Post-Op Follow-Up Schedule That Prevents Prosthetic Delays (For Clinicians)

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

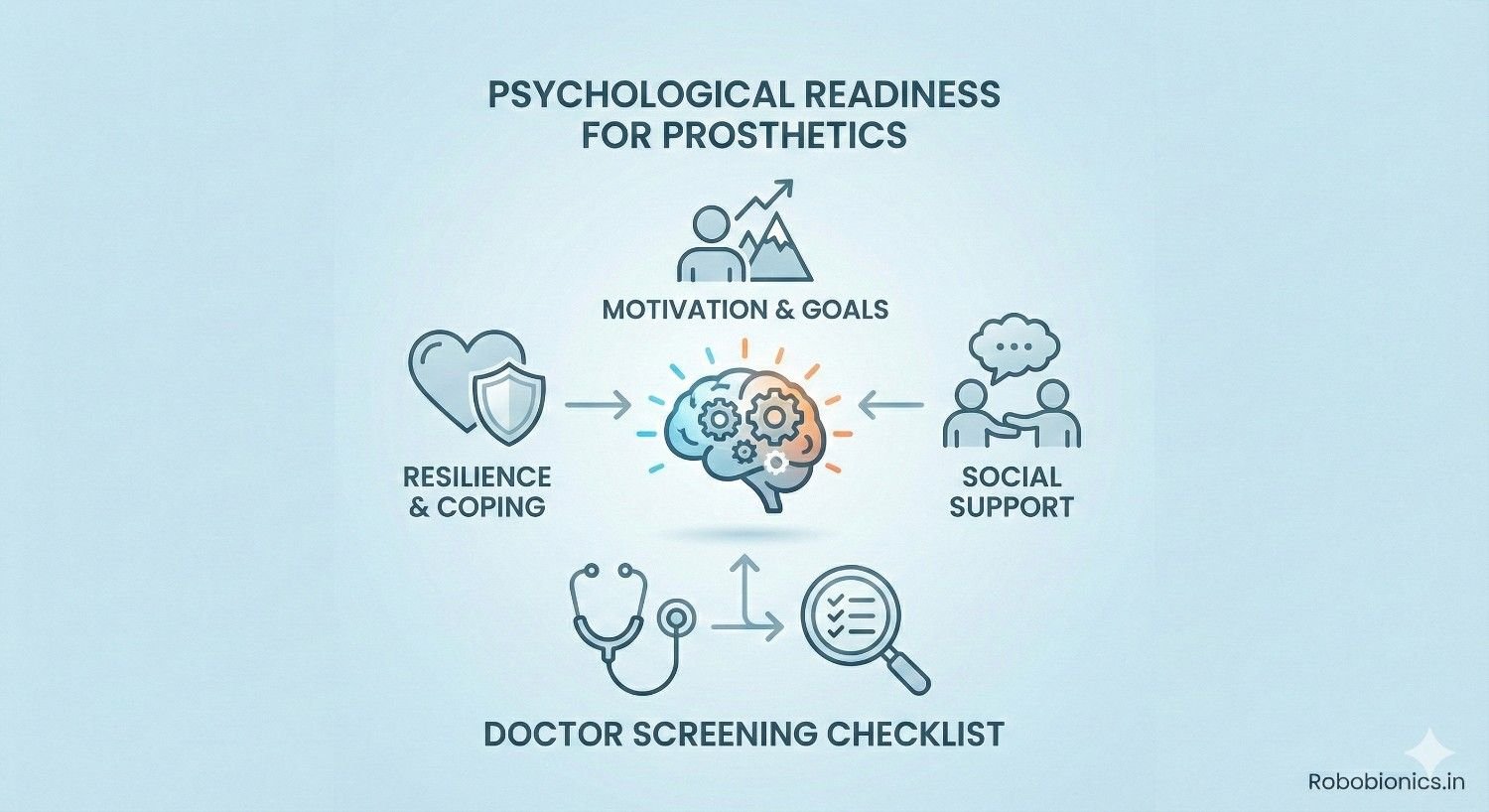

A prosthesis can restore movement, but it cannot work alone. The mind must be ready to learn, adapt, and trust the body again. When psychological readiness is ignored, even a well-fitted device may stay unused, while frustration and disappointment grow. For doctors, screening mental and emotional readiness is not extra work; it is part of safe and effective medical care.

