Post-Op Follow-Up Schedule That Prevents Prosthetic Delays (For Clinicians)

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

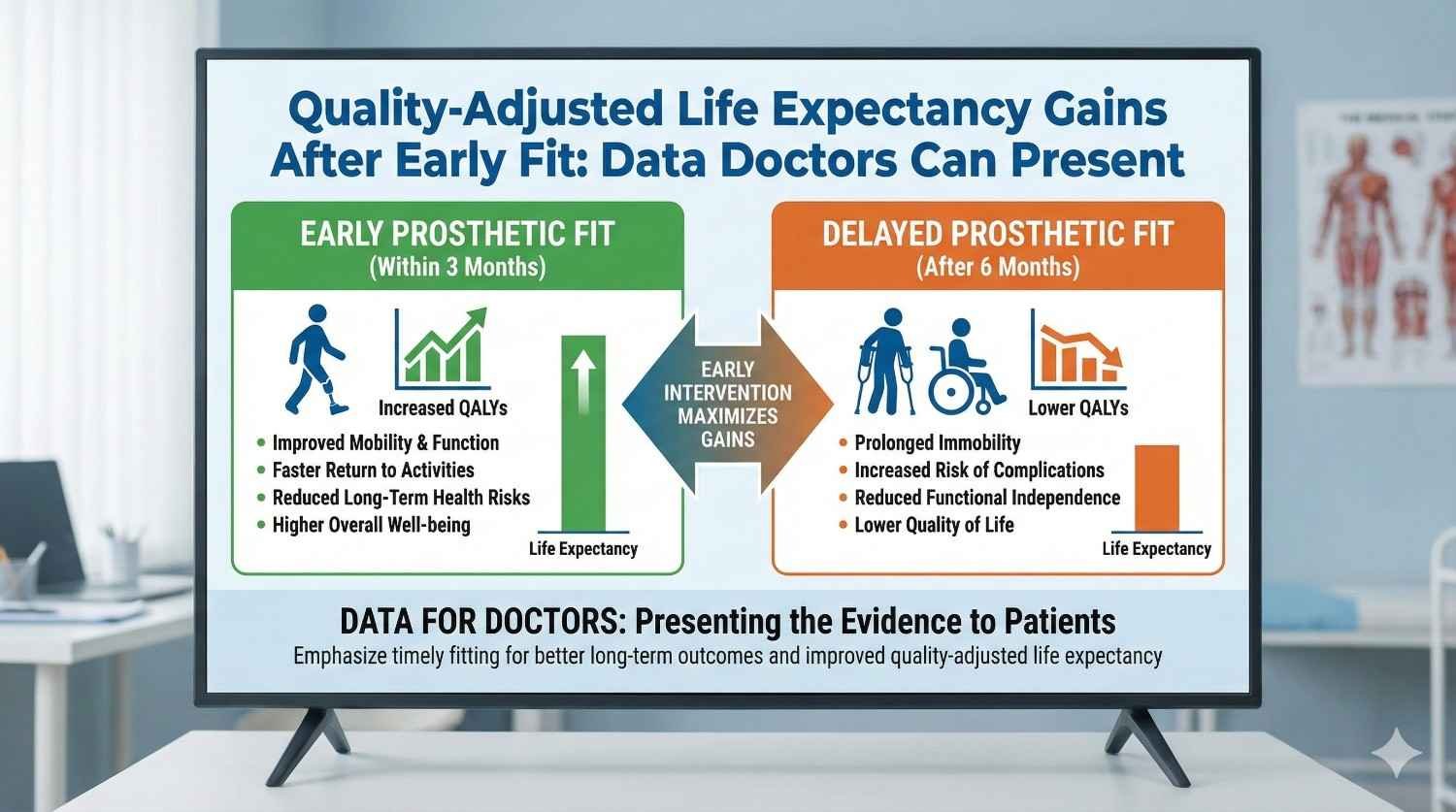

When doctors talk about early prosthetic fitting, they often rely on experience and intuition. They know patients do better, move sooner, and feel more confident. Yet in many clinical, insurance, or hospital discussions, intuition is not enough. Decision-makers ask for data. They ask how early fitting changes not just mobility, but life itself. This article explains, in very simple terms, how early prosthetic fitting improves quality-adjusted life expectancy, what that actually means for patients, and how doctors can present this data clearly and confidently in real-world settings.

In medical practice, survival is often the easiest outcome to measure.

Either a patient lives longer or they do not.

However, in prosthetic care, survival alone says very little about whether life is lived fully or with constant limitation.

Quality-adjusted life expectancy combines two ideas that matter deeply to patients.

The first is how long they live.

The second is how well they live during that time.

It recognizes that ten years with independence, movement, and dignity are not the same as ten years with pain, isolation, or dependency.

For amputees, this distinction is critical.

A prosthesis does not usually change how long someone lives in a direct way.

