce.

People may begin to doubt their ability to work at all.

The goal is not speed or delay, but correct timing.

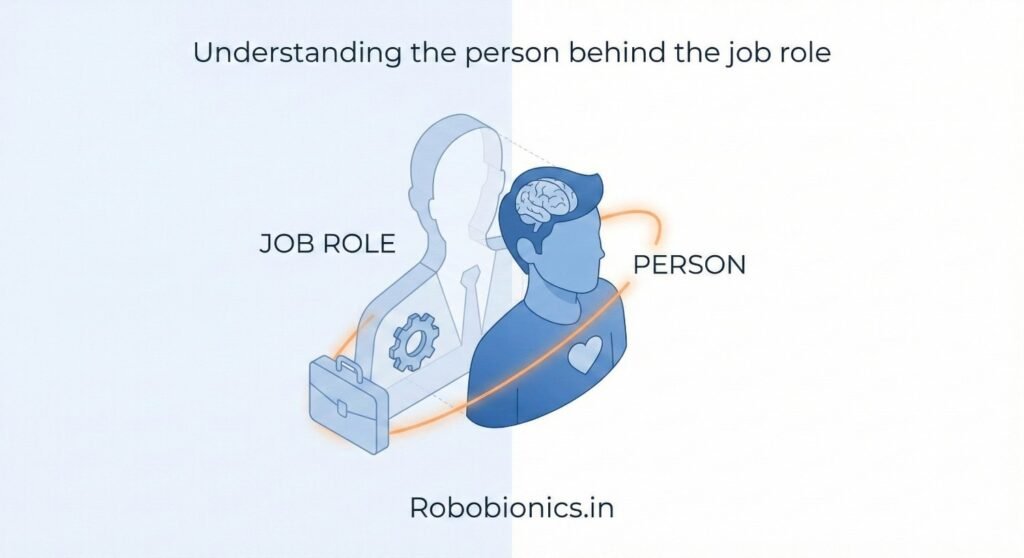

Two people with the same job title may do very different work.

One may sit at a desk, while another may move, lift, or travel often.

Doctors must understand the actual tasks, not just the role name.

Some jobs require standing for long hours. Others need fine hand control or strength.

Understanding how often tasks are repeated is important.

Small movements done all day can cause more strain than heavy work done rarely.

Work also demands focus, decision-making, and stress handling.

Pain, fatigue, or fear of re-injury can affect these abilities.

A return-to-work plan must consider mental readiness too.

A bone may heal, or a wound may close, but function may still be limited.

Stiffness, weakness, or loss of control can remain.

Doctors must assess what the person can actually do, not just what has healed.

Clinic tests are done in controlled spaces. Work happens in real, often messy environments.

Uneven floors, noise, heat, and pressure all affect performance.

Functional testing should reflect real work conditions as much as possible.

How a person moves matters more than how much they can lift once.

Poor movement patterns can lead to new injuries.

Doctors should watch posture, balance, and effort closely.

Strength tests often focus on short bursts of effort.

Work usually requires steady effort over hours.

Endurance is often the missing piece in return-to-work decisions.

Fatigue can change how the body moves and reacts.

A person may start strong but lose control as they tire.

Doctors should assess performance over time, not just at the start.

Not every job needs high strength.

Doctors should match measured strength to actual job demands.

This avoids both overestimation and unnecessary restriction.

Limited joint movement can force the body into unsafe positions.

This increases the risk of strain or falls.

Work readiness depends on safe movement, not perfect movement.

Full range of motion is ideal, but functional range may be enough.

Doctors should ask if the available movement supports job tasks.

This practical approach helps realistic decision-making.

Many injuries occur when joints move beyond control.

Doctors should assess how well a person controls movement limits.

This is especially important for lifting and reaching tasks.

Pain does not always mean damage, but it affects performance.

Ignoring pain reports can harm trust between doctor and patient.

Pain should be understood, not dismissed.

Some pain may be manageable during work.

Other pain may reduce focus or strength.

Doctors should help patients identify safe pain levels.

