Post-Op Follow-Up Schedule That Prevents Prosthetic Delays (For Clinicians)

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

Age changes the body in ways that are slow, layered, and deeply personal. When an older adult faces limb loss, the decision to use a prosthetic is never just about replacing what is missing. It is about strength, balance, confidence, safety, and the ability to live daily life with dignity. For geriatric patients, prosthetics must support life as it is, not life as it once was.

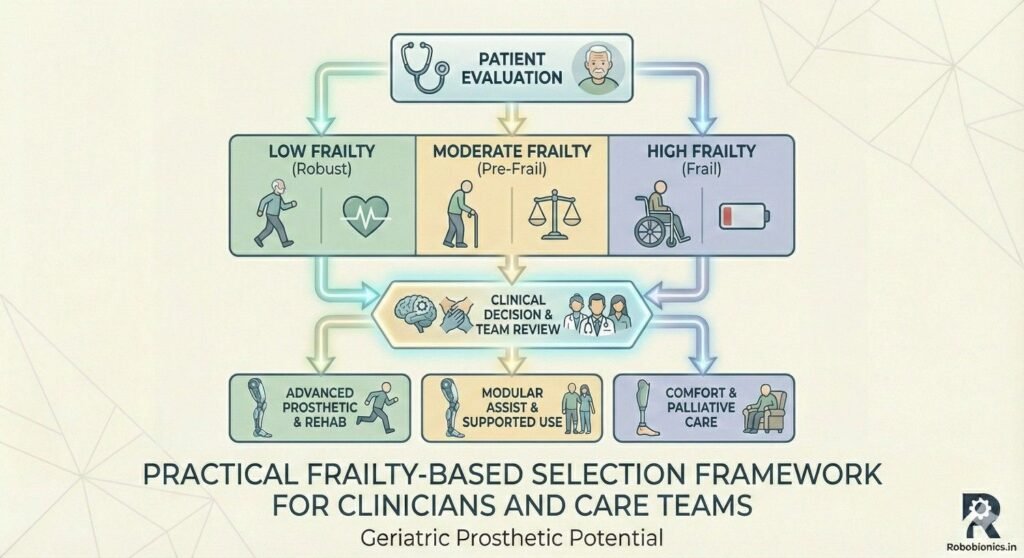

At Robobionics, we work closely with elderly patients across India and beyond. Over the years, one truth has become very clear. Chronological age alone should never decide whether a person is suitable for a prosthetic. What matters far more is frailty. Frailty reflects how the body handles stress, how quickly it recovers, and how safely it can adapt to new movement demands. Two people of the same age can have very different outcomes with the same device.

This article focuses on frailty-based selection criteria for prosthetics in geriatric patients. It explains how strength, endurance, balance, cognition, and daily habits shape prosthetic success. It also highlights how the right device choice can reduce fall risk, improve independence, and protect long-term health. The goal is not to push technology, but to match it carefully to the person using it.

If you are a caregiver, clinician, or an older adult exploring prosthetic options, this guide will help you make informed, realistic, and safe decisions. Prosthetics for the elderly are not about doing more. They are about doing what matters, with confidence and comfort.

Frailty is not the same as weakness, and it is not the same as age.

It is a combination of reduced strength, slower movement, and lower reserve.

A frail body struggles to bounce back after stress, illness, or change.

For prosthetic use, this matters more than almost any medical label.

A device adds physical and mental load to the body.

Frailty tells us how well that load can be handled safely.

Frailty also changes over time.

A patient may be stable today and vulnerable six months later.

This makes careful, ongoing assessment very important.

Age only tells us how long someone has lived.

It does not tell us how they move, think, or recover.

Two people aged seventy-five can have opposite outcomes with prosthetics.

One may walk daily, climb stairs, and manage self-care alone.

Another may tire quickly, fear falls, and depend on support.

Treating them the same would be unsafe and unfair.

Frailty-based selection respects these differences.

It allows clinicians to match function, not just technology.

This approach reduces failure, injury, and frustration.

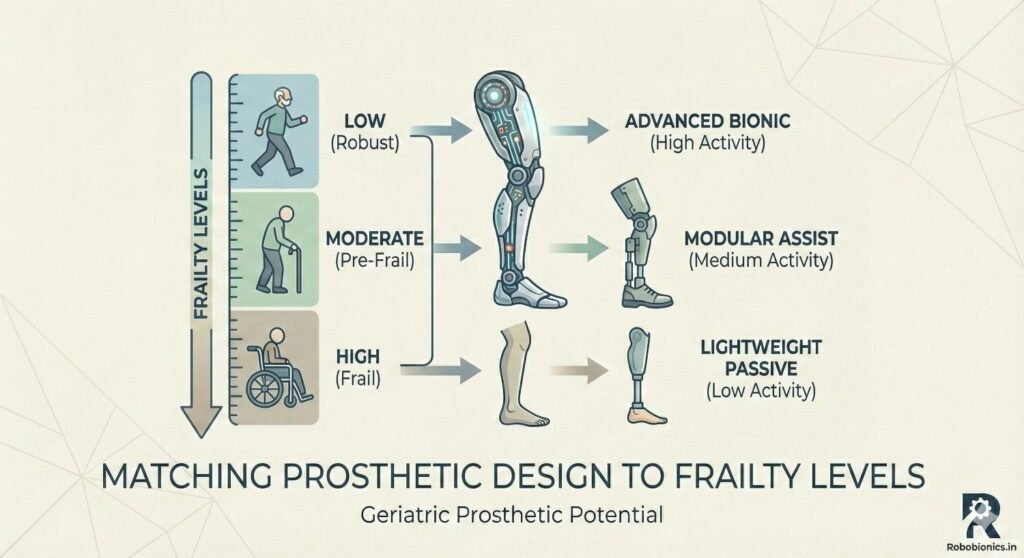

Frailty is not a switch that is either on or off.

It exists on a wide spectrum, from mild to severe.

Most elderly patients fall somewhere in the middle.

Mild frailty may allow active prosthetic use with support.

Moderate frailty may need simpler designs and limited goals.

Severe frailty may shift focus to comfort and safety instead.

Understanding where a patient lies on this spectrum guides every decision.

It shapes design choice, training plans, and long-term expectations.

This is the foundation of responsible geriatric prosthetic care.