This article explains what doctors should screen for when assessing psychological readiness for prosthetics. It focuses on clear signs, simple questions, and practical observations that fit into everyday clinical practice. The goal is to help MDs identify readiness, recognize risk early, and guide patients toward successful and lasting prosthetic use.

Before muscles learn control and skin learns tolerance, the mind decides whether the prosthesis is accepted or resisted.

Fear, doubt, or unrealistic hope can quietly block progress even when the body is medically ready.

Doctors who screen readiness early reduce the risk of abandonment later.

Motivation is the desire to improve, while readiness is the ability to engage with learning, discomfort, and change.

A patient may be highly motivated but not yet emotionally prepared for the daily effort prosthetic use requires.

Understanding this difference helps doctors plan timing more safely.

When emotional barriers are missed, patients often disengage after early setbacks.

This leads to wasted resources, lost confidence, and delayed recovery.

Early screening protects both outcomes and trust.

Limb loss triggers grief similar to other major losses, even when amputation was lifesaving.

Patients may cycle through shock, sadness, anger, or numbness.

These reactions are normal and should not be rushed.

Some patients appear calm and focused but have not emotionally processed the loss.

Denial can delay learning and surface later as frustration or withdrawal.

Doctors should gently explore feelings, not assume acceptance.

Acceptance is not a single moment but a gradual adjustment.

Patients may feel ready one week and overwhelmed the next.

Readiness should be reassessed over time.

Many patients worry that prosthetic use will cause pain or damage the limb.

This fear may limit effort or lead to avoidance.

Doctors should ask directly about pain-related fears.

Lower-limb users often fear falling, while upper-limb users fear dropping objects or appearing awkward.

These fears affect confidence and practice.

Acknowledging them early improves cooperation.

Patients with long hospital stays or repeated surgeries may associate care with fear.

This anxiety can surface during training.

Screening history helps anticipate challenges.

Some patients expect the prosthesis to work like a natural limb immediately.

When reality differs, disappointment can halt progress.

Doctors should explore what the patient expects the device to do.

Other patients underestimate their ability and avoid trying.

Low self-belief limits engagement even with good support.

Encouragement must be balanced with honesty.

Beliefs about disability, technology, or fate shape acceptance.

These beliefs influence daily use more than technical details.

Doctors should listen without judgment.

Prosthetic use involves steps, safety rules, and self-care tasks.

Patients must understand and recall guidance.

Simple screening questions reveal readiness.

Learning new movement patterns requires sustained attention.

Poor focus can increase risk and slow progress.

Doctors should note distractibility or confusion.

Prosthetic use often requires adjustment and experimentation.

Patients who can adapt tend to succeed long term.

Rigidity may signal need for extra support.

Low mood, loss of interest, or withdrawal can reduce engagement.

Depression often presents quietly in medical settings.

Doctors should screen gently but consistently.

Sadness after limb loss is expected, but persistent hopelessness is not.

Duration and impact on daily function matter.

Differentiation guides referral decisions.

Untreated depression reduces practice and tolerance.

Addressing mood improves learning and satisfaction.

Mental health care supports physical outcomes.

Patients who recognize fatigue, pain, or emotional strain adjust more safely.

Poor insight increases risk of injury or burnout.

Doctors should observe how patients describe their experiences.

Openness to feedback supports learning.

Defensiveness or withdrawal may slow progress.

This behavior offers valuable screening data.

Patients who see themselves as active partners tend to engage more.

Passive attitudes reduce long-term success.

Doctors can foster ownership through shared planning.

Supportive families motivate, while pressuring families increase stress.

Doctors should assess family dynamics.

Balance matters more than intensity.

Patients living alone may struggle emotionally during early adaptation.

Isolation increases anxiety and non-use risk.

Social context influences readiness.

