Post-Op Follow-Up Schedule That Prevents Prosthetic Delays (For Clinicians)

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

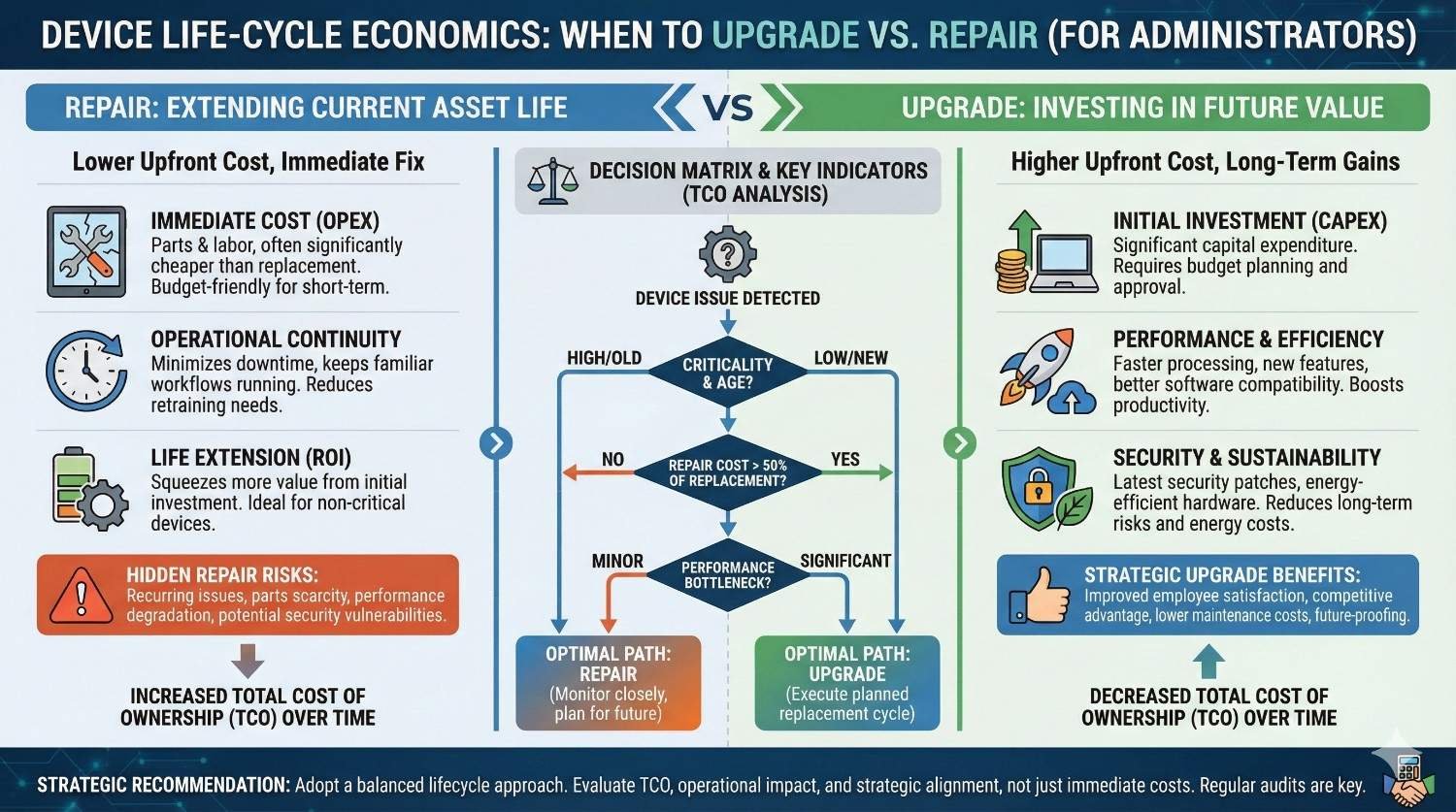

Healthcare administrators face a quiet but costly decision every day. When a prosthetic device starts showing wear, should it be repaired again or replaced with something newer? This choice often feels small in the moment, but over time it shapes budgets, outcomes, and patient trust.