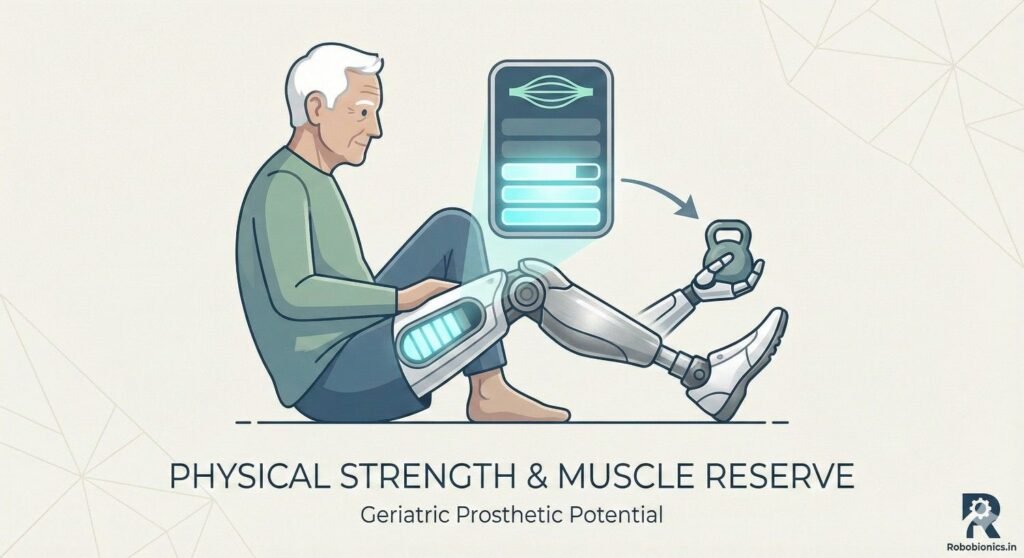

Prosthetic limbs place extra demand on muscles and joints.

For older adults, this demand can be significant.

Weak muscles increase fatigue and raise fall risk.

Strength in the hips, thighs, and core is especially important.

These muscles control balance and forward movement.

Without them, even the best prosthetic will feel unstable.

Assessment should focus on functional strength.

Simple actions like standing from a chair reveal a lot.

This gives clearer insight than isolated muscle tests.

Many geriatric patients rely on walkers or canes.

Using these requires arm and shoulder strength.

This is often overlooked during prosthetic planning.

Weak arms limit safe prosthetic use.

They reduce the ability to recover from imbalance.

They also increase fear during walking.

Evaluating grip, shoulder range, and endurance is essential.

These factors influence device choice and training pace.

Ignoring them can lead to early abandonment.

Strength alone is not enough.

Endurance determines how long a prosthetic can be used.

Elderly patients often fatigue quickly.

Short bursts of activity may be possible.

Sustained walking may not be realistic.

This affects daily prosthetic goals.

Understanding fatigue patterns helps set safe limits.

It prevents overuse injuries and discouragement.

Realistic planning builds long-term trust and success.

Balance declines naturally with age.

Vision, sensation, and reflexes all slow down.

Limb loss further challenges this system.

A prosthetic changes how weight is distributed.

The brain must relearn balance responses.

This takes time and energy.

For frail patients, this adaptation is harder.

They have less reserve to correct mistakes.

This makes fall prevention a top priority.

Past falls predict future falls very strongly.

This is especially true in older adults.

A fall history must never be ignored.

Frequent falls suggest balance or strength issues.

They may also reflect fear and hesitation.

Both affect prosthetic safety.

Understanding why falls happened matters.

Was it weakness, dizziness, or poor vision?

Each cause requires a different prosthetic strategy.

Home environments affect balance daily.

Uneven floors, stairs, and poor lighting increase risk.

Many elderly homes are not prosthetic-friendly.

A device that works in a clinic may fail at home.

Real-world conditions must guide selection.

Sometimes simplicity is safer than advanced features.

Home assessments and caregiver input are very valuable.

They help align the prosthetic with daily reality.

This reduces accidents and builds confidence.

Using a prosthetic is not automatic.

It requires attention, planning, and adjustment.

The brain works constantly during movement.

For older adults, this cognitive load can be tiring.

Frailty often includes slower processing speed.

This affects learning new motor skills.

Devices should match cognitive capacity.

Complex systems may overwhelm some patients.

Simplicity often improves long-term success.

Training involves repeated instructions.

Patients must remember safe movement patterns.

Memory issues can interfere with this process.

Forgetting steps increases fall risk.

It can also damage the device.

This creates stress for patients and caregivers.

Assessing short-term memory is important.

Clear cues and repetition help learning.

Design choices should support easy recall.

Safe prosthetic use requires good judgment.

Patients must know when to rest or stop.

They must recognize unsafe situations.

Impaired judgment raises injury risk.

This is common in advanced frailty.

Ignoring it can have serious consequences.

Caregiver involvement becomes essential here.

Shared decision-making improves safety.

Prosthetics should support, not challenge, awareness limits.

Vision guides foot placement and balance.

Poor eyesight increases missteps and trips.

This is common in older adults.

Depth perception is especially important.

It affects stair use and uneven surfaces.

Prosthetic users rely heavily on visual cues.

Vision checks should be part of assessment.

Device choice may need visual compensation strategies.

Ignoring vision issues increases fall risk significantly.

Aging reduces sensation in feet and joints.

Conditions like diabetes worsen this.

Prosthetic users already lack natural limb feedback.

Reduced sensation makes balance harder.

It delays response to uneven ground.

This increases instability.

Socket design and fit become critical here.

Comfortable contact improves body awareness.

Small adjustments can make large safety differences.

Hearing supports balance indirectly.

It helps detect environmental threats.

Poor hearing can increase surprise and missteps.

In busy environments, this matters a lot.

Traffic, crowds, and home noises guide movement.

Hearing loss adds another layer of risk.

While prosthetics cannot fix hearing, planning can adapt.

Slower walking goals may be safer.

Environment control becomes more important.

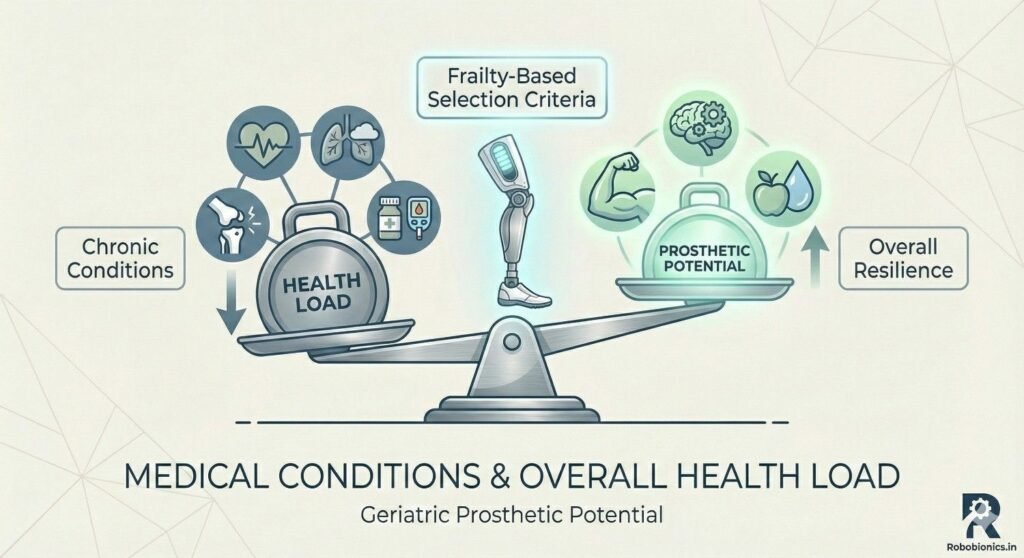

Many geriatric patients live with multiple conditions.

