Post-Op Follow-Up Schedule That Prevents Prosthetic Delays (For Clinicians)

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

Trauma-related amputation changes a life in a moment, but prosthetic care is a long clinical journey that must be planned with care, timing, and clear judgment. For doctors, the question is not only whether a limb can be fitted, but when it should be fitted and how to decide if the patient can truly benefit from it in the long term. Trauma patients often look strong on the outside, yet carry hidden physical and emotional risks that can affect outcomes.

This article explains the clinical criteria for prosthetic candidacy after trauma amputation, using a clear and practical approach suited to real hospitals and rehabilitation settings in India. It focuses on medical safety, functional readiness, emotional recovery, and real-life demands, so that prosthetic decisions support healing rather than rush it.

The aim is to help clinicians make confident, ethical, and patient-centered decisions that lead to safe use, consistent wear, and meaningful recovery.

Trauma amputations are different from planned or disease-related amputations because they happen suddenly and often involve multiple injuries at the same time.

The patient may be young, physically fit, and motivated, yet their body and mind may still be in shock.

This mix of strength and vulnerability is why trauma cases need a careful and structured approach.

A trauma patient may appear stable once wounds close and fractures heal, but deeper issues like nerve injury, muscle loss, or emotional distress can remain.

These factors may not show up in early exams but can strongly affect prosthetic success later.

Good candidacy decisions look beyond what is visible on the surface.

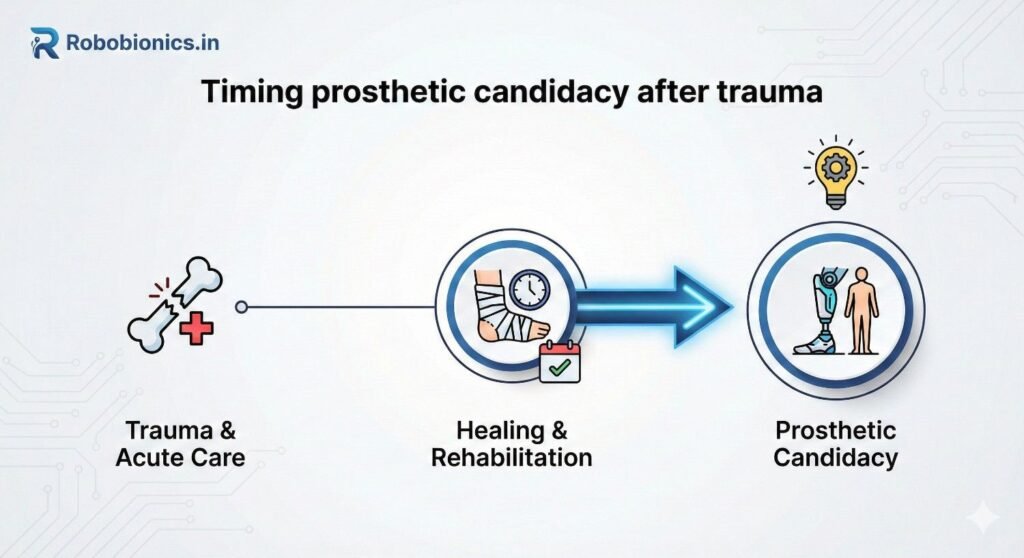

The first few clinical choices after trauma often set the direction for years.

Rushing into prosthetic fitting too early can cause setbacks, while waiting too long can reduce confidence and muscle strength.

Balanced timing is the core challenge in trauma-related prosthetic care.