Seeing others succeed with prosthetics builds confidence.

Peer exposure reduces fear of the unknown.

Doctors can encourage these connections.

Some patients face challenges directly, while others avoid discomfort.

Avoidance often delays learning.

Coping style predicts training response.

Setbacks are inevitable in prosthetic use.

Resilient patients recover faster from frustration.

Doctors should ask about past coping experiences.

Prosthetic learning takes time.

Low tolerance for slow progress may cause dropout.

Expectation setting supports patience.

Statements about learning, practice, and effort suggest engagement.

Curiosity reflects openness.

Language reveals mindset.

Expressions of hopelessness or blame suggest emotional overload.

These cues should prompt deeper discussion.

They are clinical data, not complaints.

Body posture, eye contact, and tone provide insight.

Withdrawal may signal fear or depression.

Observation complements questioning.

Brief open-ended questions often reveal more than formal scales.

Asking “What worries you most about using a prosthesis?” opens dialogue.

These questions fit routine visits.

Psychological screening does not require separate appointments.

It can be woven into standard history-taking.

Consistency matters more than length.

Some findings require mental health support before fitting.

Referral is part of good care, not delay.

Clear pathways help doctors act confidently.

Clear explanations reduce fear of the unknown.

Understanding the process builds confidence.

Education is a psychological tool.

Early success builds belief.

Small wins matter more than big promises.

Goal setting supports readiness.

Letting patients know that struggle is expected reduces shame.

This reassurance improves persistence.

Normalization supports resilience.

Even when wounds have healed and strength has returned, the mind may still be adjusting to loss, fear, or uncertainty, which can make early fitting feel overwhelming rather than empowering.

Introducing a prosthesis when emotional processing is incomplete often leads to resistance, poor engagement, or early abandonment.

Doctors should align fitting timelines with emotional readiness, not only medical clearance.

Some patients push for early fitting to escape grief, social pressure, or financial stress rather than true readiness.

This urgency may mask unresolved fear or denial.

Doctors should explore what is driving the timeline request.

Patients who ask practical questions, express curiosity, and acknowledge that learning will take time often show healthy readiness.

They accept guidance and show openness to gradual progress.

These cues suggest safer timing for fitting.

The first trial often carries heavy emotional weight, as patients imagine walking or using a hand again.

Unmanaged anticipation can turn into disappointment if reality feels unfamiliar or difficult.

Preparing patients for this gap protects morale.

Some patients freeze, withdraw, or become overly tense when first wearing a prosthesis.

These reactions signal anxiety rather than lack of ability.

Recognizing this early allows supportive pacing.

How a patient talks about the first trial afterward is highly revealing.

Hopeless language suggests distress, while reflective language suggests adaptation.

Post-session conversation is an important screening moment.

Early prosthetic training involves repetition that can feel boring or frustrating.

Patients who tolerate repetition tend to progress steadily.

Low tolerance may require shorter sessions and more encouragement.

Some discomfort is expected during learning, but panic amplifies it.

Patients who can describe discomfort calmly are safer learners.

Doctors should listen to how pain is framed, not only how intense it is.

Progress often comes in small steps rather than dramatic changes.

Patients who accept slow gains remain engaged longer.

Impatience often predicts dropout.

Looking at the prosthesis on the body can trigger strong emotional reactions.

Some patients avoid mirrors or public spaces initially.

These reactions deserve validation, not dismissal.

Limb loss can alter how patients see their role in family, work, or society.

Prosthetic use may challenge or restore identity.

Doctors should explore these shifts gently.

Comparing oneself to others with prosthetics can either motivate or discourage.

Patients with fragile self-worth may feel defeated by comparison.

Guidance helps reframe progress as personal, not competitive.

Encouraging support improves confidence, while constant monitoring or pressure increases anxiety.

Doctors should assess how family involvement feels to the patient.

Balance supports readiness.

Family members often fear falls or injury more than patients do.

This fear can limit patient confidence and independence.

Addressing caregiver anxiety is part of psychological care.

Mismatch between patient and family expectations creates stress.

Clear shared goals reduce conflict.