This article explores device life-cycle economics in prosthetic care, with a clear focus on administrators. We will break down how devices age, where repair costs quietly add up, and when upgrading actually saves money. The aim is to offer practical thinking, not theory, using simple language and real-world logic.

Many administrators think device life cycle means how old the prosthesis is. In practice, age is only one part of the story. What matters more is how the device is used, how often it is stressed, and how well it matches the patient’s needs over time.

A two-year-old device used daily on rough terrain may be closer to end of life than a five-year-old device used lightly indoors. Life cycle decisions must look at real use, not calendar dates.

The life cycle of a prosthetic device begins at selection, not at breakdown. Choosing a device that is barely adequate at the start often shortens its useful life.

Devices that are under-specified tend to face more repairs, faster wear, and earlier replacement. This creates higher total cost even if the purchase price was lower.

Good life cycle economics start with the right match on day one.

Most prosthetic devices follow a similar pattern. The early phase is stable with minimal issues. The middle phase sees minor repairs and adjustments. The late phase shows frequent breakdowns, reduced performance, and patient dissatisfaction.

Administrators who understand these phases can plan spending instead of reacting to emergencies.

A strap replacement here. A joint tightening there. Each repair seems minor and easy to approve. Over time, these costs stack up.

What often gets missed is staff time, appointment slots, and patient travel. These indirect costs are real, even if they do not appear on a single invoice.

Repeated small repairs can cost more than a planned upgrade.

Every repair takes the device out of use, even if only for a day. For patients, this means reduced mobility. For hospitals, it means extra coordination and follow-up.

Downtime often leads to missed therapy sessions or delayed recovery. These delays increase overall care cost far beyond the repair itself.

Administrators should factor downtime into every repair decision.

Frequent repairs often signal a deeper issue. The device may no longer suit the patient’s activity level, weight, or health condition.

Continuing to repair a mismatched device is like fixing the same leak again and again without addressing the source. Costs rise while outcomes stagnate.

Recognizing mismatch early saves money.

In the early and middle phases of a device’s life, repairs often make economic sense. Components are still structurally sound, and performance remains acceptable.

At this stage, repairs extend life without major compromise. Administrators should support these repairs confidently.

The key is knowing when the device is still in a healthy phase.

Some parts are designed to wear out. Foot shells, covers, liners, and straps fall into this category.

Replacing these parts is expected and cost-effective. These repairs do not signal end of life.

Separating wear-part maintenance from structural repair helps clarify decisions.

Sometimes a repair is justified even late in life if it serves a short-term purpose. For example, keeping a device functional until a planned upgrade date.

These repairs should be approved with a clear timeline, not as open-ended solutions.

Planning turns a repair into a controlled cost.

When repairs become more frequent, cost accelerates quickly. The device spends more time in the clinic than with the patient.

Frequent visits increase administrative load and frustrate patients. Satisfaction drops, even if costs seem manageable on paper.

This is often the point where upgrade should be discussed.

As devices age, performance drops. Stability decreases. Energy cost for the patient rises.

Poor performance leads to slower walking, higher fall risk, and reduced prosthetic use. These outcomes increase downstream healthcare costs.

Upgrading restores performance and prevents secondary costs.

A clear rule many administrators use is simple. When cumulative repair cost approaches a large portion of replacement cost, replacement should be considered.

This comparison must include labor, downtime, and indirect costs. When viewed fully, replacement often wins earlier than expected.

A new device restarts the life cycle. Early-phase stability returns. Repairs drop sharply.

This reset reduces administrative effort and improves predictability. Predictability is valuable in budget planning.

Timely upgrades smooth cost instead of creating spikes.