Heart disease, lung issues, and arthritis are common.

These affect energy and endurance.

Prosthetic walking increases energy use.

For frail bodies, this can be exhausting.

Overexertion may worsen health.

Medical stability must come first.

Prosthetic goals should respect energy limits.

Health protection is always the priority.

Joint pain alters movement patterns.

It reduces confidence and increases stiffness.

Prosthetic use can stress other joints.

Knees, hips, and spine are especially vulnerable.

Poor alignment increases pain over time.

This leads to reduced use or abandonment.

Careful alignment and shock absorption help.

Sometimes lower activity goals are wiser.

Comfort supports long-term acceptance.

Many medications affect alertness and balance.

Sedatives, blood pressure drugs, and painkillers are common.

Side effects may fluctuate daily.

Dizziness or drowsiness increases fall risk.

This interacts dangerously with prosthetic use.

Timing and monitoring are essential.

Clinicians should review medication profiles.

Caregivers should watch for changes.

Prosthetic plans must adapt to real-life effects.

Fear is powerful in older adults.

A single fall can change behavior permanently.

This fear affects prosthetic success.

Hesitation leads to stiff, unsafe movement.

It increases fall risk instead of reducing it.

Confidence must be rebuilt slowly.

Device choice should support emotional comfort.

Stable, predictable designs reduce anxiety.

Trust grows with consistent positive experiences.

Motivation varies widely in geriatric patients.

Some want independence at all costs.

Others prioritize comfort and rest.

Understanding personal goals is essential.

Prosthetics should serve life priorities.

They should never be forced.

When goals align with capacity, outcomes improve.

When they do not, frustration follows.

Honest conversations prevent disappointment.

Depression is common after limb loss.

It affects energy, focus, and engagement.

Frailty can worsen emotional vulnerability.

Low mood reduces training participation.

It slows learning and increases withdrawal.

This impacts prosthetic success directly.

Psychological support should not be optional.

Small emotional improvements have large functional effects.

Holistic care improves outcomes significantly.

Caregivers often play a central role.

They assist with donning, balance, and safety.

Their involvement shapes success.

A prosthetic that requires complex handling may fail.

Caregiver capacity must be considered.

Simple systems reduce daily stress.

Training caregivers is as important as training patients.

Shared understanding improves safety.

It also builds confidence on both sides.

Living alone changes prosthetic planning.

Safety margins must be higher.

Emergency recovery options are limited.

Assisted living offers more support.

This may allow slightly higher function goals.

Environment control improves safety.

Understanding daily routines is essential.

Prosthetics must fit real life, not ideals.

Context determines practicality.

Prosthetics need ongoing adjustment.

Fit changes with health and weight.

Older adults may struggle with travel.

Limited follow-up increases discomfort and risk.

This leads to reduced use.

Local support access is very important.

Designs should allow easy servicing.

Durability and reliability matter greatly.

Consistency builds long-term trust.

Highly frail patients benefit from simplicity.

Fewer moving parts reduce learning demands.

Predictable behavior improves safety.

These designs prioritize stability over speed.

They support short, safe movements.

This aligns with realistic daily needs.

Advanced technology is not always better.

Appropriate technology is better.

Safety always comes first.

Some patients fall in the middle range.

They have limitations but also potential.

Careful balance is needed.

These users may benefit from controlled features.

Energy-saving elements can help.

Training must be paced carefully.

Progress should be gradual and monitored.

Overambition increases risk.

Steady improvement builds confidence.

Overprescription overwhelms frail patients.

Underprescription limits capable ones.

Both cause dissatisfaction.

Frailty-based matching avoids these errors.

It respects current ability and future change.

This leads to better long-term use.

Reassessment should be ongoing.

Needs evolve with health changes.

Flexibility is a key principle.

Geriatric training must be patient-centered.

Sessions should be shorter and frequent.

Rest is part of progress.

Repetition builds motor memory.

Consistency reduces cognitive load.

Rushing increases fear and error.

Training should mirror daily tasks.

Clinic success must translate to home.

Realism improves retention.

Progress is not always linear.

Plateaus and setbacks are normal.

Monitoring helps adjust expectations.

Red flags include increasing falls or pain.

Fatigue beyond recovery is another sign.

These require immediate attention.

Open communication encourages early reporting.

This prevents serious complications.

Safety depends on vigilance.

Frailty can change over time.

Health events may reduce capacity.

Prosthetic plans must adapt.

Periodic reassessment is essential.

Device changes may be needed.

Goals may shift toward comfort.

A successful prosthetic journey is dynamic.

It evolves with the person.

This mindset ensures sustainable outcomes.

In geriatric prosthetic care, ethical decision-making begins with honesty. Older patients and their families often come with hope, sometimes shaped by stories of advanced technology or younger users achieving high mobility. While hope is important, it must be balanced with a clear understanding of what the body can realistically handle. Overpromising outcomes can lead to physical harm, emotional distress, and loss of trust. Ethical care means setting goals that are achievable, safe, and meaningful for the patient’s current stage of life.

Frailty-based selection helps ground these conversations. It shifts the focus from what a device can do to what a person can safely do with it. This approach respects the patient’s dignity by avoiding unnecessary struggle or repeated failure. Ethical practice does not mean limiting ambition without reason, but it does mean protecting patients from expectations that place them at risk. When outcomes align with reality, satisfaction and long-term use improve significantly.

Informed consent in geriatric prosthetics goes beyond signing forms. It requires ensuring that the patient truly understands the physical effort, learning process, risks, and daily commitment involved. Frail patients may nod in agreement without fully grasping the implications, especially when overwhelmed by medical settings or family pressure. Ethical responsibility lies in slowing down these discussions and confirming understanding through simple, repeated explanations.

Family members often play a key role in decision-making, but the patient’s voice must remain central. Even when cognitive decline is present, patients should be included to the fullest extent possible. Respecting autonomy builds cooperation and trust during rehabilitation. When everyone involved shares the same understanding of goals and limits, the prosthetic journey becomes safer and more supportive.

Modern prosthetics offer impressive features, but technology should never drive prescription decisions for frail elderly patients. Ethical care requires resisting the urge to showcase advanced devices when simpler solutions would serve the patient better. Complex systems can increase cognitive load, maintenance demands, and fall risk. They may also create emotional pressure to perform beyond safe limits.