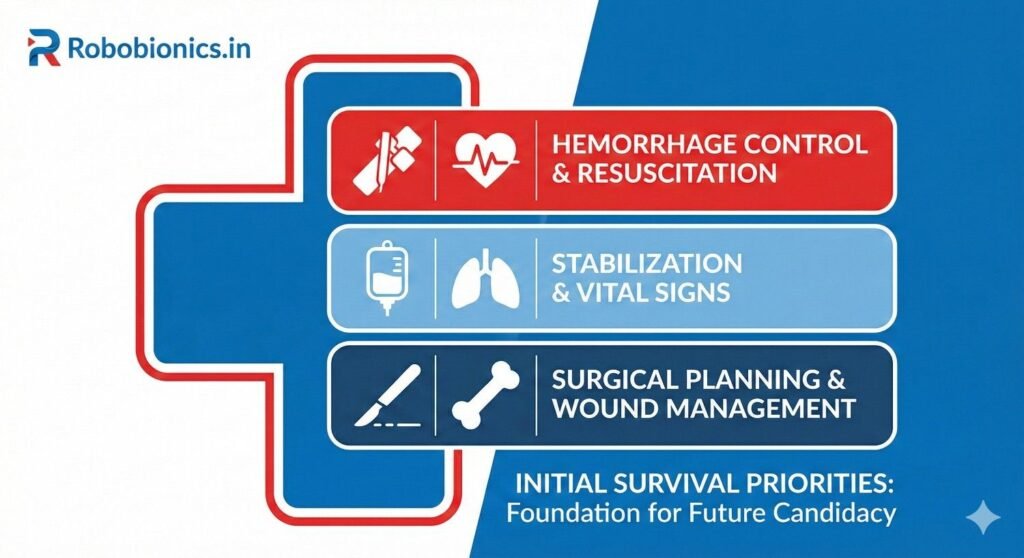

In trauma care, saving life always comes before saving limb or planning mobility.

Until bleeding, infection risk, and organ injury are controlled, prosthetic planning must wait.

A stable patient is the foundation of safe prosthetic candidacy.

Many trauma amputees also have head injuries, chest trauma, or fractures in other limbs.

Each of these injuries affects when and how rehabilitation can begin.

Prosthetic planning must account for the slowest healing system in the body.

Long ICU stays often lead to muscle loss, joint stiffness, and fatigue.

These issues reduce early prosthetic tolerance even if the amputation site heals well.

Recognizing ICU-related weakness helps set realistic early goals.

Clean bone cuts, well-shaped muscle coverage, and good skin closure improve future prosthetic fit.

Emergency trauma surgeries may not always achieve ideal shapes due to time pressure.

Later revision surgery may be needed before prosthetic fitting is considered.

Higher levels of amputation demand more energy and balance during prosthetic use.

Severe trauma often causes loss of muscle and soft tissue beyond the bone level.

These losses directly affect control, comfort, and long-term wear.

Plates, rods, or fragments may cause pain under load.

If these issues are not addressed early, prosthetic use can become painful or unsafe.

Imaging and surgical review are essential before final candidacy decisions.

Trauma wounds are often contaminated and crushed, not cleanly cut.

This increases the risk of delayed healing and deep infection.

Prosthetic candidacy should only be considered once infection risk is clearly controlled.

Closed skin alone is not enough to confirm readiness.

The limb should tolerate gentle pressure, movement, and daily handling without pain or redness.

Stable healing over time matters more than quick closure.

Skin grafts and large scars behave differently under pressure.

They may need special socket design and slower load increase.

These factors should shape the candidacy timeline, not exclude the patient.

Early pain is expected after trauma and surgery.

Persistent or worsening pain needs investigation before prosthetic planning.

Uncontrolled pain blocks learning and reduces trust in the device.

Trauma often damages nerves in irregular ways.

Burning, shooting, or electric pain suggests nerve involvement.

These patterns require targeted treatment before prosthetic training.

Phantom pain is common after trauma and does not exclude prosthetic use.

However, severe phantom pain can reduce tolerance and focus.

Early education and pain management improve later candidacy.