It changes how active, independent, and socially engaged those years are.

That is where early fitting shows its strongest impact.

Quality adjustment works by assigning a value to health states.

Perfect health is usually considered one.

States with pain, limitation, or dependency score lower.

For example, a person who walks independently, works, and participates socially scores much higher than someone who avoids movement, depends on others, and limits daily activity.

When these scores are combined with time, doctors can describe gains in quality-adjusted life expectancy.

This may sound abstract, but the idea is simple.

Early fitting helps patients spend more years in better health states.

Late fitting often traps patients in poorer states for longer periods, even if they eventually receive a prosthesis.

Doctors often struggle to explain why timing matters so much.

Patients, families, and payers may see early fitting as optional or cosmetic.

Quality-adjusted life expectancy gives doctors a structured way to explain long-term impact.

Instead of arguing that early fitting feels better, doctors can show that it changes the trajectory of life itself.

It shifts years from low-quality living to higher-quality living.

This framing is powerful because it aligns clinical judgment with measurable outcomes.

After amputation, the body and mind enter a period of rapid change.

Muscles weaken quickly if unused.

Balance strategies adapt to loss.

Confidence either grows or collapses based on early experiences.

Early fitting takes advantage of this window.

It allows patients to relearn movement before harmful compensations set in.

It prevents long periods of inactivity that reduce physical capacity and motivation.

When fitting is delayed, patients often adapt to life without a prosthesis.

These adaptations are hard to reverse later.

Even when a device is finally introduced, usage may remain limited.

Early fitting does more than restore movement.

It restores identity.

Patients who stand, walk, or grasp early begin to see themselves as capable again.

This psychological momentum influences every future decision.

Patients are more likely to return to work, engage in therapy, and invest effort.

These behaviors accumulate over time into better quality-adjusted outcomes.

Late fitting often forces patients to rebuild identity from a place of loss and frustration.

This takes longer and is less complete.

The difference may not appear dramatic in the first year, but it compounds across decades.

Prosthetic use is a habit, not a switch.

Habits form fastest when new routines are built early.

Early fitting integrates the prosthesis into daily life before avoidance patterns develop.

Patients learn to reach for the device automatically.

This leads to higher daily use and better functional ceilings.

Late fitting often results in selective use.

Patients wear the prosthesis only for special tasks.

Lower use translates into lower quality-adjusted life over time.

Across many studies and clinical datasets, earlier fitting is linked to higher functional scores.

Patients walk longer distances, perform more tasks, and report less fatigue.

These gains are not limited to the first year.

Patients who start strong tend to maintain higher function later.

This persistence is key to quality-adjusted life expectancy.

Even small functional differences early can translate into large differences over decades.

Climbing stairs, commuting independently, or standing at work shape daily life quality.

Delayed mobility often leads to secondary problems such as back pain, joint strain, and cardiovascular deconditioning.

These problems lower quality scores even if the prosthesis itself functions well later.

Early fitting keeps patients active during recovery.

This preserves muscle strength, balance, and overall fitness.

By preventing secondary issues, early fitting protects future years from decline.

This protective effect is often underestimated but strongly influences long-term quality.

Employment and social participation are major contributors to quality-adjusted life.

Data consistently shows that patients fitted earlier return to work sooner and stay employed longer.

Work is not just income.

It is structure, social connection, and self-worth.

Early fitting shortens the gap between injury and reintegration.

Shorter gaps mean fewer lost opportunities and stronger long-term outcomes.

When doctors calculate quality-adjusted life expectancy gains, they are not claiming that early fitting adds years to life.

They are showing that it improves the quality of years already expected.

For example, if a patient is expected to live forty more years after amputation, the question becomes how many of those years are lived independently versus dependently.

Early fitting shifts more of those years into higher-quality states.

Even modest improvements in annual quality scores, when multiplied by decades, result in meaningful gains.

This is the core argument doctors can present.

A quality improvement of even 0.05 per year may seem small.

But over forty years, this becomes two full quality-adjusted life years.

Two years of full-quality living is not a minor benefit.

It represents years of independence, productivity, and dignity.

Doctors should emphasize this accumulation effect.

Early fitting is an investment whose returns compound quietly over time.

In delayed fitting scenarios, patients may spend the first several years in very low-quality states.

Even if quality improves later, those lost years cannot be recovered.

Early fitting raises the baseline immediately.

Patients start their post-amputation life at a higher level of function and confidence.

When plotted over time, the area under the curve is clearly larger for early fitting.

This visual explanation is often effective in presentations.

Most audiences do not need formulas.

They need stories grounded in data.

Doctors can describe two patient journeys side by side.

One fitted early, one fitted late.

Then explain how daily life differs over years.

By anchoring data in lived experience, the concept becomes intuitive.

Numbers support the story rather than replace it.

Early fitting should be framed as reducing long-term risk, not as adding short-term cost.