Frailty-based selection acts as a safeguard against technology bias. It ensures that devices are chosen for function, comfort, and safety rather than novelty. Ethical practice prioritizes long-term well-being over short-term excitement. This approach leads to better adherence, fewer complications, and a more positive overall experience for geriatric users.

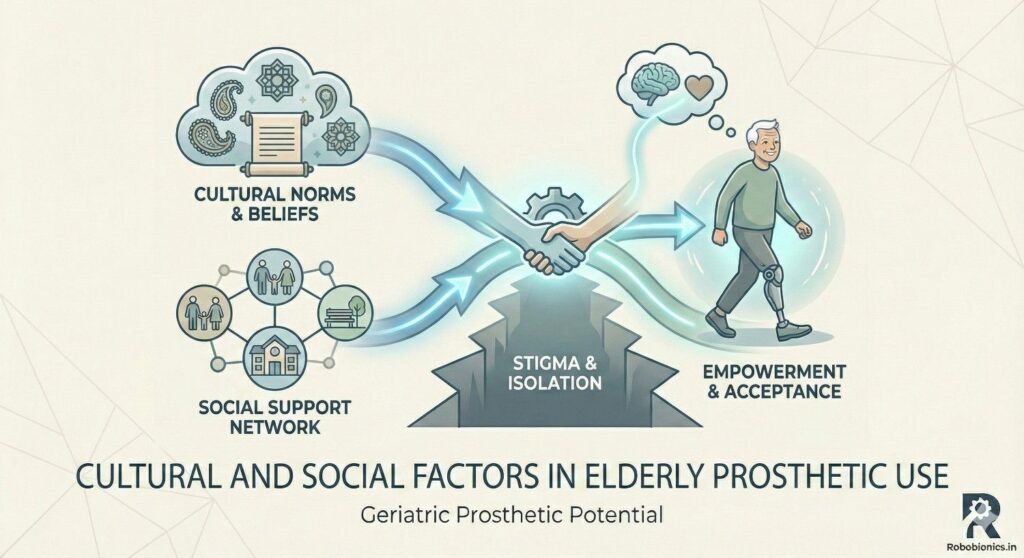

In many parts of India, healthcare decisions for elderly patients are deeply family-centered. Children and caregivers often take responsibility for treatment choices, finances, and daily care. While this support can be beneficial, it can also influence prosthetic decisions in ways that do not always align with the patient’s frailty level or personal wishes. Understanding these dynamics is essential for ethical and practical prosthetic planning.

Clinicians must navigate family expectations with sensitivity. Clear communication about frailty, safety, and realistic outcomes helps align family goals with patient needs. When families understand that a simpler prosthetic can offer greater safety and independence, resistance often decreases. Respecting cultural values while advocating for patient-centered care is a delicate but necessary balance.

Social attitudes toward disability and aging influence prosthetic acceptance among elderly patients. Some may feel that using a prosthetic at an advanced age is unnecessary or burdensome. Others may fear being judged or pitied. These perceptions can affect motivation, confidence, and willingness to engage in rehabilitation.

Addressing these concerns requires empathy and reassurance. Prosthetics should be framed as tools for comfort, safety, and dignity rather than symbols of loss. Frailty-based discussions help normalize limitations and focus on quality of life. When patients feel socially supported, they are more likely to use their devices consistently and safely.

Cost plays a significant role in prosthetic decisions, especially for elderly patients on fixed incomes. Advanced devices may promise greater function but come with higher costs for purchase, maintenance, and repairs. For frail patients, these investments may not translate into proportional benefits. Ethical care involves guiding families toward options that offer the best value in terms of safety and daily usability.

Frailty-based selection supports cost-effective decision-making. By matching device complexity to actual capacity, unnecessary expenses are avoided. This approach reduces financial stress and ensures that resources are used where they provide real benefit. Practical choices often lead to better long-term satisfaction and continued use.

Rehabilitation for geriatric prosthetic users must be highly individualized. Frailty levels determine not only what goals are appropriate but also how quickly progress can occur. For some patients, the primary goal may be safe transfers and short indoor walking. For others, limited outdoor mobility may be achievable. Setting goals that align with frailty prevents discouragement and reduces injury risk.

Clear, measurable goals help patients track progress and stay motivated. These goals should focus on daily activities that matter most to the patient, such as moving around the home or visiting nearby places. When rehabilitation feels relevant, engagement improves. Frailty-based planning ensures that goals remain realistic and meaningful.

Successful geriatric prosthetic rehabilitation often requires a multidisciplinary approach. Physiotherapists, prosthetists, physicians, and caregivers each contribute unique insights. Frailty assessment benefits from this collaboration, as different professionals observe different aspects of function and risk. Together, they can create a cohesive plan that addresses physical, cognitive, and emotional needs.

Regular communication among team members helps identify emerging issues early. Changes in health status, fatigue, or confidence can be addressed promptly. This coordinated approach reduces complications and supports sustained prosthetic use. Frailty-based teamwork enhances safety and outcomes.

Frailty is not static, and rehabilitation plans must adapt accordingly. Illness, hospitalization, or aging-related decline can alter capacity suddenly. Training intensity and goals may need adjustment to maintain safety. Recognizing when to slow down or modify exercises is a sign of good care, not failure.

Ongoing reassessment ensures that the prosthetic continues to serve the patient effectively. Sometimes this means reducing usage expectations or shifting focus to comfort and stability. Flexibility in rehabilitation planning supports long-term well-being and preserves independence where possible.

In geriatric prosthetics, success should not be measured solely by walking distance or speed. Frail patients often value safety, comfort, and confidence more than performance metrics. Being able to move without fear, participate in family life, or manage daily tasks independently can represent significant achievements.

Quality of life measures provide a more accurate picture of prosthetic success. Reduced caregiver burden, fewer falls, and improved mood are meaningful outcomes. Frailty-based selection aligns prosthetic goals with these broader measures, leading to more satisfying results for patients and families.

Falls, skin breakdown, and overuse injuries are common complications in frail prosthetic users. These issues can lead to hospitalization, further decline, and loss of independence. Careful device selection and training reduce these risks significantly. Frailty-based planning emphasizes prevention rather than reaction.

Regular follow-up and early intervention are critical. Small discomforts or balance issues should be addressed before they escalate. By prioritizing safety and comfort, prosthetic care can help keep elderly patients healthier and more independent for longer.

Prosthetic use can restore a sense of control after limb loss, especially for elderly patients who fear dependency. When devices are well-matched to frailty, users feel more confident and less anxious. This emotional benefit often extends beyond mobility, improving overall outlook and engagement with life.