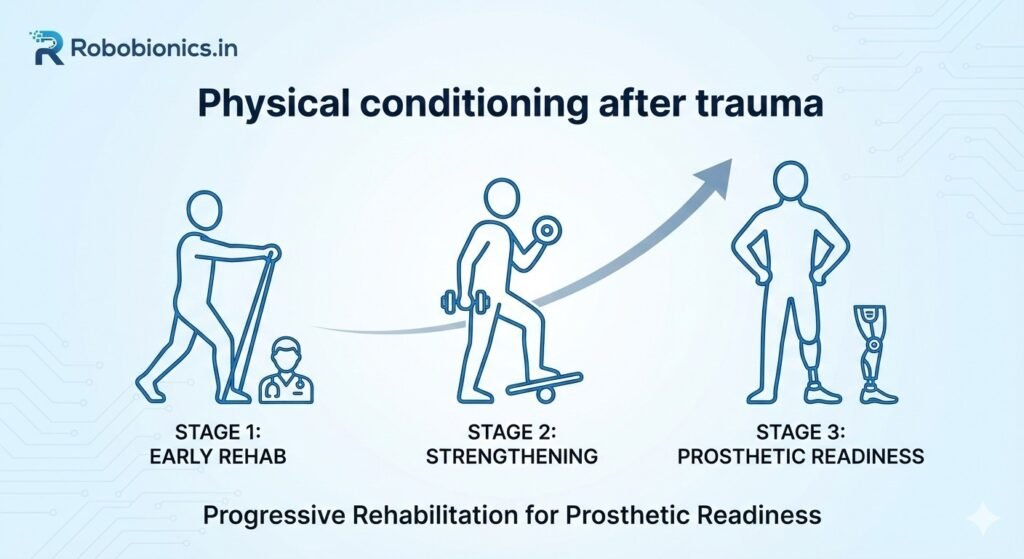

Even young trauma patients lose strength quickly during bed rest.

Weakness in the core and hips affects balance and control.

Pre-prosthetic strengthening is often needed before fitting.

Immobilization after trauma increases the risk of stiff joints.

Hip and knee stiffness can severely limit prosthetic walking.

Early movement and positioning reduce this risk.

Reduced activity lowers stamina and exercise tolerance.

Prosthetic walking increases energy demand, especially above the knee.

Fitness level should be considered when judging readiness.

Even mild head injury can affect focus and reaction time.

These changes increase fall risk during prosthetic training.

Candidacy decisions must include cognitive screening.

Learning to walk with a prosthesis requires repeated practice and recall.

Memory problems can slow progress and frustrate patients.

Training plans should adjust pace rather than deny care.

Some trauma patients underestimate risk due to emotional or brain-related changes.

This can lead to unsafe behavior during early walking.

Clear boundaries and supervision are essential.

Trauma amputation happens without warning and often causes deep emotional distress.

Patients may appear calm while still processing loss internally.

Emotional readiness is as important as physical healing.

Flashbacks, anxiety, and fear of re-injury are common after severe trauma.

These symptoms can interfere with training and confidence.

Early recognition allows timely mental health support.

Some patients push themselves to walk too fast to prove recovery.

Others feel pressure from family or society to return to normal quickly.

Balanced motivation leads to safer and more sustainable outcomes.

Families also experience trauma and may struggle to adapt.

Their fear can either protect or limit the patient.

Including them in discussions improves cooperation.

Trauma often interrupts income suddenly.

Financial stress can push patients to rush prosthetic use.

Clear planning helps align recovery with long-term stability.

Patients with strong social support recover better.

Isolation increases dropout and depression.

Support systems should be considered part of candidacy.

We have now covered the early and mid-stage clinical criteria that shape prosthetic candidacy after trauma amputation, focusing on surgery, healing, pain, physical conditioning, cognition, and emotional readiness.

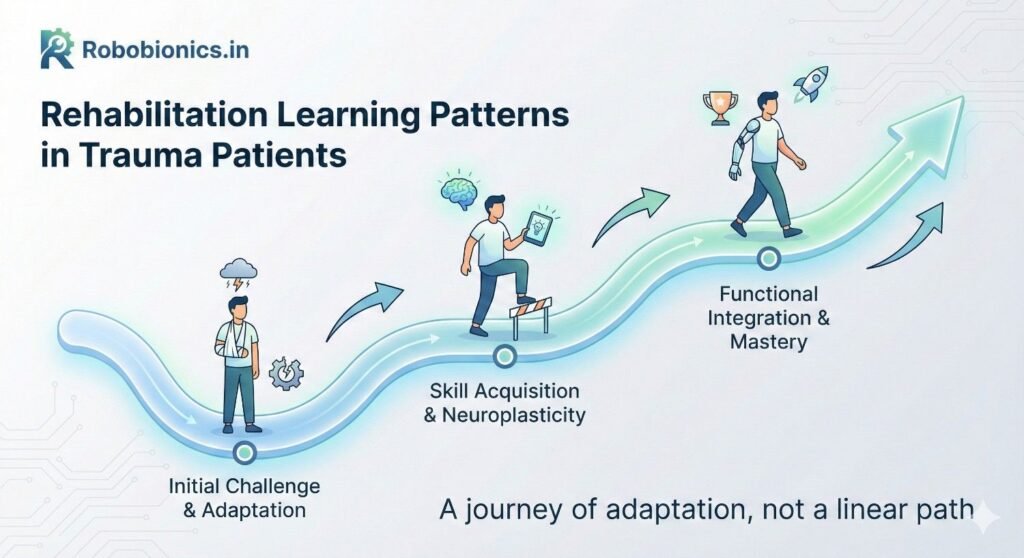

In trauma amputation, the body may heal faster than the mind, or the mind may be ready before the body can safely respond.