The risk is years of low-quality life, secondary health issues, and reduced participation.

Quality-adjusted life expectancy gives language to this risk.

It shows what is lost when fitting is delayed.

Risk framing resonates with hospitals, insurers, and families.

It shifts the discussion from expense to prevention.

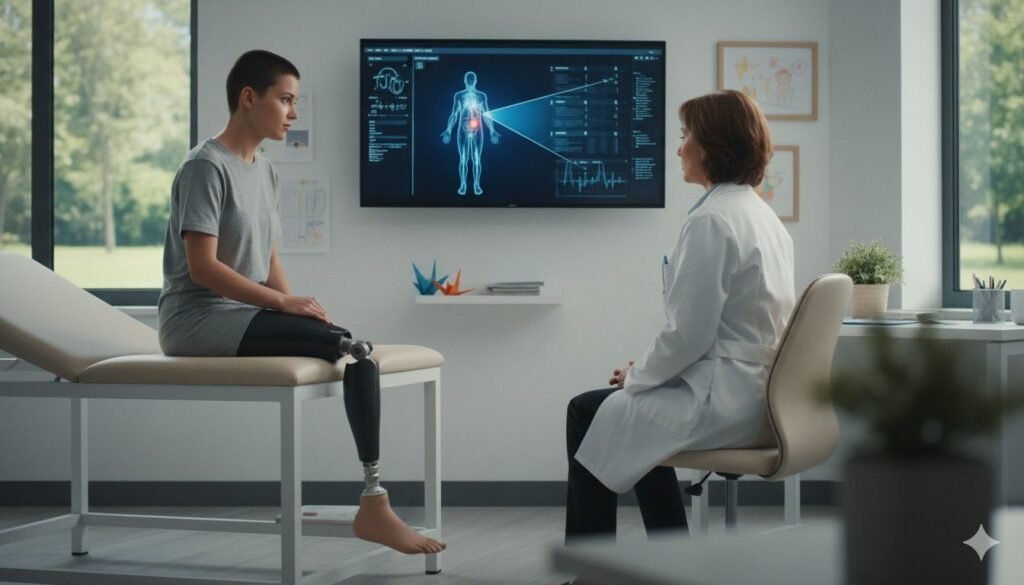

Patients care about walking, working, and participating.

Doctors should link quality-adjusted outcomes to these goals.

Instead of saying early fitting improves scores, doctors can say it increases the chance of staying active across adulthood.

This translation makes data meaningful.

When patients see their future reflected in the data, decisions become easier.

Mobility is often the most visible benefit of early prosthetic fitting, but its deeper impact is endurance and confidence rather than speed alone. When patients begin walking early, their cardiovascular system stays active, muscles retain strength, and balance strategies develop around the prosthesis instead of around avoidance. This allows walking to feel normal rather than exhausting, which strongly affects how often patients choose to move in daily life.

Patients who start late often regain the ability to walk but avoid longer distances because fatigue sets in quickly. Over years, this avoidance reduces overall activity levels and slowly lowers quality of life. Early fitting protects walking endurance, which quietly improves the quality score of almost every day that follows.

When patients remain without a prosthesis for long periods, the body adapts in ways that are hard to reverse. Limping, overloading the sound limb, and poor posture become habits. These habits may allow short-term function but reduce long-term comfort and safety.

Early fitting reduces the time available for these patterns to form. Patients learn symmetrical movement earlier and protect joints from uneven stress. Over decades, this prevention translates into fewer pain-related limitations and a higher quality-adjusted life expectancy, even if these benefits are not immediately obvious.

As patients age, balance and strength naturally decline. Those who have used a prosthesis confidently for years adapt more easily to these changes. Their nervous system is familiar with the device, and adjustments feel manageable rather than threatening.

Patients who start late often face a double challenge as they age. They must adapt to both the prosthesis and age-related changes at the same time. This increases fall risk and dependency, lowering quality scores in later life. Early fitting spreads adaptation over time and protects quality in older age.

Amputation is not only a physical loss. It is an emotional rupture. Early fitting helps shorten the period during which patients feel helpless or incomplete. Regaining function early allows the mind to shift from loss to adaptation.

Patients fitted late often spend months or years focused on what they cannot do. Even after fitting, this emotional weight can persist and limit engagement. Early fitting interrupts this cycle sooner, leading to better long-term emotional stability and higher quality-adjusted outcomes.

Self-efficacy, the belief that one can influence outcomes, is a strong predictor of long-term quality of life. Early fitting gives patients quick feedback that effort leads to progress. This reinforces a sense of control.

Patients who feel in control are more likely to stay active, seek help when needed, and adapt to challenges. Over time, these behaviors compound into better mental health and higher quality-adjusted life expectancy. Late fitting often delays this learning and weakens its impact.