Pain that increases steadily with activity is a warning sign.

Pain that settles with rest may be manageable.

These patterns guide safe return planning.

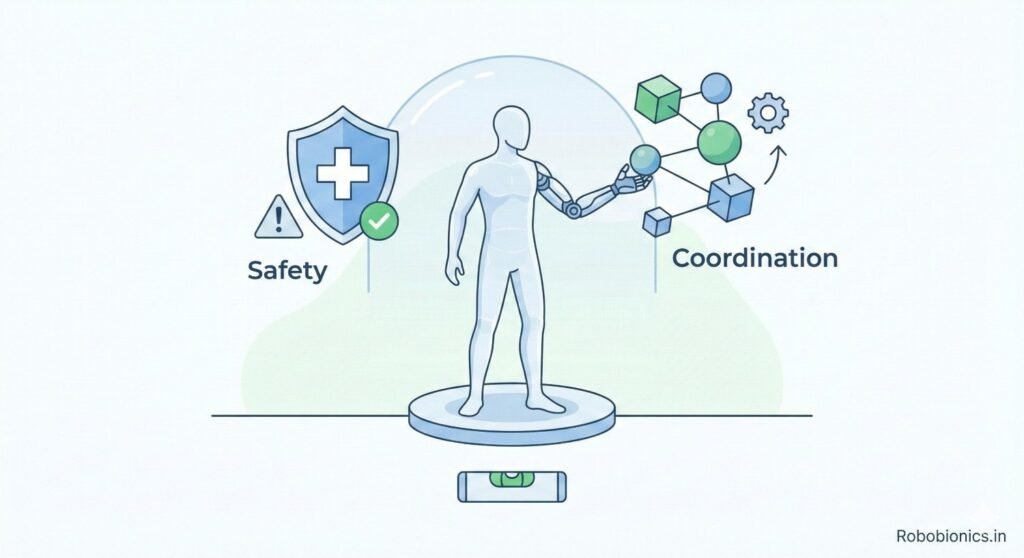

Balance affects how we sit, stand, and move.

Poor balance increases fall risk, even indoors.

Doctors should not ignore balance in return-to-work checks.

Some jobs need precise hand or foot control.

Coordination issues can reduce work quality and safety.

Simple coordination tests can reveal hidden challenges.

Slow reactions increase accident risk.

Fatigue, pain, or medication can affect alertness.

Doctors should consider these factors carefully.

Pain and stress can reduce focus.

Some medications may cause drowsiness.

Cognitive readiness is as important as physical readiness.

Work often involves quick choices.

Doctors should assess how stress affects the person.

Simple discussions can reveal readiness levels.

Complex jobs need memory and planning.

Injuries and trauma can affect these skills.

These areas should not be overlooked.

Braces, supports, or prosthetics can improve function.

They may reduce strain and improve safety.

Doctors should assess work readiness with these devices in place.

Using a device well takes practice.

Return-to-work should not start before comfort is achieved.

Training reduces errors and builds confidence.

Not all devices suit all jobs.

Doctors should confirm that devices match work demands.

Regular review improves long-term outcomes.

A supportive workplace can bridge functional gaps.

Poor environments increase risk and stress.

Doctors should ask about workplace conditions.

Simple changes can make a big difference.

Task rotation, seating changes, or tool modification help.

Doctors can guide these decisions.

Clear communication reduces misunderstanding.

Doctors play a key role in setting realistic expectations.

This protects both worker and employer.