Choosing the right time for prosthetic progression is not about dates on a calendar but about observing stable patterns in healing, strength, and behavior.

Poor timing is one of the most common reasons for early prosthetic failure in trauma patients.

The residual limb should show stable volume, healthy skin response, and tolerance to gentle pressure over repeated days.

Pain should be controlled enough that the patient can focus on learning rather than coping.

Transfers, sitting balance, and supported standing should feel safe and repeatable.

Repeated skin irritation, increasing pain, or rapid fatigue suggest the body is not yet ready.

Emotional distress, confusion, or poor safety awareness are also valid reasons to delay.

Waiting in these cases protects trust and long-term success rather than slowing recovery.

After trauma, many patients lose confidence in their own body.

Pre-prosthetic rehab helps them relearn safe movement and control before adding a prosthesis.

This step reduces fear and improves cooperation during later training.

Lower-limb prosthetic use depends heavily on trunk and hip control.

Trauma patients often have weakness from bed rest or injury-related guarding.

Targeted strengthening prepares the body to accept new movement patterns.

The non-amputated leg carries extra load during early prosthetic use.

If it is weak or painful, progress slows and injury risk rises.

Strengthening and protecting the sound limb is a key candidacy factor.

The first trial is not about walking far or looking normal.

Its purpose is to test comfort, safety, and emotional response under controlled conditions.

Clear explanation before the trial prevents disappointment and fear.

Watch how the patient stands, shifts weight, and responds to pressure.

Guarding, grimacing, or rapid fatigue offer valuable information.

These signs guide immediate adjustment or delay.

Some trauma patients feel joy when standing again, while others feel panic or grief.

Both responses are normal and informative.

Emotional readiness should be respected as part of candidacy.

Some trauma patients learn quickly due to youth and fitness.

Others move slowly because of fear or pain memory.

Both patterns can succeed when training is matched to learning style.

Impatience is common in trauma survivors who want life to return to normal.

Clear milestones help channel this energy safely.

Unmanaged impatience increases injury risk.

Learning new walking patterns is mentally demanding.

Trauma patients may tire mentally before they tire physically.

Short, focused sessions often work better than long ones.

Lack of progress does not always mean poor candidacy.

It often reflects pain, fear, or unclear expectations.

Reassessment helps identify the true barrier.

Poor fit, alignment, or component choice can mimic patient failure.

Before judging candidacy, technical factors must be reviewed carefully.

This protects patients from unfair conclusions.

Sometimes the safest choice is to pause training briefly.

Explaining this clearly maintains trust and motivation.

Ethical care values long-term outcomes over speed.

Patients who integrate the prosthesis into daily life early tend to succeed long term.

Inconsistent use often signals unresolved comfort or emotional issues.

Monitoring wear patterns offers early insight.

Clinic walking does not guarantee outdoor success.

Trauma patients must adapt to uneven ground, crowds, and distractions.

Gradual exposure builds confidence and safety.

Emotional healing continues long after physical recovery.

Changes in mood or confidence may appear months later.

Regular check-ins help sustain long-term use.

Some patients need more time for healing, strength, or emotional processing.

Clear guidance on what must improve keeps hope realistic.

Temporary delay is part of good care.

Severe brain injury, uncontrolled pain, or repeated unsafe behavior may limit prosthetic use.

These cases require honest discussion and alternative mobility planning.

Protecting safety is always the priority.

Even without a prosthesis, patients can live full and independent lives.

Respectful communication preserves trust and self-worth.

Mobility options should match the person, not an ideal image.

Doctors are often seen as final decision-makers.

In trauma care, guiding patients through readiness is more effective than issuing approval.

This approach builds partnership and adherence.

Trauma patients and families value clarity during uncertainty.

Simple explanations reduce fear and unrealistic expectations.

Good communication is a clinical skill that shapes outcomes.

Surgeons, rehab doctors, therapists, and prosthetists must work as one unit.

Clear roles and shared goals prevent confusion.