While early fitting does not eliminate emotional distress, data consistently shows lower long-term depression and anxiety rates in patients who regain function sooner. Being able to move, work, and participate socially acts as a buffer against chronic low mood.

Mental health affects quality scores every single day. Even small reductions in persistent anxiety or sadness can significantly raise cumulative quality-adjusted life over decades. This is an important point doctors can emphasize when discussing timing.

Within families, amputation often changes roles suddenly. Patients may shift from contributors to dependents overnight. Early fitting helps reverse this shift sooner.

When patients resume basic household tasks or caregiving roles early, family dynamics stabilize faster. This reduces long-term emotional strain on both patients and caregivers. Stronger relationships directly improve quality of life and reduce isolation, which is a major driver of low quality scores.

Social withdrawal is common after amputation, especially when mobility is limited. Early fitting reduces the period of withdrawal and helps patients stay connected to friends, neighbors, and community activities.

Maintained social networks protect mental health and encourage activity. Over time, this social continuity increases quality-adjusted life expectancy by reducing loneliness and inactivity. Late fitting often leads to social circles shrinking permanently.

Being able to move confidently in public affects how patients see themselves. Early fitting allows patients to practice public movement sooner, reducing embarrassment and fear.

This comfort in public spaces supports participation in markets, workplaces, and events. These everyday interactions may seem small, but they define the lived quality of life. Early fitting increases the number of days lived with dignity rather than avoidance.

Work plays a central role in quality-adjusted life, not only through income but through structure and purpose. Early fitting shortens the time between amputation and return to work.

Even partial or modified work early helps patients maintain skills and professional identity. Over years, this leads to higher lifetime earnings and financial stability, which strongly influence life quality. Late fitting often leads to prolonged absence and permanent income loss.

For younger patients, timing affects entire career paths. Delayed fitting may force job changes or early exit from skilled roles. Early fitting increases the chance of resuming previous work or transitioning smoothly.

This protection of career trajectory has long-term effects on self-esteem, financial security, and family well-being. When doctors frame early fitting in these terms, quality-adjusted life expectancy becomes a concrete concept rather than an abstract metric.

Financial dependency on family or support systems lowers perceived quality of life. Early fitting reduces the duration and intensity of this dependency.

Patients who regain earning capacity earlier report higher life satisfaction even years later. This sustained independence raises quality scores across adulthood. Late fitting often leaves a lasting sense of burden that affects mental well-being.

Patients who remain inactive or use prostheses poorly are more likely to develop complications that require medical attention. These visits disrupt life and reinforce a sense of fragility.

Early fitting reduces inactivity and improves device use, lowering complication rates over time. Fewer hospital visits mean more uninterrupted days of normal living, which increases quality-adjusted life expectancy in a very practical way.

Early fitting increases motivation for rehab because progress is visible. Patients see how exercises translate into real-world function.

Better rehab engagement improves long-term outcomes and reduces the need for repeated interventions. This efficiency benefits both patients and health systems, but more importantly, it preserves patient time and energy, which directly affects quality of life.

Patients who experience early success tend to maintain positive relationships with care teams. They seek help early when issues arise and avoid crises.

This proactive care pattern reduces stress and improves outcomes over time. The quality-adjusted benefit comes from stability and predictability rather than dramatic interventions.

When doctors speak to hospital committees, the discussion often revolves around efficiency, outcomes, and reputation. Early prosthetic fitting should be presented as a quality intervention rather than a timing preference. Hospitals understand that early mobilization in surgery improves outcomes, and the same logic applies here.

Doctors can explain that early fitting reduces long-term complications, repeat visits, and prolonged rehab cycles. These improvements protect hospital resources and improve reported outcomes. Quality-adjusted life expectancy becomes a way to show that early fitting improves the value delivered per patient over time, which aligns with hospital performance goals.

Hospitals are also sensitive to patient satisfaction and word-of-mouth. Early success stories shape perception. Patients who regain function quickly speak positively about care, while those who struggle early often carry dissatisfaction forward. Framing early fitting as a driver of long-term patient experience makes the data relevant to administrators.

Insurers focus on risk, cost predictability, and long-term liability. Doctors should avoid presenting early fitting as an added expense and instead describe it as a risk-reduction strategy. Delayed fitting increases the likelihood of secondary health problems, device underuse, and repeated claims.

Quality-adjusted life expectancy allows doctors to explain that early fitting shifts patients into higher-functioning states for longer periods. Higher-functioning patients use fewer health services over time. Even if early fitting requires upfront investment, it reduces cumulative cost exposure.

Using time-based comparisons helps. Doctors can describe how a patient fitted early may avoid years of low-function living that often leads to medical and psychological claims. This approach aligns with insurer logic and reframes early fitting as prudent planning.

Families often worry about immediate cost and visible risk. They may see early fitting as rushed or unnecessary. Doctors should translate quality-adjusted life concepts into everyday terms that families relate to.