Modern prosthetic devices often offer better durability, stability, and efficiency. These improvements reduce wear and tear.

Upgrading is not just about new features. It is about reducing future maintenance burden.

Better technology often lowers lifetime cost.

When patients walk better, they fall less and engage more in daily life. This reduces therapy needs and follow-up visits.

Improved outcomes lower long-term system cost. Administrators should view upgrades as preventive investments.

Repairs are easier to approve because they appear smaller. Replacements often need higher-level approval.

This bias leads to repair-heavy strategies that cost more over time. Administrators must look beyond immediate budget cycles.

Life cycle thinking requires longer horizons.

Repair costs are often spread across departments and time periods. Replacement cost is a single visible number.

This makes repairs feel cheaper even when they are not. Consolidated reporting helps correct this distortion.

Visibility drives better decisions.

Some administrators worry that approving upgrades sets expectations for others. This fear leads to delays.

Clear criteria for upgrade decisions prevent uncontrolled escalation. Consistency protects budgets.

Simple tracking makes decisions easier. How often has the device been repaired? How many days was it unavailable?

When these numbers cross defined thresholds, escalation should be automatic.

Objective data removes emotion from decisions.

If declining performance increases fall risk or pain, repair is no longer just a technical issue. It becomes a safety issue.

Safety-related decisions justify upgrades more strongly than comfort arguments.

Risk-based criteria are powerful.

Clinicians and prosthetists can often estimate remaining useful life. Administrators should ask for this estimate explicitly.

If remaining life is short, repairs should be limited and upgrade planning should begin.

Planning avoids emergency replacement.

Hospitals that use defined device tiers find life-cycle decisions easier. Each tier has expected life, repair patterns, and upgrade triggers.

Standardization reduces debate and speeds approval.

Consistency improves cost control.

Strong partnerships with manufacturers and service providers improve predictability. Service quality affects repair frequency and downtime.

Reliable partners reduce hidden costs.

Partnerships matter in life-cycle economics.

Administrators, clinicians, and prosthetists must share a life-cycle mindset. Training supports aligned decisions.

Aligned teams reduce friction and delay.

Shared understanding saves money.

Patients become frustrated with frequent repairs. They may miss appointments or disengage from care.

Disengagement leads to poorer outcomes and higher long-term cost.

Stable devices support engagement.

When patients see timely upgrades instead of endless repairs, trust grows. Trust improves follow-up and adherence.

Better adherence reduces complications.

Trust has economic value.

Functional devices keep patients active and independent. Independence reduces demand on healthcare services.

Upgrades that restore independence pay back over time.

Regular reviews help identify aging devices early. Reviews should look at performance, repairs, and patient satisfaction.

Early identification allows planned upgrades.

Planning reduces crisis spending.

Including expected replacements in annual budgets prevents shock. Planned spending is easier to defend than emergency requests.

Predictable budgets support smoother operations.

Preparation reduces stress.

Over time, tracking outcomes improves criteria. Data shows which devices last longer and which fail early.

Learning systems make smarter investments.

Smarter investments lower total cost.

For administrators, the purchase price of a prosthetic device is the most visible number and often the least helpful. It is easy to compare and easy to question, but it tells very little about what the device will truly cost the system over time.

A lower-priced device that needs frequent repairs, longer clinic visits, and repeated adjustments often costs more across its life than a higher-priced but stable device. Total cost of ownership looks at the full picture, not just the starting point.

Good decisions come from tracking what happens after the invoice is paid.

Total cost includes direct and indirect elements. Direct costs are repairs, replacement parts, service labor, and upgrades. Indirect costs include staff time, appointment slots, patient transport, therapy delays, and downtime.

Administrators often underestimate indirect cost because it is spread across departments. When these costs are added together, the economics of repair-heavy strategies change quickly.

Seeing the full cost changes the conversation from price to value.

Every day a device is unavailable creates ripple effects. Patients miss therapy. Recovery slows. Staff must reschedule. Sometimes temporary mobility aids are needed.