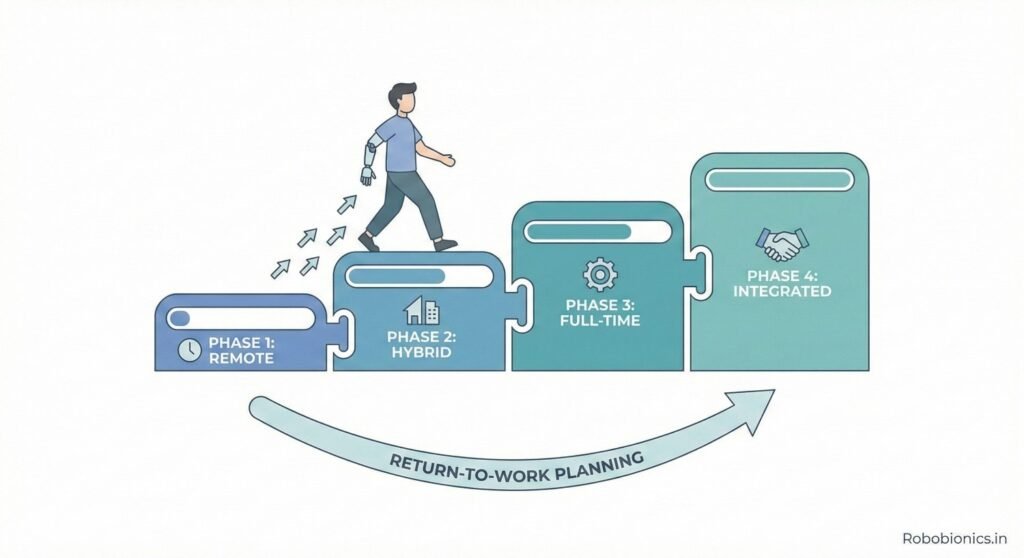

Starting full-time work suddenly can overwhelm the body.

Phased return allows adaptation.

This reduces injury and burnout risk.

Return-to-work is not a one-time decision.

Regular check-ins help adjust plans.

Flexibility improves success rates.

Setbacks can happen.

Doctors should encourage reporting issues early.

Timely adjustments prevent long-term problems.

Success is not just attendance.

Quality, safety, and comfort matter.

Doctors should assess these outcomes.

Confidence affects performance.

Fear can limit ability even when physically ready.

Doctors should ask about emotional state.

The goal is not short-term return.

Work should be sustainable without harming health.

This defines true success.

Muscle and joint injuries often heal on scans before function fully returns. Stiffness, weakness, and fear of movement can stay longer.

Doctors should assess how smoothly the person moves during work-like actions. Jerky or guarded movement often signals incomplete readiness.

Work tasks that involve repetition need special attention, as small limits can grow into big problems over time.

Nerve injuries heal slowly and sometimes unevenly. Strength may return without control, or sensation may remain altered.

Doctors should assess fine control, grip quality, and reaction to unexpected movement. These are critical for safe work.

Return-to-work decisions must remain flexible, as nerve recovery can change over months.

For people using prosthetics, work readiness depends on skill, comfort, and trust in the device.

Doctors should assess work tasks with the prosthetic in place, not without it.

True readiness comes when the person uses the device naturally, without constant mental effort.

Strong grip does not always mean useful grip. Control matters more than force in most jobs.

Doctors should observe how objects are held, released, and adjusted.

Dropping or crushing objects signals poor functional control.

Hands are often used continuously at work. Short tests may miss fatigue-related issues.

Doctors should assess performance over longer task periods.

Endurance failure often appears only after repeated use.

Reduced sensation increases injury risk. Heat, sharp edges, or vibration may go unnoticed.

Doctors should assess protective sensation and awareness.

Work may need adjustments if sensation is reduced.

Many jobs involve walking more than people realize.

Doctors should assess walking over time and on uneven surfaces.

Fatigue-related limping increases injury risk.

Standing for long hours stresses joints and spine.

Doctors should assess posture changes over time.

Pain or shifting weight often signals limited tolerance.

For lower limb prosthetic users, fit and comfort matter greatly.

Doctors should assess gait with real footwear and work conditions.

Confidence in movement predicts long-term success.

Fatigue is common after injury, even when strength returns.

It affects focus, reaction, and mood.

Doctors should ask about daily energy patterns.

Some jobs drain energy faster than others.

Doctors should match energy levels to job rhythm.

This prevents burnout and setbacks.

Work plans should include rest breaks when needed.

Ignoring recovery needs reduces long-term work ability.

Doctors should guide realistic pacing.