Instead of discussing scores, doctors can describe how early fitting increases the number of years a patient remains active, independent, and socially engaged. Families understand what it means to have a parent who can work, move, and participate without constant help.

When families see that early fitting protects future independence rather than just restoring movement, their support increases. This shared understanding improves adherence and reduces conflict during care.

One effective way to explain quality-adjusted life expectancy is to describe two life trajectories. Both patients live the same number of years, but their experiences differ. One spends the early years after amputation inactive and dependent, while the other regains function early and stays active longer.

Doctors can explain that even if both patients eventually use a prosthesis, the early years cannot be recovered. Those years shape habits, confidence, and health. Visualizing this difference helps audiences understand why timing matters so much.

This narrative avoids numbers initially and builds intuition. Data can then be introduced to support the story rather than overwhelm it.

Doctors can describe quality-adjusted life as the area under a curve without showing equations. The idea is that quality of life rises sooner and stays higher with early fitting.

A simple sketch or verbal description works. The curve for early fitting rises quickly and remains steady. The curve for late fitting stays low for longer and never fully catches up. The difference between the two curves represents lost quality-adjusted life.

This explanation is intuitive and powerful. It allows doctors to communicate complex ideas in a way that feels natural.

Quality scores can feel abstract, but daily activities are concrete. Doctors should link quality-adjusted gains to specific abilities like walking to work, using public transport, playing with children, or standing for long periods.

When doctors say early fitting adds years of being able to do these things comfortably, the data becomes real. Patients and decision-makers understand the value immediately. This anchoring makes quality-adjusted life expectancy meaningful rather than theoretical.

One common objection is that waiting allows better healing or volume stabilization. Doctors should acknowledge that healing is important but explain that early fitting does not mean unsafe fitting. It means structured, adaptive fitting with appropriate sockets and follow-up.

Early fitting can be staged and adjusted as healing progresses. This approach allows mobility without compromising safety. Presenting early fitting as a controlled process rather than a fixed event reduces fear and resistance.

Many believe that patients can simply catch up once they receive a prosthesis. Data does not support this assumption. Early inactivity leads to muscle loss, habit formation, and psychological withdrawal that are difficult to reverse.

Doctors should explain that late fitting improves function, but it rarely erases early losses completely. Quality-adjusted life expectancy captures these irreversible losses clearly. This framing helps decision-makers understand that timing has lasting consequences.

Early fitting may appear costly when viewed only through short-term budgets. Doctors should redirect the discussion toward lifetime value. The cost of years spent in low-quality states often exceeds the cost of early intervention.

By describing how early fitting reduces long-term care needs, doctors can show that visible short-term savings often lead to hidden long-term costs. This shift in perspective is essential for informed decisions.

While early fitting benefits many, some patients gain more than others. Younger patients, working adults, and those with high pre-amputation activity levels often see the largest quality-adjusted gains.

Doctors can prioritize early fitting for these groups when resources are limited. This targeted approach maximizes impact and strengthens the data supporting early intervention.

Early fitting should not depend on individual advocacy alone. Doctors can work with teams to integrate it into standard care pathways. When early fitting becomes the default rather than the exception, outcomes improve consistently.

Standardization also improves data collection. This allows doctors to build local evidence that reinforces broader findings and supports future decisions.

Doctors should periodically review long-term outcomes of early-fitted patients. This reinforces learning and strengthens confidence in the approach. Over time, patterns become clear and easier to communicate.

This reflective practice turns quality-adjusted life expectancy from a theoretical concept into lived clinical wisdom. It also builds a strong case for early fitting within institutions.

Early fitting succeeds best when devices are comfortable and adaptable. Heavy or rigid prostheses can discourage use during the early learning phase. Lightweight and modular designs support gradual adaptation.

When patients feel less burdened, they move more. Increased movement improves physical and psychological outcomes, raising quality-adjusted life expectancy. Technology choices therefore influence the success of early fitting strategies.

Early fitting requires active follow-up. Adjustments, training, and reassurance are essential. Without support, early fitting can fail and undermine confidence.

Doctors should emphasize that early fitting is a system, not just a device. Quality-adjusted gains depend on the entire care ecosystem working together. This holistic view strengthens outcomes and trust.

In India, daily life often involves uneven terrain, public transport, and long work hours. Early fitting helps patients adapt to these realities sooner. This practical adaptation improves long-term usability.

When doctors present data, they should contextualize it to Indian conditions. This makes the argument stronger and more relevant. Quality-adjusted life expectancy gains are meaningful only when grounded in lived reality.

Early prosthetic fitting should not be viewed as a short-term rehabilitation choice. It is a life-course intervention that shapes how the next decades unfold. When doctors look only at the first few months, the benefits may appear modest or gradual. When they look across an entire adult lifespan, the impact becomes clear and profound.