These disruptions carry real cost even if they are not billed as repairs. Devices that fail less often protect workflow and reduce hidden spending.

Reliability is a financial asset.

One effective way to justify upgrades is to compare two clear scenarios. One scenario continues with repairs over the next year or two. The other upgrades now and resets the life cycle.

When projected repair costs, downtime, and service effort are included, the upgrade scenario often shows lower total spend over the same period.

Scenario comparison makes decisions easier to defend.

Remaining useful life is a powerful concept for administrators. If a device has only limited useful life left, every repair delivers diminishing returns.

Paying for multiple repairs on a device near end of life rarely makes economic sense. Redirecting that spend toward an upgrade delivers longer-term value.

Asking teams to estimate remaining life brings structure to decisions.

One way to make upgrade costs feel more reasonable is to spread them across expected years of use. When viewed as a monthly or yearly cost, upgrades often compare favorably to repeated repairs.

This approach aligns well with budgeting and forecasting. It also reflects how cost is actually experienced over time.

Life-cycle costing reduces sticker shock.

Finance leaders often respond better to risk reduction than to performance improvement alone. Frequent repairs increase risk of falls, complaints, and adverse events.

Upgrades reduce this risk by restoring stable function. Framing upgrades as risk control rather than enhancement strengthens the case.

Stability protects both patients and budgets.

Poor device performance affects more than the prosthetic department. It influences rehab outcomes, length of stay, and readmissions.

Showing how an upgrade can reduce pressure on other departments helps leadership see system-wide benefit.

System thinking builds support.

Leadership trusts internal data more than external claims. Tracking repair frequency, downtime, and patient complaints creates a strong evidence base.

When upgrade decisions are backed by the hospital’s own numbers, approval becomes easier.

Internal proof is persuasive.

One common mistake is waiting until a device fails completely before considering replacement. At this point, the decision becomes urgent and expensive.

Emergency replacements often cost more and disrupt care. Planned upgrades avoid this premium.

Timing matters as much as choice.

Approving repairs one by one hides the cumulative picture. What feels reasonable in isolation may be costly in total.

Administrators should review repair history regularly instead of case by case.

Patterns reveal truth.

Focusing only on device condition misses an important factor. If patient function is declining, costs elsewhere are likely rising.

Life-cycle decisions should include functional outcomes, not just mechanical status.

Function drives value.

Clear thresholds help teams know when to escalate. For example, a defined number of repairs within a period, or a set amount of downtime.

When thresholds are reached, upgrade review becomes automatic rather than subjective.

Rules reduce conflict.

Life-cycle decisions work best when prosthetists, rehab teams, and administrators share responsibility.

Each group sees different costs and risks. Bringing them together creates balanced decisions.

Shared ownership improves outcomes.

Recording why a repair or upgrade was chosen builds institutional memory. Over time, this documentation improves consistency.

Learning from past decisions strengthens future ones.

Consistency saves money.

Sometimes upgrades make sense not because the old device is failing, but because new technology significantly improves durability or safety.

In such cases, sticking with older devices may increase long-term cost despite acceptable current performance.

Administrators should stay informed about meaningful technology shifts.

Not every new feature justifies an upgrade. Administrators should focus on changes that reduce repairs, downtime, or risk.

Clear criteria help avoid unnecessary spending.

Value matters more than novelty.

Some patients benefit more from upgrades than others. High-activity users or high-risk patients often justify earlier upgrades.

Targeted upgrades improve ROI.

Matching investment to need is key.

When life cycles are managed actively, replacements become expected events, not surprises.

Predictable spend is easier to plan and defend. It reduces emergency approvals and budget stress.

Predictability is a strategic advantage.

Using device age, usage patterns, and repair history, administrators can forecast replacements over coming years.

These forecasts support smoother capital planning.

Planning reduces disruption.