Team alignment strengthens candidacy decisions.

Walking safely and independently matters more than how the limb looks.

Trauma patients often worry about public perception.

Redirecting focus to function improves satisfaction.

Using the prosthesis for real tasks defines success.

Transfers, self-care, and community mobility matter most.

These outcomes reflect proper selection and timing.

Good candidacy decisions reduce joint damage, falls, and chronic pain.

This long-term view protects both patient and healthcare system.

Trauma care does not end at discharge.

Trauma amputation demands patience, structure, and compassion.

Prosthetic candidacy is not a single moment but a process that evolves with healing and confidence.

When doctors respect timing, readiness, and the human experience of trauma, prosthetics become tools for recovery rather than reminders of loss.

Many trauma patients appear physically capable early, which can push teams to move faster than the body or mind can handle.

Strength alone does not equal readiness, and early pressure often leads to pain, fear, or dropout.

Slowing down at the right time protects long-term outcomes.

Emotional trauma is less visible than wounds but just as real.

When fear, anger, or grief are not addressed, prosthetic use often suffers.

Acknowledging emotions improves cooperation and trust.

Slow progress is often a signal, not a verdict.

Adjusting timing, training, or expectations usually restores momentum.

Labeling a patient too early causes unnecessary harm.

Doctors must protect patients from unsafe optimism while preserving hope.

Clear explanations help patients accept delays without losing motivation.

Ethical care chooses the right time, not the fastest path.

Patients should be involved in decisions even when they are not ready yet.

Understanding the reasons behind clinical choices builds respect.

Shared decisions reduce conflict and regret.

When prosthetic use is not possible or must be delayed, alternatives should be presented respectfully.

Wheelchairs, aids, and environmental changes can still support independence.

Dignity must never depend on a device.

Younger trauma patients often aim to return to full activity quickly.

Guided pacing helps convert ambition into sustainable progress.

Clear milestones reduce frustration.

Long admissions often slow physical and emotional recovery.

These patients benefit from extended pre-prosthetic rehab.

Patience at this stage pays off later.

Distance, terrain, and limited follow-up affect outcomes.

Simpler, durable solutions often work best.

Context-aware decisions matter.

At Robobionics, we work closely with doctors who guide trauma amputees through some of the most difficult transitions of their lives.

We have seen that successful prosthetic use after trauma depends less on speed and more on timing, trust, and thoughtful selection.

By respecting clinical criteria and the human experience of injury, prosthetics can support recovery with safety, dignity, and lasting confidence.

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

For trauma amputees, the journey does not begin at the prosthetic clinic. It begins much

Amputation after cancer is not just a surgical event. It is the end of one

When a child loses a limb, the challenge is never only physical. A child’s body

Last updated: November 10, 2022

Thank you for shopping at Robo Bionics.

If, for any reason, You are not completely satisfied with a purchase We invite You to review our policy on refunds and returns.

The following terms are applicable for any products that You purchased with Us.

The words of which the initial letter is capitalized have meanings defined under the following conditions. The following definitions shall have the same meaning regardless of whether they appear in singular or in plural.

For the purposes of this Return and Refund Policy:

Company (referred to as either “the Company”, “Robo Bionics”, “We”, “Us” or “Our” in this Agreement) refers to Bionic Hope Private Limited, Pearl Haven, 1st Floor Kumbharwada, Manickpur Near St. Michael’s Church Vasai Road West, Palghar Maharashtra 401202.

Goods refer to the items offered for sale on the Website.

Orders mean a request by You to purchase Goods from Us.

Service refers to the Services Provided like Online Demo and Live Demo.

Website refers to Robo Bionics, accessible from https://robobionics.in

You means the individual accessing or using the Service, or the company, or other legal entity on behalf of which such individual is accessing or using the Service, as applicable.

You are entitled to cancel Your Service Bookings within 7 days without giving any reason for doing so, before completion of Delivery.

The deadline for cancelling a Service Booking is 7 days from the date on which You received the Confirmation of Service.

In order to exercise Your right of cancellation, You must inform Us of your decision by means of a clear statement. You can inform us of your decision by:

We will reimburse You no later than 7 days from the day on which We receive your request for cancellation, if above criteria is met. We will use the same means of payment as You used for the Service Booking, and You will not incur any fees for such reimbursement.

Please note in case you miss a Service Booking or Re-schedule the same we shall only entertain the request once.