Conversely, poorly matched prosthetics can increase frustration and helplessness. Frailty-based selection protects emotional well-being by setting patients up for success rather than repeated struggle. A positive experience fosters trust in care providers and encourages continued participation in rehabilitation.

As awareness grows, frailty assessment is becoming an essential part of geriatric care. Integrating it formally into prosthetic evaluation processes can standardize safer decision-making. Simple screening tools and functional tests can provide valuable insights without adding significant burden to clinics.

Wider adoption of frailty-based criteria will improve consistency and outcomes across settings. It encourages clinicians to look beyond age and diagnosis, focusing instead on functional reality. This shift represents an important step toward more humane and effective prosthetic care for the elderly.

Future prosthetic designs must increasingly consider the needs of frail users. Lightweight materials, intuitive controls, and enhanced stability features can improve safety and usability. Designs that prioritize comfort and ease of use over complexity will better serve geriatric populations.

Collaboration between manufacturers, clinicians, and patients is key to meaningful innovation. Feedback from elderly users provides valuable insights into real-world challenges. Frailty-based design thinking ensures that technology evolves in ways that truly benefit those who need it most.

Educating caregivers and families about frailty and prosthetic selection is essential for sustainable success. When support networks understand the reasoning behind device choices and limitations, they are better equipped to assist safely. Awareness reduces unrealistic expectations and fosters cooperation during rehabilitation.

Accessible educational resources can empower families to make informed decisions. This shared understanding strengthens the care environment and enhances patient outcomes. Frailty-based education supports a more compassionate and effective approach to geriatric prosthetic care.

Real-world cases often reveal more than theory. In geriatric prosthetic care, success stories usually share common traits rather than dramatic outcomes. One such pattern is careful matching of prosthetic demands to the patient’s frailty level. Patients who succeed are not always the strongest or healthiest, but they are those whose devices fit seamlessly into their daily routines without overwhelming their bodies or minds.

Successful elderly users often start with very modest goals. They may aim to stand safely, walk short distances indoors, or move confidently within familiar spaces. Over time, these small wins build confidence and routine. The prosthetic becomes a support rather than a challenge. Frailty-based selection makes these outcomes more likely by reducing early failure and fear.

Another key factor is patience during training. Elderly patients who are allowed to progress at their own pace show better long-term use. When clinicians resist the urge to accelerate milestones, patients feel respected and secure. This emotional safety is just as important as physical readiness in sustaining prosthetic use.

Prosthetic abandonment among geriatric patients is often misunderstood. It is rarely due to lack of effort or will. More commonly, abandonment reflects a mismatch between device demands and the patient’s frailty. When a prosthetic causes repeated fatigue, pain, or fear, patients naturally withdraw from using it.

Common reasons include excessive weight of the device, complicated donning procedures, or unstable movement patterns. Cognitive overload during walking is another frequent issue. Frail patients may feel mentally exhausted after short use, leading them to avoid the prosthetic altogether. These outcomes highlight the importance of simplicity and predictability in design.

Abandonment also occurs when expectations are unrealistic. If patients believe the prosthetic will restore abilities they had decades ago, disappointment is inevitable. Frailty-based counseling helps align expectations with reality, reducing emotional distress and improving acceptance. Understanding why abandonment happens allows clinicians to prevent it through better initial decisions.

Each geriatric prosthetic case adds to collective knowledge. Patterns observed across patients can guide future decisions. Frailty-based insights help clinicians refine assessment methods, improve communication, and select more appropriate devices. Over time, this leads to higher overall success rates and fewer adverse events.

Documenting outcomes and sharing experiences within care teams is valuable. It helps identify which approaches work best for different frailty profiles. Continuous learning ensures that prosthetic care evolves alongside patient needs. This reflective practice is essential for improving geriatric outcomes.

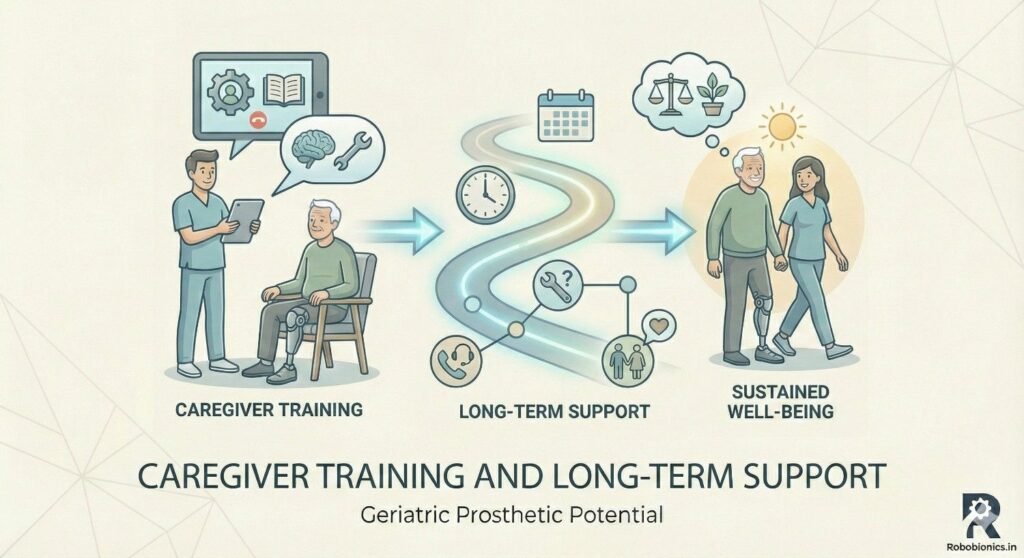

Caregivers play a vital role in the daily use of prosthetics by frail elderly patients. Without proper training, even well-intentioned assistance can increase risk. Teaching caregivers how to support balance, assist with transfers, and respond to near-falls is essential for safety.

Training should focus on practical scenarios that occur at home. This includes helping the patient stand up, navigate tight spaces, or manage uneven surfaces. Clear guidance reduces anxiety for both patient and caregiver. When caregivers feel confident, patients are more willing to use their prosthetics regularly.

It is also important to teach caregivers when not to intervene. Over-assistance can reduce patient confidence and independence. Frailty-based guidance helps caregivers strike the right balance between support and autonomy. This balance fosters safer and more sustainable prosthetic use.

Daily routines around prosthetic use can be challenging for frail patients. Tasks such as donning, doffing, cleaning, and skin inspection require time and attention. Caregivers often assist with these activities, especially when dexterity or vision is limited.

Simplifying routines reduces daily burden. Prosthetic designs that are easy to put on and remove save energy and reduce frustration. Caregivers should be trained to check for skin irritation and fit issues regularly. Early detection of problems prevents discomfort and more serious complications.

Establishing consistent routines helps integrate the prosthetic into daily life. When use becomes predictable, patients feel more in control. Frailty-based planning ensures that routines remain manageable rather than exhausting.