Doctors can facilitate this alignment.

Cultural views about disability shape how patients approach prosthetic use.

Some may see dependence as acceptable, others as failure.

These beliefs influence motivation and stress.

Concern about being seen with a prosthesis can delay use in public.

This fear often appears after discharge, not in clinic.

Doctors should prepare patients for this stage.

Pressure to return to work or social roles can both motivate and overwhelm.

Readiness depends on whether pressure aligns with capacity.

Timing should reflect balance.

Flashbacks, hypervigilance, or avoidance may appear during training.

These signs require careful pacing and possible referral.

Ignoring trauma symptoms increases dropout risk.

Repeated painful procedures can create fear of medical settings.

This fear may surface during prosthetic sessions.

Trust rebuilding is part of readiness.

Some patients appear emotionally flat rather than distressed.

This numbness can limit learning and motivation.

Gentle screening helps identify it.

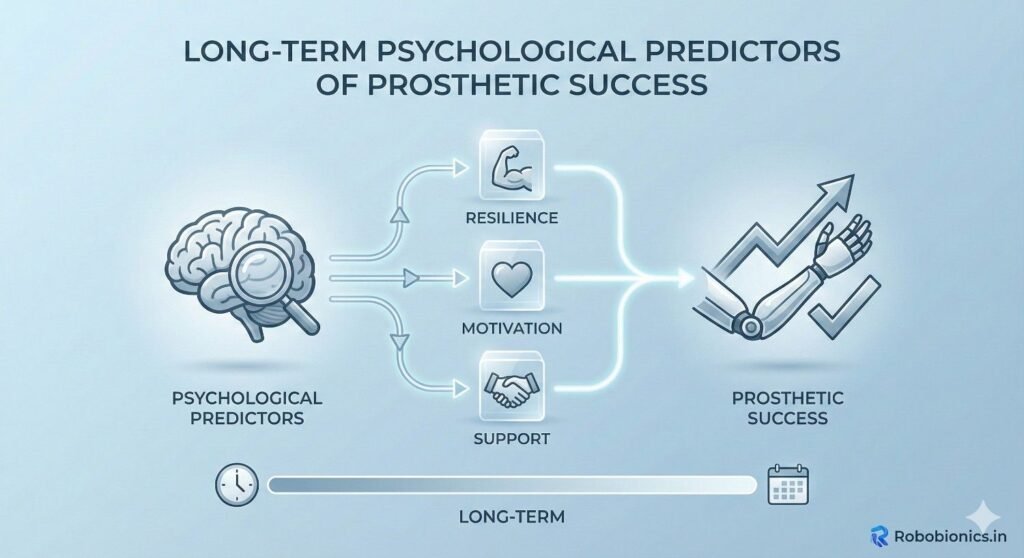

Patients driven by personal goals tend to sustain use longer.

External pressure alone rarely lasts.

Doctors should explore motivation sources.

Patients who adapt goals over time cope better with setbacks.

Rigid goals increase frustration.

Flexibility supports resilience.

Trust in doctors and therapists improves psychological safety.

Patients who feel heard engage more deeply.

The therapeutic relationship matters.

Some patients need time, counseling, or stabilization before fitting.

Clear explanation prevents feelings of rejection.

Temporary delay is protective.

Severe depression, persistent anxiety, or trauma symptoms require support.

Referral improves prosthetic outcomes.

This step is part of comprehensive care.

Hope should be preserved through education and small goals.

Patients should know readiness can change.

Support prevents disengagement.

Psychological readiness screening does not require long interviews or separate appointments, because much of the relevant information emerges naturally when doctors ask patients about daily life, worries, and expectations during routine reviews.

By listening carefully to how patients describe their situation, progress, and concerns, doctors can identify emotional readiness or risk without adding time pressure.

Consistency in asking these questions across visits matters more than depth in a single encounter.

Questions that invite reflection, such as asking patients what they find most difficult right now or what they hope life will look like after rehabilitation, often reveal beliefs, fears, and coping styles more clearly than direct psychological probes.

These conversations feel less clinical and more human, which encourages honest responses.