Strong data on usage and replacement timing strengthens vendor negotiations. Volume planning and long-term partnerships can reduce cost.

Data improves leverage.

Leverage improves value.

Patients with stable devices attend therapy, follow care plans, and stay active. Engagement reduces complications.

Stable engagement lowers cost.

Repeated breakdowns erode patient trust. Distrust leads to disengagement and complaints.

Managing life cycles well protects trust.

Trust protects outcomes.

Functional devices support independence. Independence reduces demand on healthcare services.

Upgrades that restore function often pay back over time.

Track repair frequency, downtime, and performance. Visibility is the foundation of good decisions.

What gets tracked gets managed.

Create simple criteria for when repairs continue and when upgrades are reviewed.

Rules reduce debate and delay.

Budget for expected replacements. Review devices before failure. Align teams around life-cycle goals.

Planned action costs less than emergency response.

Device life-cycle economics is not about choosing between repair and upgrade in isolation. It is about managing cost, risk, and outcomes over time.

Administrators who adopt life-cycle thinking move from reactive spending to strategic investment. They reduce hidden costs, improve patient experience, and protect system stability.

In prosthetic care, the right time to upgrade is often earlier than it feels, and later than it looks on paper. The difference lies in understanding the full life cycle.

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

For trauma amputees, the journey does not begin at the prosthetic clinic. It begins much

Amputation after cancer is not just a surgical event. It is the end of one

When a child loses a limb, the challenge is never only physical. A child’s body

Last updated: November 10, 2022

Thank you for shopping at Robo Bionics.

If, for any reason, You are not completely satisfied with a purchase We invite You to review our policy on refunds and returns.

The following terms are applicable for any products that You purchased with Us.

The words of which the initial letter is capitalized have meanings defined under the following conditions. The following definitions shall have the same meaning regardless of whether they appear in singular or in plural.

For the purposes of this Return and Refund Policy:

Company (referred to as either “the Company”, “Robo Bionics”, “We”, “Us” or “Our” in this Agreement) refers to Bionic Hope Private Limited, Pearl Haven, 1st Floor Kumbharwada, Manickpur Near St. Michael’s Church Vasai Road West, Palghar Maharashtra 401202.

Goods refer to the items offered for sale on the Website.

Orders mean a request by You to purchase Goods from Us.

Service refers to the Services Provided like Online Demo and Live Demo.

Website refers to Robo Bionics, accessible from https://robobionics.in

You means the individual accessing or using the Service, or the company, or other legal entity on behalf of which such individual is accessing or using the Service, as applicable.

You are entitled to cancel Your Service Bookings within 7 days without giving any reason for doing so, before completion of Delivery.

The deadline for cancelling a Service Booking is 7 days from the date on which You received the Confirmation of Service.

In order to exercise Your right of cancellation, You must inform Us of your decision by means of a clear statement. You can inform us of your decision by:

We will reimburse You no later than 7 days from the day on which We receive your request for cancellation, if above criteria is met. We will use the same means of payment as You used for the Service Booking, and You will not incur any fees for such reimbursement.

Please note in case you miss a Service Booking or Re-schedule the same we shall only entertain the request once.

In order for the Goods to be eligible for a return, please make sure that:

The following Goods cannot be returned:

We reserve the right to refuse returns of any merchandise that does not meet the above return conditions in our sole discretion.

Only regular priced Goods may be refunded by 50%. Unfortunately, Goods on sale cannot be refunded. This exclusion may not apply to You if it is not permitted by applicable law.

You are responsible for the cost and risk of returning the Goods to Us. You should send the Goods at the following:

We cannot be held responsible for Goods damaged or lost in return shipment. Therefore, We recommend an insured and trackable courier service. We are unable to issue a refund without actual receipt of the Goods or proof of received return delivery.