Quality-adjusted life expectancy captures this long view. It shows that early fitting does not merely speed up recovery. It changes the baseline from which a patient lives, works, moves, and ages. This baseline shift affects every year that follows, quietly adding up to meaningful gains in independence, confidence, and participation.

For doctors, this perspective helps align daily clinical decisions with long-term patient welfare. It explains why timing matters even when eventual fitting is guaranteed. Life does not pause while patients wait. The quality of those waiting years matters.

In India, delays in care often have deeper consequences than in settings with strong social safety nets. Many patients rely on physical work for income. Many live in environments where mobility is essential for daily survival rather than convenience. A year of inactivity in such settings has outsized effects on physical health, finances, and family stability.

Early fitting reduces these cascading losses. It allows patients to re-enter work, travel independently, and participate socially sooner. These gains protect not only the individual, but also the household. When doctors frame early fitting as a way to preserve family stability and long-term productivity, the argument becomes culturally and economically relevant.

Quality-adjusted life expectancy gains in India are therefore not abstract. They reflect real differences in how many years a person can live with dignity rather than dependence.

One of the most overlooked aspects of early fitting is its effect on dignity. Being able to stand, walk, or use a hand early changes how patients see themselves. It restores agency at a moment when loss feels overwhelming.

Over time, this sense of agency influences choices. Patients who feel capable invest more in their health, relationships, and future. These choices accumulate into better quality-adjusted life outcomes. Late fitting can restore function, but it often struggles to restore this early sense of self.

Doctors understand dignity intuitively. Quality-adjusted life expectancy gives them a way to articulate its long-term value in measurable terms.

When discussing early fitting with patients and families, doctors should emphasize that timing affects how many years are lived actively, not just how fast recovery happens. Explaining that early fitting protects future independence helps patients see beyond immediate discomfort or cost.

Doctors can also reassure families that early fitting is not rushed care. It is planned, adaptive care designed to work alongside healing. This reassurance reduces fear and builds confidence in the decision.

In institutional discussions, doctors should frame early fitting as a quality and risk management strategy. Delayed fitting increases the risk of long-term low-function states, secondary health problems, and repeated interventions. Early fitting reduces these risks and improves lifetime value per patient.

Quality-adjusted life expectancy provides a common language that bridges clinical insight and administrative priorities. It allows doctors to argue for early fitting using outcomes rather than opinion.

Doctors do not need to present complex models. Simple comparisons, life-trajectory stories, and cumulative impact explanations are often enough. Data should support the narrative, not replace it.

Using real patient scenarios and linking outcomes to daily activities makes the concept relatable. When audiences understand what the numbers represent in real life, acceptance increases.

Early fitting works best when prostheses are designed for adaptability, comfort, and rapid adjustment. Heavy, rigid, or poorly supported devices can undermine early confidence and limit benefit.

Service quality is equally important. Early fitting requires close follow-up, quick adjustments, and ongoing reassurance. Without this ecosystem, the potential quality-adjusted gains may not fully materialize.

Doctors should work with partners who understand that early fitting is a process, not a one-time event. This alignment is essential for success.

At RoboBionics, our approach to prosthetic care is built around the understanding that timing shapes lives. We design lightweight, adaptable prosthetic solutions and pair them with structured follow-up and rehabilitation support so early fitting is both safe and effective.

Our focus is not just on restoring movement, but on supporting long-term use, confidence, and independence. We see early fitting as an investment in quality-adjusted life, not just in short-term function. This belief guides how we work with doctors, hospitals, and patients across India.

Early prosthetic fitting is one of the few decisions that can quietly add years of better living to a patient’s life without adding years to their lifespan. Quality-adjusted life expectancy makes this invisible benefit visible.

For doctors, this concept strengthens advocacy. It allows clinical intuition to be backed by clear reasoning and long-term data. It helps patients and families understand why timing matters even when outcomes seem similar in the short term.

In the end, early fitting is about respect for a patient’s future. It recognizes that life after amputation is not measured only in steps taken or tasks completed, but in years lived with confidence, dignity, and choice. Quality-adjusted life expectancy gives doctors the language to defend that future clearly and responsibly.

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

For trauma amputees, the journey does not begin at the prosthetic clinic. It begins much

Amputation after cancer is not just a surgical event. It is the end of one

When a child loses a limb, the challenge is never only physical. A child’s body

Last updated: November 10, 2022

Thank you for shopping at Robo Bionics.

If, for any reason, You are not completely satisfied with a purchase We invite You to review our policy on refunds and returns.

The following terms are applicable for any products that You purchased with Us.

The words of which the initial letter is capitalized have meanings defined under the following conditions. The following definitions shall have the same meaning regardless of whether they appear in singular or in plural.

For the purposes of this Return and Refund Policy:

Company (referred to as either “the Company”, “Robo Bionics”, “We”, “Us” or “Our” in this Agreement) refers to Bionic Hope Private Limited, Pearl Haven, 1st Floor Kumbharwada, Manickpur Near St. Michael’s Church Vasai Road West, Palghar Maharashtra 401202.