Doctors should allow brief pauses and avoid rushing answers, as silence often leads to meaningful insight.

Psychological readiness is best judged over time rather than in one meeting, because mood, confidence, and engagement can fluctuate during recovery.

Noting patterns such as increasing curiosity, improved participation, or reduced avoidance across visits provides strong evidence of readiness.

This longitudinal view reduces the risk of misjudging a patient based on a single good or bad day.

Brief notes about mood, engagement, expectations, and family dynamics help build a clearer picture of readiness over time.

This documentation supports continuity when care is shared across teams.

Psychological observations deserve the same respect as physical findings.

Records should describe what the patient says or does rather than label them with subjective terms.

For example, noting that a patient expresses fear of falling is more useful than writing that the patient is anxious.

Clear descriptions guide future decisions and referrals.

When mental health referral or delayed fitting is recommended, clear documentation helps patients and families understand the reasoning.

It also protects trust by showing that decisions are based on observed needs rather than opinion.

Transparency improves acceptance.

High enthusiasm at early stages can mask unresolved grief or denial, especially in patients eager to return to work or social roles.

Doctors should look beyond excitement and assess whether patients understand the effort and setbacks involved.

Balanced enthusiasm paired with realism signals healthier readiness.

Skipping emotional discussions may feel efficient, but it often leads to longer delays later due to disengagement or dropout.

Brief but regular emotional check-ins prevent bigger problems.

Addressing emotions early saves time overall.

Quiet patients may appear cooperative while internally struggling.

Silence does not always indicate agreement or readiness.

Doctors should gently invite expression rather than assume comfort.

Patients who lose a limb suddenly often struggle with shock and identity disruption even when physically strong.

Their readiness may fluctuate unpredictably as reality sets in.

Doctors should expect emotional waves rather than linear progress.

Chronic illness often leads to emotional fatigue and fear of repeated failure.

These patients may appear cautious or withdrawn rather than distressed.

Readiness assessment should consider long-term disease burden.

Children and adolescents express readiness through behavior rather than words.

Resistance, avoidance, or sudden changes in mood often signal underlying concerns.

Doctors should involve caregivers while still respecting the child’s voice.

Physiotherapists and occupational therapists often spend more time with patients and observe subtle emotional responses during training.

Their feedback adds depth to readiness assessment.

Doctors should actively seek their input.

Psychologists and counselors can help patients process grief, fear, and identity changes that block prosthetic use.

Early referral improves outcomes and does not delay rehabilitation.

Collaboration strengthens care.

Mixed messages about expectations or timelines increase anxiety and confusion.

When all team members communicate similar goals and pacing, patients feel safer.

Consistency supports trust.

Psychological adaptation does not end when the prosthesis is fitted, as new challenges often arise during real-world use.

Preparing patients for ongoing emotional adjustment prevents disappointment.

Expectation management supports resilience.

Patients who reflect on what works and what feels difficult tend to adapt better over time.

Doctors can encourage journaling or simple self-check-ins.

Self-awareness strengthens coping.

Patients should be reminded that the prosthesis is a tool, not a measure of worth.

Reinforcing identity based on roles, relationships, and values reduces emotional pressure.

This perspective supports long-term well-being.

Fitting a prosthesis before psychological readiness can cause emotional harm and loss of trust.

Doctors have an ethical duty to protect patients from this risk.

Timing decisions should prioritize well-being over speed.

Psychological screening should be presented as routine care, not a judgment.

Normalizing emotional support reduces resistance.

Respectful language matters.

Patients deserve to understand why readiness matters and how it affects outcomes.

Shared decisions improve adherence and satisfaction.

Transparency builds partnership.

Patients who are not ready today may become ready with time, education, and support.

Readiness should never be seen as a fixed trait.

This outlook preserves hope.

Major transitions such as first fitting, return home, or return to work may change emotional needs.

Doctors should reassess readiness at these points.

Regular review prevents missed signals.

Psychological readiness screening recognizes that prosthetic rehabilitation is not only physical training but also a human adaptation process.

Respecting this reality improves outcomes.