If you have any questions about our Returns and Refunds Policy, please contact us:

Last Updated on: 1st Jan 2021

These Terms and Conditions (“Terms”) govern Your access to and use of the website, platforms, applications, products and services (ively, the “Services”) offered by Robo Bionics® (a registered trademark of Bionic Hope Private Limited, also used as a trade name), a company incorporated under the Companies Act, 2013, having its Corporate office at Pearl Heaven Bungalow, 1st Floor, Manickpur, Kumbharwada, Vasai Road (West), Palghar – 401202, Maharashtra, India (“Company”, “We”, “Us” or “Our”). By accessing or using the Services, You (each a “User”) agree to be bound by these Terms and all applicable laws and regulations. If You do not agree with any part of these Terms, You must immediately discontinue use of the Services.

1.1 “Individual Consumer” means a natural person aged eighteen (18) years or above who registers to use Our products or Services following evaluation and prescription by a Rehabilitation Council of India (“RCI”)–registered Prosthetist.

1.2 “Entity Consumer” means a corporate organisation, nonprofit entity, CSR sponsor or other registered organisation that sponsors one or more Individual Consumers to use Our products or Services.

1.3 “Clinic” means an RCI-registered Prosthetics and Orthotics centre or Prosthetist that purchases products and Services from Us for fitment to Individual Consumers.

1.4 “Platform” means RehabConnect™, Our online marketplace by which Individual or Entity Consumers connect with Clinics in their chosen locations.

1.5 “Products” means Grippy® Bionic Hand, Grippy® Mech, BrawnBand™, WeightBand™, consumables, accessories and related hardware.

1.6 “Apps” means Our clinician-facing and end-user software applications supporting Product use and data collection.

1.7 “Impact Dashboard™” means the analytics interface provided to CSR, NGO, corporate and hospital sponsors.

1.8 “Services” includes all Products, Apps, the Platform and the Impact Dashboard.

2.1 Individual Consumers must be at least eighteen (18) years old and undergo evaluation and prescription by an RCI-registered Prosthetist prior to purchase or use of any Products or Services.

2.2 Entity Consumers must be duly registered under the laws of India and may sponsor one or more Individual Consumers.

2.3 Clinics must maintain valid RCI registration and comply with all applicable clinical and professional standards.

3.1 Robo Bionics acts solely as an intermediary connecting Users with Clinics via the Platform. We do not endorse or guarantee the quality, legality or outcomes of services rendered by any Clinic. Each Clinic is solely responsible for its professional services and compliance with applicable laws and regulations.

4.1 All content, trademarks, logos, designs and software on Our website, Apps and Platform are the exclusive property of Bionic Hope Private Limited or its licensors.

4.2 Subject to these Terms, We grant You a limited, non-exclusive, non-transferable, revocable license to use the Services for personal, non-commercial purposes.

4.3 You may not reproduce, modify, distribute, decompile, reverse engineer or create derivative works of any portion of the Services without Our prior written consent.

5.1 Limited Warranty. We warrant that Products will be free from workmanship defects under normal use as follows:

(a) Grippy™ Bionic Hand, BrawnBand® and WeightBand®: one (1) year from date of purchase, covering manufacturing defects only.

(b) Chargers and batteries: six (6) months from date of purchase.

(c) Grippy Mech™: three (3) months from date of purchase.

(d) Consumables (e.g., gloves, carry bags): no warranty.

5.2 Custom Sockets. Sockets fabricated by Clinics are covered only by the Clinic’s optional warranty and subject to physiological changes (e.g., stump volume, muscle sensitivity).

5.3 Exclusions. Warranty does not apply to damage caused by misuse, user negligence, unauthorised repairs, Acts of God, or failure to follow the Instruction Manual.

5.4 Claims. To claim warranty, You must register the Product online, provide proof of purchase, and follow the procedures set out in the Warranty Card.

5.5 Disclaimer. To the maximum extent permitted by law, all other warranties, express or implied, including merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, are disclaimed.

6.1 We collect personal contact details, physiological evaluation data, body measurements, sensor calibration values, device usage statistics and warranty information (“User Data”).