Fear can limit movement more than physical limits.

Doctors should listen carefully to these concerns.

Gradual exposure builds confidence safely.

Injury can affect how people see themselves at work.

Doctors should assess confidence in handling job demands.

Supportive planning rebuilds professional identity.

Work stress can worsen pain and fatigue.

Doctors should assess stress handling ability.

Mental readiness protects physical recovery.

Pain or fatigue can reduce patience and clarity.

Some injuries affect speech or expression.

Doctors should consider these factors for client-facing roles.

Supportive teams ease return-to-work.

Doctors can encourage open discussion with employers.

Good communication prevents misunderstandings.

Clear role expectations reduce pressure.

Doctors help by setting realistic limits.

This protects trust on all sides.

Doctors must protect patients from harm.

Approving return too early can cause damage.

Safety must come before pressure.

An unready worker may endanger others.

Doctors must consider wider impact.

This makes assessment even more important.

Written guidance helps employers act responsibly.

Vague notes create confusion.

Clarity protects everyone involved.

No single test defines readiness.

Doctors should combine observation, reports, and discussion.

A holistic view leads to better decisions.

Readiness changes with recovery and work exposure.

Regular reassessment improves outcomes.

Return-to-work is a process, not an event.

Patients often sense limits before tests show them.

Doctors should value this insight.

Trust improves honesty and outcomes.

Pain increase, fatigue, or reduced performance signal issues.

Doctors should encourage early reporting.

Timely action prevents setbacks.

Jobs may need further modification.

Doctors should remain involved beyond clearance.

Flexibility supports sustainability.

Some injuries change long-term capacity.

Doctors can help plan realistic career paths.

This protects dignity and income.

Doctors should work with therapists and prosthetists.

Shared insight improves assessment accuracy.

Teamwork benefits the patient most.

Rehabilitation should mirror real work.

This prepares the body and mind together.

Doctors can guide this focus.

The shift should be smooth, not sudden.

Clear handover reduces confusion.

This supports confidence.

Activity data can show real endurance levels.

Doctors can use this to guide decisions.

Objective data supports judgement.

Simulated tasks reveal hidden limits.

They bridge the gap between clinic and workplace.

Doctors should use them when possible.

Remote check-ins improve monitoring.

This is useful for long-term guidance.

Care continues beyond the clinic.

Success includes comfort, safety, and confidence.

Working without fear matters.

Doctors should define success broadly.

Short-term return is not enough.

Work should be maintainable for years.

This is the real goal.

Work is part of life, not all of it.

Doctors should align decisions with personal goals.

This keeps care human.

Medical reports often show healing, but they do not show how a person moves or copes during a full workday.

Doctors who rely only on reports may miss hidden risks.

Observation and discussion are just as important as test results.

Some patients underreport problems due to fear of losing their job.

Others may overstate ability out of pressure to return.

Doctors should create a safe space for honest conversation.

Many see clearance as the end of care.

In reality, it is the start of a new phase.

Ongoing support reduces failure rates.

Therapy sessions are planned and controlled.

Workdays are long and unpredictable.

Gradual exposure helps the body adjust safely.

One good day does not mean full readiness.

Doctors should look for consistent performance.

Patterns matter more than single results.

Needing more time is not failure.

Doctors should reinforce this message.

Confidence grows when pressure reduces.

Supportive workplaces improve outcomes.

Simple understanding reduces stress.

Doctors can encourage this culture.

Ignoring restrictions can cause re-injury.

Employers should follow recommended limits.

Clear communication helps compliance.

Return-to-work is a shared process.

Doctors, employers, and workers all play roles.

Shared goals improve success.

Many workers return early due to financial stress.

Doctors should understand this reality.

Sensitive planning is needed.

Many jobs lack formal safety measures.

Doctors should ask detailed questions.

Advice must match real conditions.

Doctors can help reframe recovery as strength.

This supports mental health.

Not all devices suit all tasks.

Doctors should assess function in real conditions.

This avoids misuse and frustration.

Using devices well takes time.