Beyond physical assistance, caregivers provide crucial emotional support. Frail elderly patients may feel discouraged during slow progress or setbacks. Gentle encouragement and reassurance help maintain motivation. Caregivers who understand frailty are better equipped to offer appropriate support without pressure.

Open communication between caregivers and clinicians is important. Sharing observations about fatigue, mood, or confidence helps adjust care plans. Emotional well-being directly affects prosthetic use and overall quality of life. Supportive caregiving strengthens outcomes across all dimensions.

Advanced prosthetic components such as microprocessor-controlled joints or dynamic feet offer benefits for certain users. However, for frail geriatric patients, these features may introduce complexity that outweighs advantages. Increased weight, maintenance needs, and learning demands can become barriers rather than aids.

Frailty-based evaluation helps determine whether advanced components are appropriate. In many cases, stability and predictability are more valuable than responsiveness. Simple mechanical systems often provide safer and more consistent performance for elderly users. Technology should serve the patient, not challenge them.

When advanced components are considered, thorough trials are essential. Observing how patients respond over time provides insight into real-world suitability. Decisions should be revisited regularly as frailty levels change.

Reliability is critical for geriatric prosthetic users. Frail patients may not cope well with device malfunctions or frequent servicing needs. Breakdowns can disrupt routines and reduce confidence. Inconsistent performance may also increase fall risk.

Prosthetics chosen for elderly patients should prioritize durability and ease of maintenance. Local service availability is an important factor. Devices that require minimal adjustments are often better suited for frail users. This practical approach supports uninterrupted daily use.

Clear instructions for troubleshooting simple issues can empower caregivers. Knowing how to respond to minor problems reduces panic and dependence. Reliability builds trust in the device and encourages continued use.

Some advanced prosthetics provide sensory feedback or adaptive responses. While beneficial for certain populations, these features can overwhelm frail elderly users. Excessive sensory input may increase confusion or anxiety during movement.

Frailty-based selection emphasizes calm and predictable interactions. Devices should behave consistently across environments. Sudden changes in resistance or movement can startle users and disrupt balance. Simplicity enhances safety and confidence.

Designers and clinicians must consider sensory tolerance when prescribing technology. What seems helpful in theory may be counterproductive in practice. Careful evaluation ensures that prosthetics remain supportive rather than distracting.

As populations age, the need for geriatric prosthetic services will continue to grow. Ensuring access requires thoughtful policy planning and resource allocation. Frailty-based frameworks can guide efficient use of limited resources by targeting interventions where they are most beneficial.

Public health systems must recognize that elderly prosthetic users have different needs from younger populations. Funding models should support assessment, training, and follow-up rather than focusing solely on device provision. Comprehensive care improves outcomes and reduces long-term costs.

Community-based services can play an important role. Bringing care closer to patients reduces travel burden and improves follow-up adherence. Accessibility is a key determinant of success for frail elderly users.

Widespread adoption of frailty-based prosthetic care requires education and training. Clinicians must be equipped to assess frailty accurately and apply findings to device selection and rehabilitation planning. This knowledge should be integrated into professional education and ongoing training programs.

Standardized assessment tools can support consistency across settings. However, clinical judgment remains essential. Frailty-based care combines structured evaluation with individualized decision-making. Training programs should emphasize both aspects.

Building awareness among healthcare providers fosters more ethical and effective care. When frailty is understood and respected, patient outcomes improve. Education is a cornerstone of systemic change.

Frailty-based prosthetic selection has benefits beyond individual patients. By reducing falls, complications, and hospitalizations, it eases strain on healthcare systems. Preventive approaches are more cost-effective than reactive care.

Improved prosthetic adherence reduces wasted resources. Devices that are used consistently provide better value than those abandoned early. Frailty-based planning supports sustainable healthcare delivery in aging societies.

From a public health perspective, supporting safe mobility among elderly amputees promotes independence and social participation. These outcomes contribute to healthier aging and reduced caregiver burden.

As life expectancy rises, more individuals will live with advanced frailty. Prosthetic care must adapt to this reality. Devices and rehabilitation models designed for younger users may not translate effectively to older populations.

Frailty-based frameworks provide a roadmap for adaptation. They emphasize safety, comfort, and quality of life over performance metrics. This shift aligns prosthetic care with the realities of aging.

Anticipating future needs allows manufacturers and clinicians to innovate responsibly. Planning for frailty ensures that prosthetic solutions remain relevant and beneficial.

Home-based care models are increasingly important for frail elderly patients. Remote monitoring and virtual consultations can support ongoing assessment and adjustment. These approaches reduce travel demands and improve continuity of care.

Frailty-based monitoring focuses on functional changes rather than technical metrics alone. Observing daily activity patterns provides valuable insight into patient well-being. Technology can support this without overwhelming users.

Integrating home-based support strengthens long-term outcomes. It allows timely intervention and reinforces patient confidence. Care models must remain flexible and responsive to frailty-related changes.

Despite technological advances, the human element remains central to geriatric prosthetic success. Empathy, patience, and communication are essential qualities in care providers. Frail elderly patients benefit most from relationships built on trust and understanding.

Frailty-based care reinforces this human-centered approach. It encourages clinicians to see patients as individuals with unique histories, values, and limits. This perspective enhances ethical decision-making and patient satisfaction.

As prosthetic care evolves, maintaining this focus will be crucial. Technology should support, not replace, human connection. The future of geriatric prosthetics depends on balancing innovation with compassion.

Frailty-based prosthetic selection should always begin with understanding the patient’s daily life. This means looking closely at where the patient lives, how they move through their day, and what activities truly matter to them. For many elderly patients, daily life revolves around a few key spaces such as the bedroom, bathroom, kitchen, and a small outdoor area. Prosthetic goals must fit into this reality rather than aiming for idealized mobility outcomes.

By starting with daily routines, clinicians can identify the minimum level of function required for meaningful independence. This approach avoids unnecessary complexity and reduces risk. It also helps patients feel heard, which improves cooperation and trust throughout the process. Frailty-based care is most effective when it reflects real life rather than clinical assumptions.

Frailty is multi-dimensional and cannot be understood through physical strength alone. A complete assessment must include endurance, balance, cognition, emotional resilience, and recovery capacity. These elements interact constantly. For example, mild physical weakness combined with anxiety can result in severe functional limitation during prosthetic use.

Clinicians should observe how patients respond to simple challenges over time rather than relying on single tests. Fatigue patterns, attention span, and emotional reactions provide valuable insight into reserve capacity. This holistic view helps predict how the patient will adapt to prosthetic demands in the real world. It also supports safer and more personalized device selection.