Doctors who attend to both mind and body deliver more complete care.

We have now expanded the article significantly with detailed sections on workflows, documentation, common errors, patient groups, team-based care, ethics, and long-term adaptation, while maintaining longer, connected sentences throughout.

At Robobionics, we have seen that prosthetic success is rarely limited by technology alone and is far more often shaped by whether the patient felt emotionally prepared, understood, and supported at the right time.

When doctors take psychological readiness seriously, they protect patients from early disappointment and give prosthetic care a fair chance to succeed.

Screening the mind is not separate from medical care; it is part of responsible prosthetic medicine.

Patients who feel heard, prepared, and emotionally steady approach prosthetic training with patience and openness, even when progress is slow or uncomfortable.

This mindset reduces abandonment, improves learning, and strengthens trust in the care team.

Early psychological screening often saves months of stalled rehabilitation later.

Introducing prosthetics when patients are mentally ready, rather than when timelines demand it, creates better long-term engagement and confidence.

Honest conversations about effort, setbacks, and emotional adjustment help patients form realistic expectations.

Clarity builds resilience.

Doctors, therapists, families, and prosthetic providers all influence psychological readiness through their words, pacing, and attitudes.

When the entire team respects emotional readiness, patients feel safer to try, fail, and try again.

This shared approach transforms rehabilitation into partnership.

As an Indian prosthetics manufacturer, Robobionics works closely with doctors to support not only physical fitting but also the emotional journey of prosthetic adoption.

Our approach emphasizes gradual progression, patient education, and devices designed to adapt as confidence grows.

By aligning psychological readiness with thoughtful prosthetic design and care, we aim to help doctors restore movement, dignity, and long-term confidence for every patient.

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

For trauma amputees, the journey does not begin at the prosthetic clinic. It begins much

Amputation after cancer is not just a surgical event. It is the end of one

When a child loses a limb, the challenge is never only physical. A child’s body

Last updated: November 10, 2022

Thank you for shopping at Robo Bionics.

If, for any reason, You are not completely satisfied with a purchase We invite You to review our policy on refunds and returns.

The following terms are applicable for any products that You purchased with Us.

The words of which the initial letter is capitalized have meanings defined under the following conditions. The following definitions shall have the same meaning regardless of whether they appear in singular or in plural.

For the purposes of this Return and Refund Policy:

Company (referred to as either “the Company”, “Robo Bionics”, “We”, “Us” or “Our” in this Agreement) refers to Bionic Hope Private Limited, Pearl Haven, 1st Floor Kumbharwada, Manickpur Near St. Michael’s Church Vasai Road West, Palghar Maharashtra 401202.

Goods refer to the items offered for sale on the Website.

Orders mean a request by You to purchase Goods from Us.

Service refers to the Services Provided like Online Demo and Live Demo.

Website refers to Robo Bionics, accessible from https://robobionics.in

You means the individual accessing or using the Service, or the company, or other legal entity on behalf of which such individual is accessing or using the Service, as applicable.

You are entitled to cancel Your Service Bookings within 7 days without giving any reason for doing so, before completion of Delivery.

The deadline for cancelling a Service Booking is 7 days from the date on which You received the Confirmation of Service.

In order to exercise Your right of cancellation, You must inform Us of your decision by means of a clear statement. You can inform us of your decision by:

We will reimburse You no later than 7 days from the day on which We receive your request for cancellation, if above criteria is met. We will use the same means of payment as You used for the Service Booking, and You will not incur any fees for such reimbursement.

Please note in case you miss a Service Booking or Re-schedule the same we shall only entertain the request once.

In order for the Goods to be eligible for a return, please make sure that:

The following Goods cannot be returned:

We reserve the right to refuse returns of any merchandise that does not meet the above return conditions in our sole discretion.

Only regular priced Goods may be refunded by 50%. Unfortunately, Goods on sale cannot be refunded. This exclusion may not apply to You if it is not permitted by applicable law.