Goods refer to the items offered for sale on the Website.

Orders mean a request by You to purchase Goods from Us.

Service refers to the Services Provided like Online Demo and Live Demo.

Website refers to Robo Bionics, accessible from https://robobionics.in

You means the individual accessing or using the Service, or the company, or other legal entity on behalf of which such individual is accessing or using the Service, as applicable.

You are entitled to cancel Your Service Bookings within 7 days without giving any reason for doing so, before completion of Delivery.

The deadline for cancelling a Service Booking is 7 days from the date on which You received the Confirmation of Service.

In order to exercise Your right of cancellation, You must inform Us of your decision by means of a clear statement. You can inform us of your decision by:

We will reimburse You no later than 7 days from the day on which We receive your request for cancellation, if above criteria is met. We will use the same means of payment as You used for the Service Booking, and You will not incur any fees for such reimbursement.

Please note in case you miss a Service Booking or Re-schedule the same we shall only entertain the request once.

In order for the Goods to be eligible for a return, please make sure that:

The following Goods cannot be returned:

We reserve the right to refuse returns of any merchandise that does not meet the above return conditions in our sole discretion.

Only regular priced Goods may be refunded by 50%. Unfortunately, Goods on sale cannot be refunded. This exclusion may not apply to You if it is not permitted by applicable law.

You are responsible for the cost and risk of returning the Goods to Us. You should send the Goods at the following:

We cannot be held responsible for Goods damaged or lost in return shipment. Therefore, We recommend an insured and trackable courier service. We are unable to issue a refund without actual receipt of the Goods or proof of received return delivery.

If you have any questions about our Returns and Refunds Policy, please contact us:

Last Updated on: 1st Jan 2021

These Terms and Conditions (“Terms”) govern Your access to and use of the website, platforms, applications, products and services (ively, the “Services”) offered by Robo Bionics® (a registered trademark of Bionic Hope Private Limited, also used as a trade name), a company incorporated under the Companies Act, 2013, having its Corporate office at Pearl Heaven Bungalow, 1st Floor, Manickpur, Kumbharwada, Vasai Road (West), Palghar – 401202, Maharashtra, India (“Company”, “We”, “Us” or “Our”). By accessing or using the Services, You (each a “User”) agree to be bound by these Terms and all applicable laws and regulations. If You do not agree with any part of these Terms, You must immediately discontinue use of the Services.

1.1 “Individual Consumer” means a natural person aged eighteen (18) years or above who registers to use Our products or Services following evaluation and prescription by a Rehabilitation Council of India (“RCI”)–registered Prosthetist.

1.2 “Entity Consumer” means a corporate organisation, nonprofit entity, CSR sponsor or other registered organisation that sponsors one or more Individual Consumers to use Our products or Services.

1.3 “Clinic” means an RCI-registered Prosthetics and Orthotics centre or Prosthetist that purchases products and Services from Us for fitment to Individual Consumers.

1.4 “Platform” means RehabConnect™, Our online marketplace by which Individual or Entity Consumers connect with Clinics in their chosen locations.

1.5 “Products” means Grippy® Bionic Hand, Grippy® Mech, BrawnBand™, WeightBand™, consumables, accessories and related hardware.

1.6 “Apps” means Our clinician-facing and end-user software applications supporting Product use and data collection.

1.7 “Impact Dashboard™” means the analytics interface provided to CSR, NGO, corporate and hospital sponsors.

1.8 “Services” includes all Products, Apps, the Platform and the Impact Dashboard.

2.1 Individual Consumers must be at least eighteen (18) years old and undergo evaluation and prescription by an RCI-registered Prosthetist prior to purchase or use of any Products or Services.

2.2 Entity Consumers must be duly registered under the laws of India and may sponsor one or more Individual Consumers.

2.3 Clinics must maintain valid RCI registration and comply with all applicable clinical and professional standards.

3.1 Robo Bionics acts solely as an intermediary connecting Users with Clinics via the Platform. We do not endorse or guarantee the quality, legality or outcomes of services rendered by any Clinic. Each Clinic is solely responsible for its professional services and compliance with applicable laws and regulations.

4.1 All content, trademarks, logos, designs and software on Our website, Apps and Platform are the exclusive property of Bionic Hope Private Limited or its licensors.

4.2 Subject to these Terms, We grant You a limited, non-exclusive, non-transferable, revocable license to use the Services for personal, non-commercial purposes.

4.3 You may not reproduce, modify, distribute, decompile, reverse engineer or create derivative works of any portion of the Services without Our prior written consent.

5.1 Limited Warranty. We warrant that Products will be free from workmanship defects under normal use as follows:

(a) Grippy™ Bionic Hand, BrawnBand® and WeightBand®: one (1) year from date of purchase, covering manufacturing defects only.