Once frailty is clearly understood, prosthetic demands must be carefully matched to that level. This includes weight, complexity, alignment sensitivity, and learning requirements. For patients with higher frailty, stability and predictability should be prioritized over responsiveness or speed. For those with moderate frailty, carefully selected features may be introduced with close monitoring.

This matching process should be collaborative and transparent. Patients and caregivers should understand why certain options are recommended and others avoided. When people see that decisions are made in their best interest rather than based on cost or technology trends, acceptance improves. Frailty-based matching is a protective strategy that supports long-term success.

Prosthetic success in geriatric patients depends heavily on training and follow-up. Frail patients require slower pacing, frequent rest, and repeated reinforcement. Planning these elements from the beginning prevents frustration and injury. Training should focus on safe movement patterns that align with daily needs rather than abstract exercises.

Follow-up must be regular and accessible. Changes in health, weight, or confidence can quickly affect prosthetic fit and safety. Early intervention prevents small issues from becoming major setbacks. A proactive follow-up plan reflects respect for the dynamic nature of frailty and aging.

Manufacturers play a critical role in supporting frailty-based prosthetic care. Designs intended for elderly users should emphasize light weight, stability, ease of use, and comfort. Controls and adjustments should be intuitive, with minimal steps required for daily handling. Devices should tolerate minor alignment changes without compromising safety.

Listening to feedback from geriatric users and clinicians is essential. Real-world insights reveal challenges that may not appear in laboratory testing. By designing with frailty in mind, manufacturers can create solutions that truly support elderly independence rather than unintentionally increasing burden.

Beyond product design, manufacturers can contribute through education and support. Clear training materials, caregiver guides, and maintenance instructions help ensure safe use. Educational initiatives focused on frailty awareness can improve prescription quality and outcomes.

Collaboration between manufacturers and care teams strengthens the entire prosthetic ecosystem. When everyone shares a common understanding of frailty-based principles, patient care becomes more consistent and effective. Education is a powerful tool for improving geriatric outcomes.

Innovation in prosthetics must be guided by responsibility, especially when serving frail elderly populations. Not every technological advancement is appropriate for every user. Ethical innovation focuses on meaningful benefit rather than novelty. It prioritizes safety, dignity, and long-term usability.

Manufacturers who embrace frailty-based thinking contribute to more sustainable and humane healthcare. This approach builds trust with clinicians, patients, and families. Responsible innovation ensures that progress serves those who need it most.

Frailty-based selection criteria represent a shift in how success is defined in geriatric prosthetics. Success is no longer about maximum performance or advanced technology. It is about safety, comfort, confidence, and the ability to live daily life with dignity. For elderly patients, these outcomes matter far more than distance walked or speed achieved.

At Robobionics, our experience has shown that when frailty guides decision-making, outcomes improve across every dimension. Patients feel safer, caregivers feel more confident, and clinicians see fewer complications and abandonments. Most importantly, elderly individuals regain a sense of control and participation in their own lives.

As populations continue to age, frailty-based prosthetic care will become increasingly important. It offers a practical, ethical, and human-centered framework for supporting elderly amputees. By respecting the realities of aging and focusing on what truly matters, prosthetic care can make a meaningful difference in the lives of geriatric patients and those who support them.

For many clinicians, the surgery is only the first step. What happens after the operation

For trauma amputees, the journey does not begin at the prosthetic clinic. It begins much

Amputation after cancer is not just a surgical event. It is the end of one

When a child loses a limb, the challenge is never only physical. A child’s body

Last updated: November 10, 2022

Thank you for shopping at Robo Bionics.

If, for any reason, You are not completely satisfied with a purchase We invite You to review our policy on refunds and returns.

The following terms are applicable for any products that You purchased with Us.

The words of which the initial letter is capitalized have meanings defined under the following conditions. The following definitions shall have the same meaning regardless of whether they appear in singular or in plural.

For the purposes of this Return and Refund Policy:

Company (referred to as either “the Company”, “Robo Bionics”, “We”, “Us” or “Our” in this Agreement) refers to Bionic Hope Private Limited, Pearl Haven, 1st Floor Kumbharwada, Manickpur Near St. Michael’s Church Vasai Road West, Palghar Maharashtra 401202.

Goods refer to the items offered for sale on the Website.

Orders mean a request by You to purchase Goods from Us.

Service refers to the Services Provided like Online Demo and Live Demo.

Website refers to Robo Bionics, accessible from https://robobionics.in

You means the individual accessing or using the Service, or the company, or other legal entity on behalf of which such individual is accessing or using the Service, as applicable.

You are entitled to cancel Your Service Bookings within 7 days without giving any reason for doing so, before completion of Delivery.

The deadline for cancelling a Service Booking is 7 days from the date on which You received the Confirmation of Service.

In order to exercise Your right of cancellation, You must inform Us of your decision by means of a clear statement. You can inform us of your decision by:

We will reimburse You no later than 7 days from the day on which We receive your request for cancellation, if above criteria is met. We will use the same means of payment as You used for the Service Booking, and You will not incur any fees for such reimbursement.

Please note in case you miss a Service Booking or Re-schedule the same we shall only entertain the request once.

In order for the Goods to be eligible for a return, please make sure that:

The following Goods cannot be returned:

We reserve the right to refuse returns of any merchandise that does not meet the above return conditions in our sole discretion.

Only regular priced Goods may be refunded by 50%. Unfortunately, Goods on sale cannot be refunded. This exclusion may not apply to You if it is not permitted by applicable law.

You are responsible for the cost and risk of returning the Goods to Us. You should send the Goods at the following:

We cannot be held responsible for Goods damaged or lost in return shipment. Therefore, We recommend an insured and trackable courier service. We are unable to issue a refund without actual receipt of the Goods or proof of received return delivery.

If you have any questions about our Returns and Refunds Policy, please contact us:

Last Updated on: 1st Jan 2021

These Terms and Conditions (“Terms”) govern Your access to and use of the website, platforms, applications, products and services (ively, the “Services”) offered by Robo Bionics® (a registered trademark of Bionic Hope Private Limited, also used as a trade name), a company incorporated under the Companies Act, 2013, having its Corporate office at Pearl Heaven Bungalow, 1st Floor, Manickpur, Kumbharwada, Vasai Road (West), Palghar – 401202, Maharashtra, India (“Company”, “We”, “Us” or “Our”). By accessing or using the Services, You (each a “User”) agree to be bound by these Terms and all applicable laws and regulations. If You do not agree with any part of these Terms, You must immediately discontinue use of the Services.

1.1 “Individual Consumer” means a natural person aged eighteen (18) years or above who registers to use Our products or Services following evaluation and prescription by a Rehabilitation Council of India (“RCI”)–registered Prosthetist.

1.2 “Entity Consumer” means a corporate organisation, nonprofit entity, CSR sponsor or other registered organisation that sponsors one or more Individual Consumers to use Our products or Services.