In order for the Goods to be eligible for a return, please make sure that:

The following Goods cannot be returned:

We reserve the right to refuse returns of any merchandise that does not meet the above return conditions in our sole discretion.

Only regular priced Goods may be refunded by 50%. Unfortunately, Goods on sale cannot be refunded. This exclusion may not apply to You if it is not permitted by applicable law.

You are responsible for the cost and risk of returning the Goods to Us. You should send the Goods at the following:

We cannot be held responsible for Goods damaged or lost in return shipment. Therefore, We recommend an insured and trackable courier service. We are unable to issue a refund without actual receipt of the Goods or proof of received return delivery.

If you have any questions about our Returns and Refunds Policy, please contact us:

Last Updated on: 1st Jan 2021

These Terms and Conditions (“Terms”) govern Your access to and use of the website, platforms, applications, products and services (ively, the “Services”) offered by Robo Bionics® (a registered trademark of Bionic Hope Private Limited, also used as a trade name), a company incorporated under the Companies Act, 2013, having its Corporate office at Pearl Heaven Bungalow, 1st Floor, Manickpur, Kumbharwada, Vasai Road (West), Palghar – 401202, Maharashtra, India (“Company”, “We”, “Us” or “Our”). By accessing or using the Services, You (each a “User”) agree to be bound by these Terms and all applicable laws and regulations. If You do not agree with any part of these Terms, You must immediately discontinue use of the Services.

1.1 “Individual Consumer” means a natural person aged eighteen (18) years or above who registers to use Our products or Services following evaluation and prescription by a Rehabilitation Council of India (“RCI”)–registered Prosthetist.

1.2 “Entity Consumer” means a corporate organisation, nonprofit entity, CSR sponsor or other registered organisation that sponsors one or more Individual Consumers to use Our products or Services.

1.3 “Clinic” means an RCI-registered Prosthetics and Orthotics centre or Prosthetist that purchases products and Services from Us for fitment to Individual Consumers.

1.4 “Platform” means RehabConnect™, Our online marketplace by which Individual or Entity Consumers connect with Clinics in their chosen locations.

1.5 “Products” means Grippy® Bionic Hand, Grippy® Mech, BrawnBand™, WeightBand™, consumables, accessories and related hardware.

1.6 “Apps” means Our clinician-facing and end-user software applications supporting Product use and data collection.

1.7 “Impact Dashboard™” means the analytics interface provided to CSR, NGO, corporate and hospital sponsors.

1.8 “Services” includes all Products, Apps, the Platform and the Impact Dashboard.

2.1 Individual Consumers must be at least eighteen (18) years old and undergo evaluation and prescription by an RCI-registered Prosthetist prior to purchase or use of any Products or Services.

2.2 Entity Consumers must be duly registered under the laws of India and may sponsor one or more Individual Consumers.

2.3 Clinics must maintain valid RCI registration and comply with all applicable clinical and professional standards.

3.1 Robo Bionics acts solely as an intermediary connecting Users with Clinics via the Platform. We do not endorse or guarantee the quality, legality or outcomes of services rendered by any Clinic. Each Clinic is solely responsible for its professional services and compliance with applicable laws and regulations.

4.1 All content, trademarks, logos, designs and software on Our website, Apps and Platform are the exclusive property of Bionic Hope Private Limited or its licensors.

4.2 Subject to these Terms, We grant You a limited, non-exclusive, non-transferable, revocable license to use the Services for personal, non-commercial purposes.

4.3 You may not reproduce, modify, distribute, decompile, reverse engineer or create derivative works of any portion of the Services without Our prior written consent.

5.1 Limited Warranty. We warrant that Products will be free from workmanship defects under normal use as follows:

(a) Grippy™ Bionic Hand, BrawnBand® and WeightBand®: one (1) year from date of purchase, covering manufacturing defects only.

(b) Chargers and batteries: six (6) months from date of purchase.

(c) Grippy Mech™: three (3) months from date of purchase.

(d) Consumables (e.g., gloves, carry bags): no warranty.

5.2 Custom Sockets. Sockets fabricated by Clinics are covered only by the Clinic’s optional warranty and subject to physiological changes (e.g., stump volume, muscle sensitivity).

5.3 Exclusions. Warranty does not apply to damage caused by misuse, user negligence, unauthorised repairs, Acts of God, or failure to follow the Instruction Manual.