6.2 User Data is stored on secure servers of our third-party service providers and transmitted via encrypted APIs.

6.3 By using the Services, You consent to collection, storage, processing and transfer of User Data within Our internal ecosystem and to third-party service providers for analytics, R&D and support.

6.4 We implement reasonable security measures and comply with the Information Technology Act, 2000, and Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

6.5 A separate Privacy Policy sets out detailed information on data processing, user rights, grievance redressal and cross-border transfers, which forms part of these Terms.

7.1 Pursuant to the Information Technology Rules, 2021, We have given the Charge of Grievance Officer to our QC Head:

- Address: Grievance Officer

- Email: support@robobionics.in

- Phone: +91-8668372127

7.2 All support tickets and grievances must be submitted exclusively via the Robo Bionics Customer Support portal at https://robobionics.freshdesk.com/.

7.3 We will acknowledge receipt of your ticket within twenty-four (24) working hours and endeavour to resolve or provide a substantive response within seventy-two (72) working hours, excluding weekends and public holidays.

8.1 Pricing. Product and Service pricing is as per quotations or purchase orders agreed in writing.

8.2 Payment. We offer (a) 100% advance payment with possible incentives or (b) stage-wise payment plans without incentives.

8.3 Refunds. No refunds, except pro-rata adjustment where an Individual Consumer is medically unfit to proceed or elects to withdraw mid-stage, in which case unused stage fees apply.

9.1 Users must follow instructions provided by RCI-registered professionals and the User Manual.

9.2 Users and Entity Consumers shall indemnify and hold Us harmless from all liabilities, claims, damages and expenses arising from misuse of the Products, failure to follow professional guidance, or violation of these Terms.

10.1 To the extent permitted by law, Our total liability for any claim arising out of or in connection with these Terms or the Services shall not exceed the aggregate amount paid by You to Us in the twelve (12) months preceding the claim.

10.2 We shall not be liable for any indirect, incidental, consequential or punitive damages, including loss of profit, data or goodwill.

11.1 Our Products are classified as “Rehabilitation Aids,” not medical devices for diagnostic purposes.

11.2 Manufactured under ISO 13485:2016 quality management and tested for electrical safety under IEC 60601-1 and IEC 60601-1-2.

11.3 Products shall only be used under prescription and supervision of RCI-registered Prosthetists, Physiotherapists or Occupational Therapists.

We do not host third-party content or hardware. Any third-party services integrated with Our Apps are subject to their own terms and privacy policies.

13.1 All intellectual property rights in the Services and User Data remain with Us or our licensors.

13.2 Users grant Us a perpetual, irrevocable, royalty-free licence to use anonymised usage data for analytics, product improvement and marketing.

14.1 We may amend these Terms at any time. Material changes shall be notified to registered Users at least thirty (30) days prior to the effective date, via email and website notice.

14.2 Continued use of the Services after the effective date constitutes acceptance of the revised Terms.

Neither party shall be liable for delay or failure to perform any obligation under these Terms due to causes beyond its reasonable control, including Acts of God, pandemics, strikes, war, terrorism or government regulations.

16.1 All disputes shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

16.2 A sole arbitrator shall be appointed by Bionic Hope Private Limited or, failing agreement within thirty (30) days, by the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration.

16.3 Seat of arbitration: Mumbai, India.

16.4 Governing law: Laws of India.

16.5 Courts at Mumbai have exclusive jurisdiction over any proceedings to enforce an arbitral award.

17.1 Severability. If any provision is held invalid or unenforceable, the remainder shall remain in full force.

17.2 Waiver. No waiver of any breach shall constitute a waiver of any subsequent breach of the same or any other provision.

17.3 Assignment. You may not assign your rights or obligations without Our prior written consent.

By accessing or using the Products and/or Services of Bionic Hope Private Limited, You acknowledge that You have read, understood and agree to be bound by these Terms and Conditions.