1.3 “Clinic” means an RCI-registered Prosthetics and Orthotics centre or Prosthetist that purchases products and Services from Us for fitment to Individual Consumers.

1.4 “Platform” means RehabConnect™, Our online marketplace by which Individual or Entity Consumers connect with Clinics in their chosen locations.

1.5 “Products” means Grippy® Bionic Hand, Grippy® Mech, BrawnBand™, WeightBand™, consumables, accessories and related hardware.

1.6 “Apps” means Our clinician-facing and end-user software applications supporting Product use and data collection.

1.7 “Impact Dashboard™” means the analytics interface provided to CSR, NGO, corporate and hospital sponsors.

1.8 “Services” includes all Products, Apps, the Platform and the Impact Dashboard.

2.1 Individual Consumers must be at least eighteen (18) years old and undergo evaluation and prescription by an RCI-registered Prosthetist prior to purchase or use of any Products or Services.

2.2 Entity Consumers must be duly registered under the laws of India and may sponsor one or more Individual Consumers.

2.3 Clinics must maintain valid RCI registration and comply with all applicable clinical and professional standards.

3.1 Robo Bionics acts solely as an intermediary connecting Users with Clinics via the Platform. We do not endorse or guarantee the quality, legality or outcomes of services rendered by any Clinic. Each Clinic is solely responsible for its professional services and compliance with applicable laws and regulations.

4.1 All content, trademarks, logos, designs and software on Our website, Apps and Platform are the exclusive property of Bionic Hope Private Limited or its licensors.

4.2 Subject to these Terms, We grant You a limited, non-exclusive, non-transferable, revocable license to use the Services for personal, non-commercial purposes.

4.3 You may not reproduce, modify, distribute, decompile, reverse engineer or create derivative works of any portion of the Services without Our prior written consent.

5.1 Limited Warranty. We warrant that Products will be free from workmanship defects under normal use as follows:

(a) Grippy™ Bionic Hand, BrawnBand® and WeightBand®: one (1) year from date of purchase, covering manufacturing defects only.

(b) Chargers and batteries: six (6) months from date of purchase.

(c) Grippy Mech™: three (3) months from date of purchase.

(d) Consumables (e.g., gloves, carry bags): no warranty.

5.2 Custom Sockets. Sockets fabricated by Clinics are covered only by the Clinic’s optional warranty and subject to physiological changes (e.g., stump volume, muscle sensitivity).

5.3 Exclusions. Warranty does not apply to damage caused by misuse, user negligence, unauthorised repairs, Acts of God, or failure to follow the Instruction Manual.

5.4 Claims. To claim warranty, You must register the Product online, provide proof of purchase, and follow the procedures set out in the Warranty Card.

5.5 Disclaimer. To the maximum extent permitted by law, all other warranties, express or implied, including merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, are disclaimed.

6.1 We collect personal contact details, physiological evaluation data, body measurements, sensor calibration values, device usage statistics and warranty information (“User Data”).

6.2 User Data is stored on secure servers of our third-party service providers and transmitted via encrypted APIs.

6.3 By using the Services, You consent to collection, storage, processing and transfer of User Data within Our internal ecosystem and to third-party service providers for analytics, R&D and support.

6.4 We implement reasonable security measures and comply with the Information Technology Act, 2000, and Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

6.5 A separate Privacy Policy sets out detailed information on data processing, user rights, grievance redressal and cross-border transfers, which forms part of these Terms.

7.1 Pursuant to the Information Technology Rules, 2021, We have given the Charge of Grievance Officer to our QC Head:

- Address: Grievance Officer

- Email: support@robobionics.in

- Phone: +91-8668372127

7.2 All support tickets and grievances must be submitted exclusively via the Robo Bionics Customer Support portal at https://robobionics.freshdesk.com/.

7.3 We will acknowledge receipt of your ticket within twenty-four (24) working hours and endeavour to resolve or provide a substantive response within seventy-two (72) working hours, excluding weekends and public holidays.

8.1 Pricing. Product and Service pricing is as per quotations or purchase orders agreed in writing.

8.2 Payment. We offer (a) 100% advance payment with possible incentives or (b) stage-wise payment plans without incentives.

8.3 Refunds. No refunds, except pro-rata adjustment where an Individual Consumer is medically unfit to proceed or elects to withdraw mid-stage, in which case unused stage fees apply.

9.1 Users must follow instructions provided by RCI-registered professionals and the User Manual.

9.2 Users and Entity Consumers shall indemnify and hold Us harmless from all liabilities, claims, damages and expenses arising from misuse of the Products, failure to follow professional guidance, or violation of these Terms.

10.1 To the extent permitted by law, Our total liability for any claim arising out of or in connection with these Terms or the Services shall not exceed the aggregate amount paid by You to Us in the twelve (12) months preceding the claim.

10.2 We shall not be liable for any indirect, incidental, consequential or punitive damages, including loss of profit, data or goodwill.

11.1 Our Products are classified as “Rehabilitation Aids,” not medical devices for diagnostic purposes.

11.2 Manufactured under ISO 13485:2016 quality management and tested for electrical safety under IEC 60601-1 and IEC 60601-1-2.

11.3 Products shall only be used under prescription and supervision of RCI-registered Prosthetists, Physiotherapists or Occupational Therapists.

We do not host third-party content or hardware. Any third-party services integrated with Our Apps are subject to their own terms and privacy policies.

13.1 All intellectual property rights in the Services and User Data remain with Us or our licensors.

13.2 Users grant Us a perpetual, irrevocable, royalty-free licence to use anonymised usage data for analytics, product improvement and marketing.

14.1 We may amend these Terms at any time. Material changes shall be notified to registered Users at least thirty (30) days prior to the effective date, via email and website notice.

14.2 Continued use of the Services after the effective date constitutes acceptance of the revised Terms.

Neither party shall be liable for delay or failure to perform any obligation under these Terms due to causes beyond its reasonable control, including Acts of God, pandemics, strikes, war, terrorism or government regulations.

16.1 All disputes shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

16.2 A sole arbitrator shall be appointed by Bionic Hope Private Limited or, failing agreement within thirty (30) days, by the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration.

16.3 Seat of arbitration: Mumbai, India.

16.4 Governing law: Laws of India.

16.5 Courts at Mumbai have exclusive jurisdiction over any proceedings to enforce an arbitral award.

17.1 Severability. If any provision is held invalid or unenforceable, the remainder shall remain in full force.

17.2 Waiver. No waiver of any breach shall constitute a waiver of any subsequent breach of the same or any other provision.

17.3 Assignment. You may not assign your rights or obligations without Our prior written consent.

By accessing or using the Products and/or Services of Bionic Hope Private Limited, You acknowledge that You have read, understood and agree to be bound by these Terms and Conditions.