5.4 Claims. To claim warranty, You must register the Product online, provide proof of purchase, and follow the procedures set out in the Warranty Card.

5.5 Disclaimer. To the maximum extent permitted by law, all other warranties, express or implied, including merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, are disclaimed.

6.1 We collect personal contact details, physiological evaluation data, body measurements, sensor calibration values, device usage statistics and warranty information (“User Data”).

6.2 User Data is stored on secure servers of our third-party service providers and transmitted via encrypted APIs.

6.3 By using the Services, You consent to collection, storage, processing and transfer of User Data within Our internal ecosystem and to third-party service providers for analytics, R&D and support.

6.4 We implement reasonable security measures and comply with the Information Technology Act, 2000, and Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

6.5 A separate Privacy Policy sets out detailed information on data processing, user rights, grievance redressal and cross-border transfers, which forms part of these Terms.

7.1 Pursuant to the Information Technology Rules, 2021, We have given the Charge of Grievance Officer to our QC Head:

- Address: Grievance Officer

- Email: support@robobionics.in

- Phone: +91-8668372127

7.2 All support tickets and grievances must be submitted exclusively via the Robo Bionics Customer Support portal at https://robobionics.freshdesk.com/.

7.3 We will acknowledge receipt of your ticket within twenty-four (24) working hours and endeavour to resolve or provide a substantive response within seventy-two (72) working hours, excluding weekends and public holidays.

8.1 Pricing. Product and Service pricing is as per quotations or purchase orders agreed in writing.

8.2 Payment. We offer (a) 100% advance payment with possible incentives or (b) stage-wise payment plans without incentives.

8.3 Refunds. No refunds, except pro-rata adjustment where an Individual Consumer is medically unfit to proceed or elects to withdraw mid-stage, in which case unused stage fees apply.

9.1 Users must follow instructions provided by RCI-registered professionals and the User Manual.

9.2 Users and Entity Consumers shall indemnify and hold Us harmless from all liabilities, claims, damages and expenses arising from misuse of the Products, failure to follow professional guidance, or violation of these Terms.

10.1 To the extent permitted by law, Our total liability for any claim arising out of or in connection with these Terms or the Services shall not exceed the aggregate amount paid by You to Us in the twelve (12) months preceding the claim.

10.2 We shall not be liable for any indirect, incidental, consequential or punitive damages, including loss of profit, data or goodwill.

11.1 Our Products are classified as “Rehabilitation Aids,” not medical devices for diagnostic purposes.

11.2 Manufactured under ISO 13485:2016 quality management and tested for electrical safety under IEC 60601-1 and IEC 60601-1-2.

11.3 Products shall only be used under prescription and supervision of RCI-registered Prosthetists, Physiotherapists or Occupational Therapists.

We do not host third-party content or hardware. Any third-party services integrated with Our Apps are subject to their own terms and privacy policies.

13.1 All intellectual property rights in the Services and User Data remain with Us or our licensors.

13.2 Users grant Us a perpetual, irrevocable, royalty-free licence to use anonymised usage data for analytics, product improvement and marketing.

14.1 We may amend these Terms at any time. Material changes shall be notified to registered Users at least thirty (30) days prior to the effective date, via email and website notice.

14.2 Continued use of the Services after the effective date constitutes acceptance of the revised Terms.

Neither party shall be liable for delay or failure to perform any obligation under these Terms due to causes beyond its reasonable control, including Acts of God, pandemics, strikes, war, terrorism or government regulations.

16.1 All disputes shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

16.2 A sole arbitrator shall be appointed by Bionic Hope Private Limited or, failing agreement within thirty (30) days, by the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration.

16.3 Seat of arbitration: Mumbai, India.

16.4 Governing law: Laws of India.

16.5 Courts at Mumbai have exclusive jurisdiction over any proceedings to enforce an arbitral award.

17.1 Severability. If any provision is held invalid or unenforceable, the remainder shall remain in full force.

17.2 Waiver. No waiver of any breach shall constitute a waiver of any subsequent breach of the same or any other provision.

17.3 Assignment. You may not assign your rights or obligations without Our prior written consent.

By accessing or using the Products and/or Services of Bionic Hope Private Limited, You acknowledge that You have read, understood and agree to be bound by these Terms and Conditions.