You are responsible for the cost and risk of returning the Goods to Us. You should send the Goods at the following:

We cannot be held responsible for Goods damaged or lost in return shipment. Therefore, We recommend an insured and trackable courier service. We are unable to issue a refund without actual receipt of the Goods or proof of received return delivery.

If you have any questions about our Returns and Refunds Policy, please contact us:

Last Updated on: 1st Jan 2021

These Terms and Conditions (“Terms”) govern Your access to and use of the website, platforms, applications, products and services (ively, the “Services”) offered by Robo Bionics® (a registered trademark of Bionic Hope Private Limited, also used as a trade name), a company incorporated under the Companies Act, 2013, having its Corporate office at Pearl Heaven Bungalow, 1st Floor, Manickpur, Kumbharwada, Vasai Road (West), Palghar – 401202, Maharashtra, India (“Company”, “We”, “Us” or “Our”). By accessing or using the Services, You (each a “User”) agree to be bound by these Terms and all applicable laws and regulations. If You do not agree with any part of these Terms, You must immediately discontinue use of the Services.

1.1 “Individual Consumer” means a natural person aged eighteen (18) years or above who registers to use Our products or Services following evaluation and prescription by a Rehabilitation Council of India (“RCI”)–registered Prosthetist.

1.2 “Entity Consumer” means a corporate organisation, nonprofit entity, CSR sponsor or other registered organisation that sponsors one or more Individual Consumers to use Our products or Services.

1.3 “Clinic” means an RCI-registered Prosthetics and Orthotics centre or Prosthetist that purchases products and Services from Us for fitment to Individual Consumers.

1.4 “Platform” means RehabConnect™, Our online marketplace by which Individual or Entity Consumers connect with Clinics in their chosen locations.

1.5 “Products” means Grippy® Bionic Hand, Grippy® Mech, BrawnBand™, WeightBand™, consumables, accessories and related hardware.

1.6 “Apps” means Our clinician-facing and end-user software applications supporting Product use and data collection.

1.7 “Impact Dashboard™” means the analytics interface provided to CSR, NGO, corporate and hospital sponsors.

1.8 “Services” includes all Products, Apps, the Platform and the Impact Dashboard.

2.1 Individual Consumers must be at least eighteen (18) years old and undergo evaluation and prescription by an RCI-registered Prosthetist prior to purchase or use of any Products or Services.

2.2 Entity Consumers must be duly registered under the laws of India and may sponsor one or more Individual Consumers.

2.3 Clinics must maintain valid RCI registration and comply with all applicable clinical and professional standards.

3.1 Robo Bionics acts solely as an intermediary connecting Users with Clinics via the Platform. We do not endorse or guarantee the quality, legality or outcomes of services rendered by any Clinic. Each Clinic is solely responsible for its professional services and compliance with applicable laws and regulations.

4.1 All content, trademarks, logos, designs and software on Our website, Apps and Platform are the exclusive property of Bionic Hope Private Limited or its licensors.

4.2 Subject to these Terms, We grant You a limited, non-exclusive, non-transferable, revocable license to use the Services for personal, non-commercial purposes.

4.3 You may not reproduce, modify, distribute, decompile, reverse engineer or create derivative works of any portion of the Services without Our prior written consent.

5.1 Limited Warranty. We warrant that Products will be free from workmanship defects under normal use as follows:

(a) Grippy™ Bionic Hand, BrawnBand® and WeightBand®: one (1) year from date of purchase, covering manufacturing defects only.

(b) Chargers and batteries: six (6) months from date of purchase.

(c) Grippy Mech™: three (3) months from date of purchase.

(d) Consumables (e.g., gloves, carry bags): no warranty.

5.2 Custom Sockets. Sockets fabricated by Clinics are covered only by the Clinic’s optional warranty and subject to physiological changes (e.g., stump volume, muscle sensitivity).

5.3 Exclusions. Warranty does not apply to damage caused by misuse, user negligence, unauthorised repairs, Acts of God, or failure to follow the Instruction Manual.

5.4 Claims. To claim warranty, You must register the Product online, provide proof of purchase, and follow the procedures set out in the Warranty Card.

5.5 Disclaimer. To the maximum extent permitted by law, all other warranties, express or implied, including merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, are disclaimed.