Return-to-work should follow skill mastery.

This improves safety.

Work demands may change.

Devices should adapt accordingly.

Regular review is essential.

Some injuries change capacity permanently.

Doctors should communicate this gently.

Honesty helps planning.

Role changes or new careers may be needed.

Doctors can guide realistic choices.

This protects dignity.

Career change can be painful.

Doctors should acknowledge this loss.

Support eases adjustment.

Reports should guide action, not confuse.

Specific limits help employers plan.

Clarity reduces conflict.

Words like “light duty” mean different things.

Doctors should define terms clearly.

Precision improves safety.

Conditions change with time.

Reports should reflect current ability.

Regular updates support trust.

Many doctors are not trained in work-focused evaluation.

Training improves confidence and accuracy.

This benefits patients.

Therapists offer practical insight.

Collaboration improves judgement.

Shared learning strengthens care.

Understanding lived experience matters.

Empathy improves communication.

Better relationships lead to better outcomes.

Overcompensation can cause new problems.

Doctors should watch for this.

Early advice prevents damage.

Posture, breaks, and pacing matter.

Doctors can guide simple habits.

Small changes protect health.

Work ability changes with age.

Doctors should help plan ahead.

This ensures long-term stability.

Time since injury is less important than function.

Doctors should assess ability, not dates.

This leads to safer decisions.

Work supports dignity and independence.

Health protects long-term earning ability.

Both must be balanced carefully.

At the heart of return-to-work is a person, not a file.

Listening, observing, and guiding with care makes the difference.

This is how return-to-work decisions truly serve everyone.

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

For trauma amputees, the journey does not begin at the prosthetic clinic. It begins much

Amputation after cancer is not just a surgical event. It is the end of one

When a child loses a limb, the challenge is never only physical. A child’s body

Last updated: November 10, 2022

Thank you for shopping at Robo Bionics.

If, for any reason, You are not completely satisfied with a purchase We invite You to review our policy on refunds and returns.

The following terms are applicable for any products that You purchased with Us.

The words of which the initial letter is capitalized have meanings defined under the following conditions. The following definitions shall have the same meaning regardless of whether they appear in singular or in plural.

For the purposes of this Return and Refund Policy:

Company (referred to as either “the Company”, “Robo Bionics”, “We”, “Us” or “Our” in this Agreement) refers to Bionic Hope Private Limited, Pearl Haven, 1st Floor Kumbharwada, Manickpur Near St. Michael’s Church Vasai Road West, Palghar Maharashtra 401202.

Goods refer to the items offered for sale on the Website.

Orders mean a request by You to purchase Goods from Us.

Service refers to the Services Provided like Online Demo and Live Demo.

Website refers to Robo Bionics, accessible from https://robobionics.in

You means the individual accessing or using the Service, or the company, or other legal entity on behalf of which such individual is accessing or using the Service, as applicable.

You are entitled to cancel Your Service Bookings within 7 days without giving any reason for doing so, before completion of Delivery.

The deadline for cancelling a Service Booking is 7 days from the date on which You received the Confirmation of Service.

In order to exercise Your right of cancellation, You must inform Us of your decision by means of a clear statement. You can inform us of your decision by:

We will reimburse You no later than 7 days from the day on which We receive your request for cancellation, if above criteria is met. We will use the same means of payment as You used for the Service Booking, and You will not incur any fees for such reimbursement.

Please note in case you miss a Service Booking or Re-schedule the same we shall only entertain the request once.

In order for the Goods to be eligible for a return, please make sure that:

The following Goods cannot be returned:

We reserve the right to refuse returns of any merchandise that does not meet the above return conditions in our sole discretion.

Only regular priced Goods may be refunded by 50%. Unfortunately, Goods on sale cannot be refunded. This exclusion may not apply to You if it is not permitted by applicable law.

You are responsible for the cost and risk of returning the Goods to Us. You should send the Goods at the following:

We cannot be held responsible for Goods damaged or lost in return shipment. Therefore, We recommend an insured and trackable courier service. We are unable to issue a refund without actual receipt of the Goods or proof of received return delivery.