(b) Chargers and batteries: six (6) months from date of purchase.

(c) Grippy Mech™: three (3) months from date of purchase.

(d) Consumables (e.g., gloves, carry bags): no warranty.

5.2 Custom Sockets. Sockets fabricated by Clinics are covered only by the Clinic’s optional warranty and subject to physiological changes (e.g., stump volume, muscle sensitivity).

5.3 Exclusions. Warranty does not apply to damage caused by misuse, user negligence, unauthorised repairs, Acts of God, or failure to follow the Instruction Manual.

5.4 Claims. To claim warranty, You must register the Product online, provide proof of purchase, and follow the procedures set out in the Warranty Card.

5.5 Disclaimer. To the maximum extent permitted by law, all other warranties, express or implied, including merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, are disclaimed.

6.1 We collect personal contact details, physiological evaluation data, body measurements, sensor calibration values, device usage statistics and warranty information (“User Data”).

6.2 User Data is stored on secure servers of our third-party service providers and transmitted via encrypted APIs.

6.3 By using the Services, You consent to collection, storage, processing and transfer of User Data within Our internal ecosystem and to third-party service providers for analytics, R&D and support.

6.4 We implement reasonable security measures and comply with the Information Technology Act, 2000, and Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

6.5 A separate Privacy Policy sets out detailed information on data processing, user rights, grievance redressal and cross-border transfers, which forms part of these Terms.

7.1 Pursuant to the Information Technology Rules, 2021, We have given the Charge of Grievance Officer to our QC Head:

- Address: Grievance Officer

- Email: support@robobionics.in

- Phone: +91-8668372127

7.2 All support tickets and grievances must be submitted exclusively via the Robo Bionics Customer Support portal at https://robobionics.freshdesk.com/.

7.3 We will acknowledge receipt of your ticket within twenty-four (24) working hours and endeavour to resolve or provide a substantive response within seventy-two (72) working hours, excluding weekends and public holidays.

8.1 Pricing. Product and Service pricing is as per quotations or purchase orders agreed in writing.

8.2 Payment. We offer (a) 100% advance payment with possible incentives or (b) stage-wise payment plans without incentives.

8.3 Refunds. No refunds, except pro-rata adjustment where an Individual Consumer is medically unfit to proceed or elects to withdraw mid-stage, in which case unused stage fees apply.

9.1 Users must follow instructions provided by RCI-registered professionals and the User Manual.

9.2 Users and Entity Consumers shall indemnify and hold Us harmless from all liabilities, claims, damages and expenses arising from misuse of the Products, failure to follow professional guidance, or violation of these Terms.

10.1 To the extent permitted by law, Our total liability for any claim arising out of or in connection with these Terms or the Services shall not exceed the aggregate amount paid by You to Us in the twelve (12) months preceding the claim.

10.2 We shall not be liable for any indirect, incidental, consequential or punitive damages, including loss of profit, data or goodwill.

11.1 Our Products are classified as “Rehabilitation Aids,” not medical devices for diagnostic purposes.

11.2 Manufactured under ISO 13485:2016 quality management and tested for electrical safety under IEC 60601-1 and IEC 60601-1-2.

11.3 Products shall only be used under prescription and supervision of RCI-registered Prosthetists, Physiotherapists or Occupational Therapists.

We do not host third-party content or hardware. Any third-party services integrated with Our Apps are subject to their own terms and privacy policies.

13.1 All intellectual property rights in the Services and User Data remain with Us or our licensors.

13.2 Users grant Us a perpetual, irrevocable, royalty-free licence to use anonymised usage data for analytics, product improvement and marketing.

14.1 We may amend these Terms at any time. Material changes shall be notified to registered Users at least thirty (30) days prior to the effective date, via email and website notice.

14.2 Continued use of the Services after the effective date constitutes acceptance of the revised Terms.

Neither party shall be liable for delay or failure to perform any obligation under these Terms due to causes beyond its reasonable control, including Acts of God, pandemics, strikes, war, terrorism or government regulations.

16.1 All disputes shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

16.2 A sole arbitrator shall be appointed by Bionic Hope Private Limited or, failing agreement within thirty (30) days, by the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration.

16.3 Seat of arbitration: Mumbai, India.

16.4 Governing law: Laws of India.

16.5 Courts at Mumbai have exclusive jurisdiction over any proceedings to enforce an arbitral award.

17.1 Severability. If any provision is held invalid or unenforceable, the remainder shall remain in full force.

17.2 Waiver. No waiver of any breach shall constitute a waiver of any subsequent breach of the same or any other provision.

17.3 Assignment. You may not assign your rights or obligations without Our prior written consent.

By accessing or using the Products and/or Services of Bionic Hope Private Limited, You acknowledge that You have read, understood and agree to be bound by these Terms and Conditions.