6.1 We collect personal contact details, physiological evaluation data, body measurements, sensor calibration values, device usage statistics and warranty information (“User Data”).

6.2 User Data is stored on secure servers of our third-party service providers and transmitted via encrypted APIs.

6.3 By using the Services, You consent to collection, storage, processing and transfer of User Data within Our internal ecosystem and to third-party service providers for analytics, R&D and support.

6.4 We implement reasonable security measures and comply with the Information Technology Act, 2000, and Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

6.5 A separate Privacy Policy sets out detailed information on data processing, user rights, grievance redressal and cross-border transfers, which forms part of these Terms.

7.1 Pursuant to the Information Technology Rules, 2021, We have given the Charge of Grievance Officer to our QC Head:

- Address: Grievance Officer

- Email: support@robobionics.in

- Phone: +91-8668372127

7.2 All support tickets and grievances must be submitted exclusively via the Robo Bionics Customer Support portal at https://robobionics.freshdesk.com/.

7.3 We will acknowledge receipt of your ticket within twenty-four (24) working hours and endeavour to resolve or provide a substantive response within seventy-two (72) working hours, excluding weekends and public holidays.

8.1 Pricing. Product and Service pricing is as per quotations or purchase orders agreed in writing.

8.2 Payment. We offer (a) 100% advance payment with possible incentives or (b) stage-wise payment plans without incentives.

8.3 Refunds. No refunds, except pro-rata adjustment where an Individual Consumer is medically unfit to proceed or elects to withdraw mid-stage, in which case unused stage fees apply.

9.1 Users must follow instructions provided by RCI-registered professionals and the User Manual.

9.2 Users and Entity Consumers shall indemnify and hold Us harmless from all liabilities, claims, damages and expenses arising from misuse of the Products, failure to follow professional guidance, or violation of these Terms.

10.1 To the extent permitted by law, Our total liability for any claim arising out of or in connection with these Terms or the Services shall not exceed the aggregate amount paid by You to Us in the twelve (12) months preceding the claim.

10.2 We shall not be liable for any indirect, incidental, consequential or punitive damages, including loss of profit, data or goodwill.

11.1 Our Products are classified as “Rehabilitation Aids,” not medical devices for diagnostic purposes.

11.2 Manufactured under ISO 13485:2016 quality management and tested for electrical safety under IEC 60601-1 and IEC 60601-1-2.

11.3 Products shall only be used under prescription and supervision of RCI-registered Prosthetists, Physiotherapists or Occupational Therapists.

We do not host third-party content or hardware. Any third-party services integrated with Our Apps are subject to their own terms and privacy policies.

13.1 All intellectual property rights in the Services and User Data remain with Us or our licensors.

13.2 Users grant Us a perpetual, irrevocable, royalty-free licence to use anonymised usage data for analytics, product improvement and marketing.

14.1 We may amend these Terms at any time. Material changes shall be notified to registered Users at least thirty (30) days prior to the effective date, via email and website notice.

14.2 Continued use of the Services after the effective date constitutes acceptance of the revised Terms.

Neither party shall be liable for delay or failure to perform any obligation under these Terms due to causes beyond its reasonable control, including Acts of God, pandemics, strikes, war, terrorism or government regulations.

16.1 All disputes shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

16.2 A sole arbitrator shall be appointed by Bionic Hope Private Limited or, failing agreement within thirty (30) days, by the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration.

16.3 Seat of arbitration: Mumbai, India.

16.4 Governing law: Laws of India.

16.5 Courts at Mumbai have exclusive jurisdiction over any proceedings to enforce an arbitral award.

17.1 Severability. If any provision is held invalid or unenforceable, the remainder shall remain in full force.

17.2 Waiver. No waiver of any breach shall constitute a waiver of any subsequent breach of the same or any other provision.

17.3 Assignment. You may not assign your rights or obligations without Our prior written consent.

By accessing or using the Products and/or Services of Bionic Hope Private Limited, You acknowledge that You have read, understood and agree to be bound by these Terms and Conditions.