If you have any questions about our Returns and Refunds Policy, please contact us:

Last Updated on: 1st Jan 2021

These Terms and Conditions (“Terms”) govern Your access to and use of the website, platforms, applications, products and services (ively, the “Services”) offered by Robo Bionics® (a registered trademark of Bionic Hope Private Limited, also used as a trade name), a company incorporated under the Companies Act, 2013, having its Corporate office at Pearl Heaven Bungalow, 1st Floor, Manickpur, Kumbharwada, Vasai Road (West), Palghar – 401202, Maharashtra, India (“Company”, “We”, “Us” or “Our”). By accessing or using the Services, You (each a “User”) agree to be bound by these Terms and all applicable laws and regulations. If You do not agree with any part of these Terms, You must immediately discontinue use of the Services.

1.1 “Individual Consumer” means a natural person aged eighteen (18) years or above who registers to use Our products or Services following evaluation and prescription by a Rehabilitation Council of India (“RCI”)–registered Prosthetist.

1.2 “Entity Consumer” means a corporate organisation, nonprofit entity, CSR sponsor or other registered organisation that sponsors one or more Individual Consumers to use Our products or Services.

1.3 “Clinic” means an RCI-registered Prosthetics and Orthotics centre or Prosthetist that purchases products and Services from Us for fitment to Individual Consumers.

1.4 “Platform” means RehabConnect™, Our online marketplace by which Individual or Entity Consumers connect with Clinics in their chosen locations.

1.5 “Products” means Grippy® Bionic Hand, Grippy® Mech, BrawnBand™, WeightBand™, consumables, accessories and related hardware.

1.6 “Apps” means Our clinician-facing and end-user software applications supporting Product use and data collection.

1.7 “Impact Dashboard™” means the analytics interface provided to CSR, NGO, corporate and hospital sponsors.

1.8 “Services” includes all Products, Apps, the Platform and the Impact Dashboard.

2.1 Individual Consumers must be at least eighteen (18) years old and undergo evaluation and prescription by an RCI-registered Prosthetist prior to purchase or use of any Products or Services.

2.2 Entity Consumers must be duly registered under the laws of India and may sponsor one or more Individual Consumers.

2.3 Clinics must maintain valid RCI registration and comply with all applicable clinical and professional standards.

3.1 Robo Bionics acts solely as an intermediary connecting Users with Clinics via the Platform. We do not endorse or guarantee the quality, legality or outcomes of services rendered by any Clinic. Each Clinic is solely responsible for its professional services and compliance with applicable laws and regulations.

4.1 All content, trademarks, logos, designs and software on Our website, Apps and Platform are the exclusive property of Bionic Hope Private Limited or its licensors.

4.2 Subject to these Terms, We grant You a limited, non-exclusive, non-transferable, revocable license to use the Services for personal, non-commercial purposes.

4.3 You may not reproduce, modify, distribute, decompile, reverse engineer or create derivative works of any portion of the Services without Our prior written consent.

5.1 Limited Warranty. We warrant that Products will be free from workmanship defects under normal use as follows:

(a) Grippy™ Bionic Hand, BrawnBand® and WeightBand®: one (1) year from date of purchase, covering manufacturing defects only.

(b) Chargers and batteries: six (6) months from date of purchase.

(c) Grippy Mech™: three (3) months from date of purchase.

(d) Consumables (e.g., gloves, carry bags): no warranty.

5.2 Custom Sockets. Sockets fabricated by Clinics are covered only by the Clinic’s optional warranty and subject to physiological changes (e.g., stump volume, muscle sensitivity).

5.3 Exclusions. Warranty does not apply to damage caused by misuse, user negligence, unauthorised repairs, Acts of God, or failure to follow the Instruction Manual.

5.4 Claims. To claim warranty, You must register the Product online, provide proof of purchase, and follow the procedures set out in the Warranty Card.

5.5 Disclaimer. To the maximum extent permitted by law, all other warranties, express or implied, including merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, are disclaimed.

6.1 We collect personal contact details, physiological evaluation data, body measurements, sensor calibration values, device usage statistics and warranty information (“User Data”).

6.2 User Data is stored on secure servers of our third-party service providers and transmitted via encrypted APIs.

6.3 By using the Services, You consent to collection, storage, processing and transfer of User Data within Our internal ecosystem and to third-party service providers for analytics, R&D and support.

6.4 We implement reasonable security measures and comply with the Information Technology Act, 2000, and Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

6.5 A separate Privacy Policy sets out detailed information on data processing, user rights, grievance redressal and cross-border transfers, which forms part of these Terms.

7.1 Pursuant to the Information Technology Rules, 2021, We have given the Charge of Grievance Officer to our QC Head:

- Address: Grievance Officer

- Email: support@robobionics.in

- Phone: +91-8668372127

7.2 All support tickets and grievances must be submitted exclusively via the Robo Bionics Customer Support portal at https://robobionics.freshdesk.com/.

7.3 We will acknowledge receipt of your ticket within twenty-four (24) working hours and endeavour to resolve or provide a substantive response within seventy-two (72) working hours, excluding weekends and public holidays.

8.1 Pricing. Product and Service pricing is as per quotations or purchase orders agreed in writing.

8.2 Payment. We offer (a) 100% advance payment with possible incentives or (b) stage-wise payment plans without incentives.

8.3 Refunds. No refunds, except pro-rata adjustment where an Individual Consumer is medically unfit to proceed or elects to withdraw mid-stage, in which case unused stage fees apply.

9.1 Users must follow instructions provided by RCI-registered professionals and the User Manual.

9.2 Users and Entity Consumers shall indemnify and hold Us harmless from all liabilities, claims, damages and expenses arising from misuse of the Products, failure to follow professional guidance, or violation of these Terms.

10.1 To the extent permitted by law, Our total liability for any claim arising out of or in connection with these Terms or the Services shall not exceed the aggregate amount paid by You to Us in the twelve (12) months preceding the claim.

10.2 We shall not be liable for any indirect, incidental, consequential or punitive damages, including loss of profit, data or goodwill.

11.1 Our Products are classified as “Rehabilitation Aids,” not medical devices for diagnostic purposes.

11.2 Manufactured under ISO 13485:2016 quality management and tested for electrical safety under IEC 60601-1 and IEC 60601-1-2.

11.3 Products shall only be used under prescription and supervision of RCI-registered Prosthetists, Physiotherapists or Occupational Therapists.

We do not host third-party content or hardware. Any third-party services integrated with Our Apps are subject to their own terms and privacy policies.

13.1 All intellectual property rights in the Services and User Data remain with Us or our licensors.

13.2 Users grant Us a perpetual, irrevocable, royalty-free licence to use anonymised usage data for analytics, product improvement and marketing.

14.1 We may amend these Terms at any time. Material changes shall be notified to registered Users at least thirty (30) days prior to the effective date, via email and website notice.

14.2 Continued use of the Services after the effective date constitutes acceptance of the revised Terms.

Neither party shall be liable for delay or failure to perform any obligation under these Terms due to causes beyond its reasonable control, including Acts of God, pandemics, strikes, war, terrorism or government regulations.

16.1 All disputes shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

16.2 A sole arbitrator shall be appointed by Bionic Hope Private Limited or, failing agreement within thirty (30) days, by the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration.

16.3 Seat of arbitration: Mumbai, India.

16.4 Governing law: Laws of India.

16.5 Courts at Mumbai have exclusive jurisdiction over any proceedings to enforce an arbitral award.

17.1 Severability. If any provision is held invalid or unenforceable, the remainder shall remain in full force.

17.2 Waiver. No waiver of any breach shall constitute a waiver of any subsequent breach of the same or any other provision.

17.3 Assignment. You may not assign your rights or obligations without Our prior written consent.

By accessing or using the Products and/or Services of Bionic Hope Private Limited, You acknowledge that You have read, understood and agree to be bound by these Terms and Conditions.